Thomas Circle is in the middle of this photograph, taken by Jason Hawkes for the Washington Convention and Tourism Corporation.

Thomas Circle is in the middle of this photograph, taken by Jason Hawkes for the Washington Convention and Tourism Corporation.Last week the National Trust for Historic Preservation's annual conference was held in DC.

But sadly it felt like DC as a node in the story of preservation policy and practice was a negligible piece of the conference agenda.

I expected that "pressing issues in 'preservation'" as reflected by present day DC experiences would have been central to the meeting's agenda.

There is a lot to learn, positive and negative.

For example, while I lament that far more buildings are unprotected rather than protected, DC has arguably the strongest local historic preservation law in the US, where interested parties who are not owners can submit nominations for landmarking, and the city's regulatory body, the Historic Preservation Review Board, makes decisions, not recommendations--in other cities, final decisions are made by the legislative branch, and recommendations made on historic preservation grounds are often rejected in favor of other considerations.

Still, there are many gaps in the protections that exist. DC's laws are all or nothing. Where buildings are designated, the protections are extensive. But there are virtually no protections for buildings eligible for historic designation, but not designated.

For example, ensuring high quality architectural and urban design treatments on DC's "avenues and boulevards" and at entry points into the city, when those areas aren't historically designated is one such issue.

In my comments a couple years ago on the DC preservation plan, I recommended that we move to managing the city's urban design qualities as if the entire city were a heritage area, which would mean mandatory design review, regardless of whether or not a particular area, building or site were designated.

In my comments a couple years ago on the DC preservation plan, I recommended that we move to managing the city's urban design qualities as if the entire city were a heritage area, which would mean mandatory design review, regardless of whether or not a particular area, building or site were designated. I argue it's shifting from thinking of and regulating the built environment on a building by building basis and instead considering these questions more broadly in terms of the built environment on a larger scale, as a "cultural landscape."

This is an extension of arguments made by Stephen Semes ("The Bias Against Tradition," Wall Street Journal). His book, The Future of the Past: A Conservation Ethic for Architecture, Urbanism and Historic Preservation, argues in favor of classical design as a way to protect and strengthen the architectural character of existing places, when new design is frequently discordant and diminishes the strength of the built environment as an ensemble. From the article:

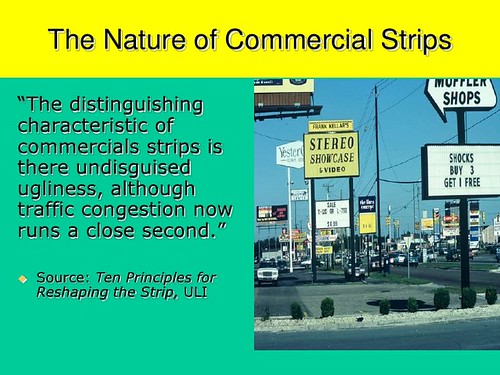

"Maintaining a broad stylistic consistency in traditional settings is not a matter of 'nostalgia,'" he says. "It's a matter of common sense, of reinforcing the sense of place that made a building or neighborhood special to begin with. But many academically trained preservationists want to impose their inevitably subjective notions of what the architecture 'of our time' is."Corridors. Thinking about aesthetic quality of streets as ensemble elements in urban design is not a new concept, although much of the work on the topic in the post-war era has been focused on suburban strips, the impact of sprawl, automobile-centric design, and a cacophony of signage, and has focused on commercial buildings. Ed McMahon, now of the Urban Land Institute, and others are known for their work in this area.

Slide from a presentation by Ed McMahon.

Yet, the corridor problem predates the widespread adoption of the automobile. Cities that had extensive streetcar systems, such as Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia (e.g., Germantown Avenue, Girard Avenue), Toronto, Washington, DC and others developed in a similar pattern, lined for miles by storefronts.

Today, these streets are difficult to improve, except at nodes, given fundamental changes in how people live, work, shop, and get around. Note that the recommendations in the Urban Land Institute report, Ten Principles for Reshaping America's Suburban Strips, are no less relevant to center cities.

In plans I produced for Cambridge, Maryland, Baltimore County, Maryland, and Brunswick, Georgia, recommendations were retained that called for special attention to the urban design qualities of corridors both for quality of life and placemaking reasons as well as because of how the built environment along the city's main streets and entryways shapes the identity of the community for residents and visitors.

DC created a "Great Streets" program with the intent of leveraging transportation infrastructure investments for broader revitalization improvements, in part based on the commercial district revitalization effort on H Street NE, which was built on a revitalization plan and targeted investments including transportation infrastructure and streetscape improvements.

