(In many places) Public improvement districts ought to be created as part of transit station development process: the east side of NoMA station as an example

There are all kinds of "special service districts" that collect taxes to fund certain types of programs, from water systems to roads and sidewalks. I've advocated for what I call "Transportation Renewal Districts" or TRDs, as a transit focused version of an "Urban Renewal District."

Along the Yellow Line, TriMet’s joint development program in Portland, OR, helped build the Patton Apartments (above) on land once occupied by the dilapitated Crown Motel. Photo via SERA Architects.

Portland, Oregon sort of does that, although they are still called "Urban Renewal Districts," as the creation of an URD allowed them to sell bonds against the anticipated rise in property tax revenues, as a way to generate funds to pay for the construction of the Yellow Line light rail.

In Texas, they call these districts "Public Improvement Districts," which function as business improvement districts but unlike BIDs in cities like DC, Philadelphia, or New York City, where the focus is on managing and marketing, these districts are used as vehicles to fund significant infrastructure development. (Similarly, Colorado has an add on sales tax called a public improvement fee, "Public improvement fees as sales tax add-ons") but the revenue streams are much lower than from property tax assessments.)

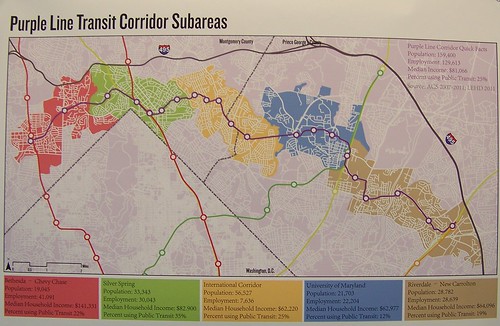

With the Purple Line, I suggested that Montgomery and Prince George's County should create a TRD covering the catchment area of the entire line, and create a development corporation to facilitate the development of areas around the station, and to fund other physical and placemaking improvements in association with the creation of that transit line, to reap benefits much faster than the more traditional "trickle down" approach that typifies the process.

-- "To build the Purple Line, perhaps Montgomery and Prince George's Counties will have to create a "Transportation Renewal District" and Development Authority," 2015

-- "Purple line planning in suburban Maryland as an opportunity to integrate place and people focused initiatives into delivery of new transit systems," 2014

-- "Quick follow up to the Purple Line piece about creating a Transportation Renewal District and selling bonds to fund equitable development," 2014

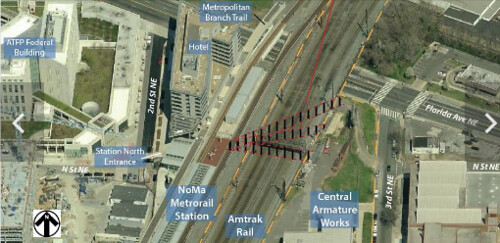

As mentioned in the previous piece, a special taxing district was created to raise money to pay for the creation of the NoMA Metrorail station (Project Profile: NoMA-Gallaudet University Metro Station, Innovative Project Delivery, Federal Highway Administration).

But the tax district was created very narrowly, with one purpose, to pay for the building of the Metrorail station. And they figured that improvements should only be paid for by the property owners on the west side of the station, because that's where the development impact was expected to occur.

But they didn't think about other improvements that might be needed in the district overall and how to pay for them. They didn't think about the eastern side of the station and the development impact and the possible need to expand the tax district to fund related needs ("The Development Wave on NoMa's East Side," Washingtonian Magazine).

Baring the failure to create a broader improvement-assessment district, the city doesn't make it easy to modify such districts. And there is a vision failure too. No one is talking about the need to modify the assessment district as a way to further extend the benefits of the station.

Photo: Dallas Morning News.

A counter example in Dallas is how PIDs can overlap. For example the new Klyde Warren Deck Park PID--the park was constructed over the Woodall Rodgers Freeway--overlaps with the Dallas Arts District and Uptown PIDs ("One year after heated dispute, Klyde Warren Park and Arts District officials partner to expand improvement district," DMN). They share some management. (Interestingly, an attempt to create a similar district to support the High Line Park in Manhattan did not succeed.)

Besides the parks issue, there are at least two examples of necessary transportation access infrastructure improvements on the eastern side of the NoMA station that are expensive and there is no funding to build them.

NoMA eastern pedestrian tunnel. Washington Business Journal reports ("Huge NoMa project replaces 'insular' site with 'true mixed-use'") that the Central Armature Works site will be redeveloped. It backs up to the tracks on the east side of the station, on 3rd Street NE. From the article:

According to a planned-unit development application filed Tuesday with the D.C. Zoning Commission, High Street will develop a 200-key hotel, two residential towers totaling 650 units (50 affordable), and 50,000 square feet of retail "on a site that was formerly dedicated to motor and apparatus repairs, installation and distribution." The triangular parcel, 760 feet in length, is currently home to a warehouse and surface parking lot. ...

