Tearing down center cities

Recently, I wrote about the allegedly great proposal by the treasurer of Genessee County in Michigan to assist declining cities in demolishing and refocusing on smaller parts which may be sustainable. See "Shrinking Cities."

Kaid Benfield of the Natural Resources Defense Council, has an incredibly authoritative and thorough response to this issue in the NRDC Switchboard blog, "They are stardust. They are golden. But are they right about “shrinking cities”?."

The entry reminds me that I wrote about this kind of idea a couple months ago, in response to some other blog entries out there about urban decline. They were good entries, but in my opinion, missed the most basic reason for urban decline--suburbanization and outmigration from the center city, which is sometimes called "sprawl."

Note about this, I had a conversation Sunday after a Community Forklift board meeting with a planner-colleague and he was talking about the sprawl in the far suburbs, places like Prince William and Loudoun County, Virginia, and how they didn't do anything.

I told him that the planners knew, in the late 1950s, but they were powerless to stop it. I found at a used bookstore, a Fairfax County land use report from 1962, called The Vanishing Land, all about leapfrog development and its pernicious impact on open space and farmlands. But they were powerless against the Growth Machine--especially developer-lawyers like Til Hazel.

This is from the April entry "(Housing) duplication and revitalization":

A couple of blog entries elsewhere, "Detroit and the Limits to Urban Decline" from Goodspeed Update about Detroit, and "Cincinnati: Agenda 360" from Urbanophile about Cincinnatti are good, discussing urban decline, but I think they miss perhaps the most basic point about center city decline.

Disinvestment in center cities resulted from outmigration to the suburbs.

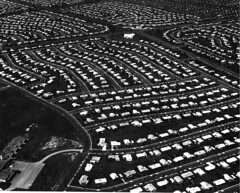

The development of massive tracts of suburban housing beginning in the 1950s created a large supply of new housing at the expense of extant housing, housing that was mostly located in the center cities. This would be called "oversupply." (This is discussed more succintly in Understanding Neighborhood Change: the role of expectations in urban revitalization by Rolf Goetze, published in 1979.) As a result of the oversupply, the value of extant housing was reduced significantly.

As of 2006, this bungalow in Detroit was valued at $59,450. It is roughly equivalent to "my" bungalow in Washington, DC, which cost $370,000 (and is less than one mile to the Metro, has a 90 foot long backyard, a full basement, and an attic that can be finished). The Detroit bungalow has 4 bedrooms (we have two), 1 bathroom, and a two-car garage. (We have a garage too, but it is termite infested.) From the USA Today article "Detroit: Thousands of homes swamp the market."

This image of a stripped, abandoned bungalow in Detroit comes from Zillow and this article, "The Remains of the $1 Detroit House." That's what happens when housing oversupply is created at the expense of the center city.

Levitttown, Pennsylvania. Photo source unknown.

As population declined in the city, property and sales tax revenues declined. This trend accelerated as industry and retail, for a variety of reasons, began to locate in the suburbs as well.

In areas where metropolitan population growth was relatively stagnant, this means for the most part that it is very difficult for the center city to "revitalize," because in a relatively weak market, it is hard to build demand for center city housing, especially if major businesses continue to decamp to suburban locations and without a high quality fixed rail transit system able to add significant value and demand back to urban neighborhoods.

Revitalization can occur but it has to happen on a district by district basis. You can't improve the whole city, at best you must "triage" and work to improve the neighborhoods (and the downtown) with the most potential, more of the characteristics that people want when choosing a neighborhood in which to buy a house.

(One of the problems with Cleveland's fixed rail transit system is that it isn't a complete system, and the newest line, the Airport Line constructed in the 1970s, abuts neighborhoods more than it serves neighborhoods. This resulted from the use of extant railroad lines rather than the creation of a new neighborhood-centric system. Cleveland's metropolitan population has not grown over the period from 1960-2000, hence the city's continued spiral downward, despite attractive neighborhoods and other assets.)

From 1960 to 2000, the population in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties in Michigan (Detroit is located in Wayne County) grew by only 200,000 people. (Although the metropolitan area did expand somewhat to include parts of Livingston, Washtenaw, Genessee, and Monroe Counties.) This meant that 1.1 million people moved out of Detroit, leaving their housing behind. And all that "deaccessioned" housing crumbled.

Similarly, the Cincinnati metropolitan area grew by only about 350,000 people from 1960 to 2000. Without significant growth in the region, the stage was never really set for urban revitalization. (Cincy also has some issues I think with a more urban renewal like focus, rather than an assets based approach typical of historic preservation based methods. See Cities Back from the Edge by Gratz for more on this general approach.)

The Washington region is significantly different from either of these areas. In 1960, the population of the region was about 2.1 million (defined as DC plus the inner counties and cities in Northern Virginia--Fairfax, Arlington and Alexandria, but not Prince William or Loudoun Counties, and PG and Montgomery Counties in Maryland). In 2000, the population of this same area was 3,566,275.

At the same time, the broader metropolitan region has expanded to include many additional counties in Maryland (e.g., parts of Howard, Frederick, and Anne Arundel Counties) and Virginia, and even Baltimore, according to the definition of the region by the US Census -- the combined SMSA had 7.5 million residents in 2000.

Sure DC continues to shrink in relationship to the region's entire population, but because the region continues to grow, housing stock in the city is no longer redundant, unlike weak market regions like Detroit, Cincinnati, Cleveland, or Pittsburgh (etc.). Therefore, DC is able to compete, based on the values of place--location and livability--for new residents.

It wasn't always so. The addition of the subway system, which at the current time favors the city with 29 stations at the core of the city, and 11 more stations in other locations in the city + two on the border, shared with other jurisdictions, made many neighborhoods locationally attractive.

Combine that with quality historic building stock, and in some neighborhoods, functioning commercial districts and quality schools (not enough local schools are quality, which has led to the charter school movement as well as the current operation to "fix" the schools), as well as improving municipal management, which started under Mayor Williams, and moves forward in fits and starts (for a comparison to Philadelphia, see this op-ed from the Philadelphia Daily News that I wrote in 2003, "An outsider's vision for saving Philly.")

Compare Baltimore and DC and you see the difference that having a good fixed rail transit system makes in terms of making inner city neighborhoods more attractive to people with choices. On the other hand, DC has another advantage that Baltimore will never have, the main employment engine--the federal government--is not going to leave the city. Meanwhile, major corporations continue to leave Baltimore. That being said, the Baltimore region continues to grow, and Baltimore is with 45 minutes commuting distance to DC (although commuting stinks) so it still has great potential, if it can get it together in terms of better urban transit.

Labels: building a local economy, housing market, urban history, urban renewal, urban revitalization, urban vs. suburban

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home