Being one of the founders of the H Street initiative, I have written extensively about it ("The community development approach and the revitalization of DC's H Street corridor: congruent or oppositional approaches?" and pieces cited within) and commercial district revitalization ("The long term shake out of local retailers and independent commercial districts") more generally.

I argue that much of the reason for corridor decline in the urban renewal period ("The five periods of urban revitalization> since WWII") was the construction of new buildings with designs that rejected local identity and spirit of place. Instead of repairing the built environment and microeconomy of neighborhoods, the community development and urban renewal approach exacerbated the problems.

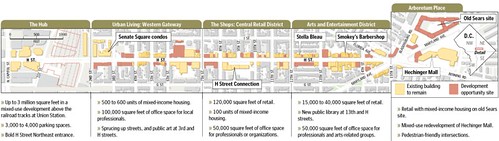

The 21st century revitalization program for H Street focused on adding population and suggested context-sensitive design for infill construction.

Washington Post graphic from the H Street Revitalization Plan produced in 2003.

It's been successful on H Street, but the program pre-existed the "Great Streets" initiative, and it has been difficult to reproduce H Street's success on other commercial corridors elsewhere in the city. Mostly, areas around transit stations and districts in the core of the city improve, while areas outside of the core or without transit stations continue to languish.

DC's Urban Design Element calls attention to the city's avenues but substantive actions have yet to be made. The Urban Design Element of DC's Comprehensive Land Use Plan discusses the importance of the city's avenues as defining features of the city and its identity. From the Urban Design Element:

Design decisions should reinforce the city’s pattern of axial, radial, and diagonal streets, and enhance the public spaces formed where these streets intersect one another. (p. 9-4)An entire policy section is devoted to "Reinforcing Boulevards and Gateways" but in the almost 10 years since the Comprehensive Plan was approved, necessary actions to put protections in place have not occurred. For example, there has been no movement on this recommendation:

UD-1.4 Reinforcing Boulevards and Gateways. Grand streets in the form of avenues and boulevards are another defining element of Washington’s urban form. The avenues originated as part of the L’Enfant design for the city. By overlapping a system of broad,

diagonal thoroughfares on a grid of lettered and numbered streets, streets like Pennsylvania Avenue were given immediate importance, creating memorable views and a strong sense of civic identity. Beyond the heart of the city, these avenues extend to the outer neighborhoods, in some cases forming dramatic points of entry into the District of Columbia. Over time, several other streets in the city grid were designed or redesigned to display similar characteristics. (p.9-12)

Action UD-1.4.A: Zoning and Views: As part of the revision of the District’s zoning regulations, determine the feasibility of overlays or special design controls that would apply to major boulevards and gateway streets. The purpose of such overlays would be to ensure the protection and enhancement of important views and to upgrade the aesthetic quality of key boulevards.If this recommendation had been actualized, it wouldn't be necessary to write this piece.

Apartment buildings as a type. Besides arguments in favor of treating avenues and streets as ensembles and signature elements of the city's built environment and identity, similarly we should consider the design of new individual apartment buildings in terms of the city's ouevre of apartment buildings, especially the body of work constructed before 1950..

It happens that DC has a wide range of distinctively designed apartment buildings, and four streets in particular--Connecticut Avenue, 16th Street, Wisconsin Avenue, and Massachusetts Avenue--are defined by this type, block after block, mile after mile.

Generally, the collection is harmonious, unified by the use of brick and stone but marked by a great variety of designs, shapes and sizes.

James Goode's Best Addresses is probably the most definitive work on DC's apartment buildings as a type. But what is lacking is a more full-blown thematic study of apartment buildings, treating apartment buildings as a thematic category within the nation's and city's built heritage. Unlike for "historic residential suburbs," I don't believe that the National Park Service has developed a thematic study on apartment buildings as a type.

With such a framework in place, it would be easier to justify setting higher standards and expectations for the construction of new apartment buildings, especially on an infill basis, in DC and other cities.

Belvedere Apartments, 13th Street and Massachusetts Avenue NW. Flickr photo by Josh.

Note that the book Utah's Historic Architecture Guide, published by that state's historic preservation office, has a very good sub-section on apartment buildings as a type, mostly focused on Salt Lake City. It's a good foundation for a deeper thematic study on apartment buildings.