The entire first level of the project, covering 96 percent of the lot, will contain a podium up to 22-feet high, according to the filings, a structure necessary to ensure each tower built above it will be exposed to daylight. Without it, the retaining wall between the property and the railroad tracks would block sunlight into the buildings.The developers are fine with providing access to an eastern entrance--really a pedestrian tunnel, and WMATA has been studying this independently ("A tunnel would improve Metro access for thousands in NoMa, but at what cost?," WBJ). But the cost is likely about $25 million and there aren't funds to pay for it. From the article:

In December, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, the District and consultant AECOM released a 182-page feasibility study for a NoMa pedestrian tunnel, covering everything from alignment and engineering to existing subsurface conditions, tunnel materials and potential cost. ...Just expand the assessment district!

The ridership at the NoMa-Gallaudet station has increased much faster than expected. In 2008, a WMATA capacity study predicted average weekday ridership would hit 3,919 boardings by 2030, an 80 percent increase over 25 years. Except that by 2014, ridership had already hit 8,412. And 81 percent of its users walk. ...

From the west side of the tracks, the walk (or bike ride) is relatively straightforward via N or M streets NE or the Metropolitan Branch Trail. From the east side, the hike can be a challenge, as pedestrians and cyclists must navigate heavy vehicular traffic, sidewalk gaps, narrow sidewalks and poorly lit underpasses. ...

The cost, per AECOM, is estimated to be between $16.6 million and $23.7 million, depending on the tunneling method and alignment used. The consultant recommended that the project be advanced to the preliminary engineering stage, “to analyze the complex and detailed engineering required to select a preferred alignment and tunneling method, and develop a biddable and constructible design that will bring this project to reality, improve access to the Metro station and serve as a catalyst for continued area growth.”

Given Metro’s declining ridership, safety crisis and financial doomsday predictions, the transit agency is not expected to invest much if anything in this project. A WMATA spokesman has not answered our questions about whether this is on their radar, and the project is not found in Metro’s capital improvement program.

Instead, if this tunnel is to happen, it will likely be funded via a joint effort of the NoMa Business Improvement District, the D.C. government and the private sector.

The BID, Dix said, is taking the lead on identifying funding sources.

“We anticipate that this will be a public-private partnership similar to the funding of the original station,” he said.

Create/Expand PIDs/TRDs for station catchment areas. A pedestrian tunnel for the east side of the Metro will benefit multiple developments located east of the tracks, not just the Central Armature site, including the Union Market District and Gallaudet University. It makes the whole area more accessible, which will be incredibly beneficial to DC, regardless of the support of continued ridership increases at that station.

Irrespective of WMATA's current troubles, while I argue in "Transit stations as an element of civic architecture/commerce as an engine of urbanism" and related pieces cited within that transit agencies need to address the place characteristics of stations as neighborhood gateways, the cost for doing shouldn't be seen as solely the responsibility of the transit agency.

Localities need to step up and provide additional funds to put in the kinds of place value enhancements that provide economic and placemaking returns.

PIDs/TRDs should be created as a matter of course to accomplish this, not just for the NoMA station but for most station catchment areas, depending on the access needs, development capacity, and the ability to generate new property tax revenues.

(Also see the example of Allentown, Pennsylvania in the past blog entry, "State-level initiatives to support center city revitalization in smaller towns." It's not a TRD but the funding process is comparable.)

Access to the New York Avenue and Florida Avenue bridges from the Metropolitan Branch Trail. The MBT is a bike and walking path connecting Union Station to Silver Spring in Montgomery County, parallel to the rail line.

While the trail was conceived primarily as a long distance bikeway between Silver Spring and Union Station, in the area south of Rhode Island Avenue, it is also becoming a "protected" way for residents--mostly on foot--to cross New York and Florida Avenues to get to NoMA, Union Station, and even Downtown.

Separately, the NoMA Business Improvement District commissioned a study, Metropolitan Branch Trail Safety & Access Study, to study opportunities for improvement.

One of the proposals is for a bridge over the railyard to connect to the Union Market district ("A bridge from Eckington to Union Market? It could happen," GGW).

In my opinion that is a difficult project to pull off, not particularly attractive, and expensive.

Other proposals aim to address the significant grade and height difference between the trail and surface connections to New York Avenue and Florida Avenue.

The Washington Gateway development takes up the odd triangle between the MBT and the two avenues.

Part of it is developed and they have a stairway connection to New York Avenue to the rear, while the project fronts Florida Avenue at grade.

Additionally, they have an entrance to the MBT on the portion of the property that is not yet developed, and they plan to maintain access to the trail when the new buildings are constructed.

Public escalator in Commune 13, Medellín. AP photo by Luis Benavides.

Vertical transportation infrastructure as an alternative and an element of a city's mobility system. In cities like New York, vertical transportation infrastructure--elevators and escalators--is essential to mobility in tall buildings. It's discussed in the late 1960s study from RPA (Urban Design Manhattan) as a key element of the mobility system, which they defined as below ground, at ground, at the mezzanine level, and up and down within buildings.