The property owner specifically calls attention to the proposed architectural design in terms of the the site's centrality as a key entry point into the city. From the article:

The application refers to the site as a "gateway," as it touches the very northern edge of the District at its border with Silver Spring. According to the rezoning package, “the proposed building will effectively become a new landmark at the edge of the District.” The design, from Hickok Cole, features projecting bays, window wall glazing, brick and stone.Despite the assertions by the property owner, the design for the building at Eastern and Georgia Avenues isn't noteworthy, at least it isn't noteworthy from a positive standpoint.

The design of the building is pretty typical of the city's new apartment buildings. It's unmemorable, but not to the point of execrable. Average, banal, sure. If the developer is going to make claims about great architecture, then the results as currently projected should not go unchallenged.

Interestingly, while most of the buildings that will be demolished at the "Eastern Avenue Gateway" site lack heritage qualities, there is a subset that have been designed in a simple but attractive art deco style that if referenced, could yield a design that rises and projects gateway character.

This building at 2800 N. Milwaukee in Chicago's Logan Square presents much more gateway character and is an example of the kind of art deco design that could distinguish the DC site in question.

Also, art deco is one of the defining architectural styles of the Silver Spring conurbation in Montgomery County, the area of Montgomery County which immediately abuts this "gateway" to DC.

As a way of connecting the architectural heritage of the two districts, utilization of the art deco architectural style makes sense.

Designing the building in art deco style would be a much better contribution to the gateway aspect of the location, would be a respectful acknowledgement of the best designed buildings currently on the site, and if done properly would be an upgrade to the neighborhood, the Georgia Avenue corridor, and to its location on a major avenue and entryway into the City of Washington.

Note that the condominium building constructed by the same company at the intersection of 4th Street, H Street, and Massachusetts Avenue NW does project a design worthy of a gateway building.

The design responds to the triangular shape of the lot, its location on a prominent avenue and its position as an entry point to Downtown and the Central Business District and on major arteries into and out of the city.

400 Massachusetts Avenue NW. In a modern exception to the general "rule" of how triangularly shaped buildings tend to be designed the side elevations are accentuated with a wave form design and different colors of brick, rather than by a more background treatment.

Cafritz apartment building at 5333 Connecticut Avenue NW. The apartment building currently under construction in the Chevy Chase neighborhood of DC is another example of the need to have extraordinary design approval processes for architecturally significant avenues that do not enjoy historic district protections.

As a downtown or suburban office building this glass curtain-wall clad building would be unmemorable, sub-average but typical of the type.

As an apartment building it is an outlier because it is rare, at least in this region (Manhattan, Miami, and more recently London are exceptions) for apartment buildings to be clad fully in glass.

As a downtown or suburban office building this glass curtain-wall clad building would be unmemorable, sub-average but typical of the type.

As an apartment building it is an outlier because it is rare, at least in this region (Manhattan, Miami, and more recently London are exceptions) for apartment buildings to be clad fully in glass.

2126 Connecticut Ave. NW, the Dresden Apartments

Like many older US cities, DC has a signature collection of apartment buildings and Connecticut Avenue is one of the city's signature avenues, defined by brick and stone apartment buildings that stretch from Dupont Circle almost to the Maryland border.

Comparing the 5333 building to other apartment buildings on three different scales: (1) in the vicinity of the site; (2) along the entire length of Connecticut Avenue; and (3) in comparison to the city's collection of signature apartment buildings, I would argue it fails.

It challenges convention but the ordinariness of the design--extraordinary only because of its absolute discordance-- fails to support its challenge to a more conventional approach that is more appropriate to its location within the urban ensemble that is Connecticut Avenue and the Chevy Chase neighborhood.

Like many older US cities, DC has a signature collection of apartment buildings and Connecticut Avenue is one of the city's signature avenues, defined by brick and stone apartment buildings that stretch from Dupont Circle almost to the Maryland border.

Comparing the 5333 building to other apartment buildings on three different scales: (1) in the vicinity of the site; (2) along the entire length of Connecticut Avenue; and (3) in comparison to the city's collection of signature apartment buildings, I would argue it fails.

It challenges convention but the ordinariness of the design--extraordinary only because of its absolute discordance-- fails to support its challenge to a more conventional approach that is more appropriate to its location within the urban ensemble that is Connecticut Avenue and the Chevy Chase neighborhood.

2001 16th Street NW. By comparison to Manhattan, DC has lots of "Flatiron Buildings" because so many avenues cut lots at angles to the grid.

Over the decades this has resulted in a large number of buildings, commercial and residential, designed to accentuate the triangular shape of their lot.

This is a phenomenon not unique to DC.

Many cities, in the US such as New York City in Manhattan especially starting with the Flatiron Building and Chicago, and around the world, especially in Paris, have similar spatial conditions which have generated a large number of triangular shaped buildings, and a unique and attractive building type.

109 Prince Street (1882) at Prince and Green Streets. New York City, New York. Flickr photo by Dan Haneckow.

Madrid. Photographer unknown.

Logan Square area, Chicago.

Ornate or not, typically the design of such buildings focuses attention on and accentuates the apex, while treating the building's elevations more as a background element, attractive but secondary to the unique shape of the building.

Just as an argument can be made for the necessity of a thematic survey of apartment buildings, DC needs a thematic survey of triangle buildings.

And the place of this type of building needs to be maintained and utilized going forward when considering new projects, in terms of the architectural possibilities offered by odd shaped lots and the broader urban design and placemaking characteristics of the city's avenues and how their intersections create the potential for attractive and atypical architecture.

3701 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Petworth.

Another site on Georgia Avenue that raises "gateway" issues is the sliver of land between New Hampshire Ave. NW and Rock Creek Ford Road NW at the southeast corner of the intersection of Georgia and New Hampshire Avenues.

Proposed building.

This is a "gateway" site, but at a node within the city, rather than an entry point. It's a triangular site, currently occupied by a number of undistinguished liner buildings.

The Georgia-New Hampshire intersection is the location of the only Metrorail station on Georgia Avenue, and with the addition of new multiunit buildings, more population has sparked significant improvement of neighborhood retail and restaurant options. The commercial area around the station and on nearby Upshur Street is on the rise.

Compared to many buildings, the proposed apartment building for the site is attractively designed in that it acknowledges the red brick history in many of the city's apartment buildings.

But the design inadequately acknowledges the triangular nature of the lot, instead squaring off the building at the apex.

In the great tradition of DC's triangular buildings at avenue junctions, ideally the design would express the form of the lot in the shape of the building, focused at the apex, (Note that the rendering shown in an UrbanTurf article about the project, perhaps generated at an earlier point in the process, is even more attractive, but still de-emphasizes the triangle.)

Google Street View of the site.

1400 H Street NE/1401 Florida Avenue NE. Failing to acknowledge the principles of the best designed triangle-shaped buildings--delineating the apex with the building's elevations attractive but subservient to the point of the triangle--is the issue with the renderings for the new apartment building on a triangular lot on the 1400 block of H St. NE at Florida Avenue ("New gateway to H Street NE? Mixed-use building proposed for site next to Starburst intersection," Washington Business Journal).

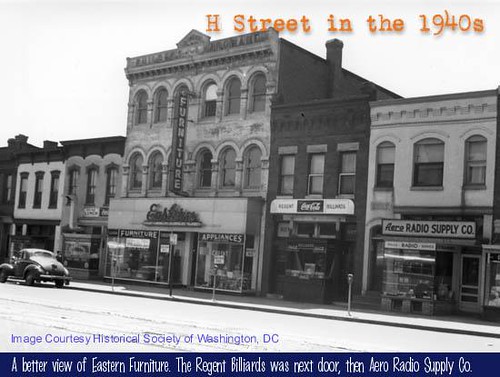

This site is at the eastern gateway to H Street NE, which historically was a major entry point into the city from Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City (also the road that British troops marched on in their sack of Washington during the War of 1812).

A gatehouse at the intersection of Bladensburg Road and Maryland Avenue, was where tolls were collected from people entering the city.

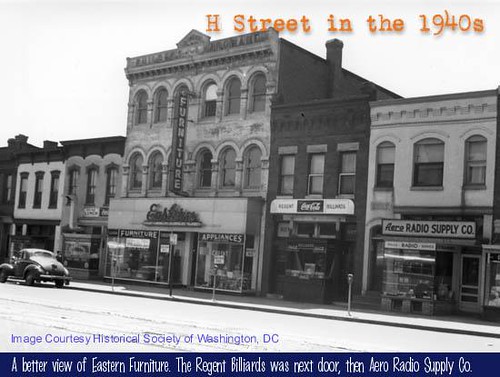

For decades, H Street was one of the city's most important commercial districts--one of the nation's first Sears Department Stores was built a short distance away on Bladensburg Road--but the corridor languished starting in the 1950s as residents decamped for the suburbs.

Riots after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. left scars on the corridor that remained for decades, but over the last 15 years the corridor has experienced significant revitalization, and will serve as the location for the city's first streetcar service.

Separately from projects around Union Station, as much as $1 billion in new construction has been built, is under construction, or planned for the corridor, since the revitalization plan for the corridor was released in 2003.