Monaco has public elevators and escalators to provide an easier way to get up the steep hills on which the city is built, up from the waterfront ("Vertical infrastructure in Monaco, Pop Up City).

Hong Kong also has a similar system of public escalators, to provide better access up steep hills.

More recently, as a way to improve access in economically disadvantaged communities located on steep hillsides, Medellín has created a system of public escalators ("Medellín, Colombia offers an unlikely model for urban renaissance," Toronto Star) which were constructed in hilly areas to provide access and connection to areas of the city that because of topography took hours to travel to and from the main city.

In this particular case I recommend that public access elevators--elevators are preferred over stairs for ADA reasons--be installed within the final phase of the Washington Gateway project to provide access to the New York Avenue and Florida Avenue bridges.

These wouldn't be WMATA projects, but DC Department of Transportation projects. And they should be funded by an expanded PID/TRD.

Somehow there would have to be a public-private partnership to do this, and regular maintenance provided (probably contracted out by DDOT to the BID or the building).

Cool design as an important feature. From the standpoint of "vertical transportation infrastructure" that is an element of the public mobility system and an element of civic architecture, were such elevators to be constructed, aesthetically forward designs would be ideal.

The closest we have to public elevators are the elevators in the WMATA system. While most of the elevators in the legacy system can be somewhat dismal, it happens that the elevators in the NoMA station are pretty nice (but slow).

Aesthetically forward elevators could make a big difference in defining the value of this particular type of infrastructure as part of the public mobility network.

Underground and aboveground walkway systems as comparable examples. Other relevant examples of creating atypical pedestrian mobility networks and infrastructure include the underground passageway systems in Chicago and Toronto ("Hong Kong needs to create a formal and planned pedestrian mobility system," "Toronto's PATH wanderers need direction," Toronto Star) and the above-ground skyway systems in St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota.

What's important is planning for an integrated mobility system. In cities where topography is an issue, aerial trams, escalators, inclines, walkways, stairs, and elevators can be key elements of a complete mobility system focused on facilitating movement in what we might call the Walking-Transit City, using the sustainable mobility platform concept as the primary organizing principle.

What's important is planning for an integrated mobility system. In cities where topography is an issue, aerial trams, escalators, inclines, walkways, stairs, and elevators can be key elements of a complete mobility system focused on facilitating movement in what we might call the Walking-Transit City, using the sustainable mobility platform concept as the primary organizing principle.Labels: bicycle and pedestrian planning, civic architecture, special tax districts, transit and economic development, transportation infrastructure, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

3 Comments:

The process for expanding the streetcar tax district in Kansas City is now underway. An expanded district would fund extension of the line.

http://www.masstransitmag.com/news/12219180/streetcar-supporters-discuss-expansion-proposal

Building one of the exits at the infill Potomac Yard station in Alexandria was dropped because of cost. They didn't have a PID in place.

But as part of the investments to attract Amazon HQ2, an agreement to add the previously dropped entrance was included.

https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2020/03/23/potomac-yard-metro-will-have-covered-southwest.html?

There used to be a connection underground between the PATH Station "next to" Penn Station and Penn Station, via a passageway operated by the old Gimbels Departmenet Store.

It went out of business and was replaced by a different development, the Manhattan Mall.

The passageway became disused and there was a dispute between the mall owner and MTA over who owned it and was responsible for it. So it closed. Apparently, the passageway is owned by Vornado, and the passageway would connect to the mall's food court.

http://www.erictb.info/33passage.html

It's a shame with the addition of the Moynihan Station to the Penn Station complex that this passageway wasn't revived also.

https://nypost.com/2010/11/28/remembering-the-gimbels-tunnel/

Separately, a developer working on a project adjacent to Grand Central Station included a number of transit improvements as part of the public benefits element of the project.

It's the One Vanderbilt Avenue complex by SL Green.

https://www.stantec.com/en/news/2020/stantec-designed-one-vanderbilt-transit-opens

From the article:

nfrastructure improvements include a 14,000 square foot pedestrian plaza on Vanderbilt Avenue between Grand Central and One Vanderbilt. Inside the tower, a 4,000 square foot public transit hall and series of below-grade ADA-accessible concourses and corridors provide new and enhanced connections to the Metro-North Railroad, the shuttle to Times Square, and future access to the LIRR station as part of the East Side Access project. The new transit hall’s flow and high-end finishes of stone, tile, glass, and metals echo the distinctive interiors of Grand Central and its clearly organized, airy open spaces.

The long-shuttered passageway between Grand Central and the Socony-Mobil Building at 150 E. 42nd Street has also re-opened with the addition of two street-level subway entrances and a new entrance to the 42nd Street subway station on the southeast corner of 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue. Circulation space on the subway platforms and mezzanine has been increased by 37 percent, providing commuters more room to socially distance and allowing for increased capacity once transit use rebounds to pre-pandemic levels. Enhanced finishes, additional turnstiles and gates, new stairways, escalators, and an ADA-accessible elevator have been added to ease congestion and improve transfers and the overall transit experience in the third busiest station in the New York City subway system.

Post a Comment

<< Home