As a "gateway" building at a key entry point to an increasingly important and revived commercial corridor, there should be much greater attention to ensuring the production of a lasting architectural treatment for this site.

Note the triangular form of the site as shown in the image to the right.

Interestingly, this building and the project in Petworth share the same architectural firm, PGN Architects.

Compared to ouevre of historic triangularly-shaped buildings on many of the city's avenues, the design contravenes tradition by drawing attention to the side elevations rather than the apex.

But H Street is not designated historic and therefore there are no provisions with DC's building regulatory process to step in and suggest better design principles with the aim of generating a better outcome that will stand the test of time.

Triangular building, Culver Hotel, Culver City, Los Angeles

Conclusion. High quality, often historic, architecture and urban design is the foundation of the city's identity and competitive advantage.

The built environment as an ensemble, positively or negatively, has been an issue with corridors--avenues and streets--for centuries. Typically, commercial sections of corridors can be a polyglot while residential sections, such as on Connecticut Avenue or 16th Street in DC (or Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia) have an architectural coherence often missing in the other sections.

Today, it seems as if buildings are thrown up with little consideration for how they contribute to the built environment beyond the lot lines. This was not the case for buildings constructed before 1945.

Construction during the urban renewal era has accentuated the split as new buildings are lot specific and generally haven't been designed to connect to, extend, and strengthen the extant built environment

.

H Street Connection, a strip shopping center, was constructed in the 1980s. Behind it is an urban renewal era senior housing development.

Before, buildings were constructed to last and the developer typically intended to own what they built for a long time, further "incentivizing" them to build well. Architects designed buildings to complement the existing context and building stock present around the site.

Then, it wasn't as important to "regulate" design because it was a given that buildings would be designed to be attractive and new buildings almost categorically were an improvement over what they replaced.

Today's conventions for development and design are much different, and it is much more likely for new construction to be subpar compared to buildings constructed 70 years ago, or earlier.

Because the building regulatory process is focused on individual buildings rather than the ensemble, "extraordinary" steps are required to protect and project the interest of the built environment as a whole.

That's why I argue ("Changing matter of right zoning regulations for houses to conform to heights typical within neighborhoods, not the allowable maximum") that the city's built environment should be managed and regulated as if the entire city is a heritage area.

That doesn't mean that every building has to be designed as if it were a monument, but it would provide for design review where there are no provisions for such review currently.

But to build the consensus for that will take years, and in the meantime, the architectural character and quality of the city's major streets continues to be diminished by insensitively designed infill construction.

Therefore, as recommended in the Comprehensive Plan, a process should be instituted to provide design review for gateway sites and the city's major avenues and streets, because of the extranormal position these elements play in the city's built environment.

Today, it seems as if buildings are thrown up with little consideration for how they contribute to the built environment beyond the lot lines. This was not the case for buildings constructed before 1945.

Construction during the urban renewal era has accentuated the split as new buildings are lot specific and generally haven't been designed to connect to, extend, and strengthen the extant built environment

.

H Street Connection, a strip shopping center, was constructed in the 1980s. Behind it is an urban renewal era senior housing development.

Before, buildings were constructed to last and the developer typically intended to own what they built for a long time, further "incentivizing" them to build well. Architects designed buildings to complement the existing context and building stock present around the site.

Then, it wasn't as important to "regulate" design because it was a given that buildings would be designed to be attractive and new buildings almost categorically were an improvement over what they replaced.

Today's conventions for development and design are much different, and it is much more likely for new construction to be subpar compared to buildings constructed 70 years ago, or earlier.

Because the building regulatory process is focused on individual buildings rather than the ensemble, "extraordinary" steps are required to protect and project the interest of the built environment as a whole.

That's why I argue ("Changing matter of right zoning regulations for houses to conform to heights typical within neighborhoods, not the allowable maximum") that the city's built environment should be managed and regulated as if the entire city is a heritage area.

That doesn't mean that every building has to be designed as if it were a monument, but it would provide for design review where there are no provisions for such review currently.

But to build the consensus for that will take years, and in the meantime, the architectural character and quality of the city's major streets continues to be diminished by insensitively designed infill construction.

Therefore, as recommended in the Comprehensive Plan, a process should be instituted to provide design review for gateway sites and the city's major avenues and streets, because of the extranormal position these elements play in the city's built environment.

Anne Brockett is the developers' best friend. As long as she remains in charge, historic preservation will continue to be the joke that it has recently been.

ReplyDeleteGS

Lots of good stuff here.

ReplyDeleteWhen I think diagonal avenue, I think of of Barcelona.

I've wasted a lot of time yesterday for an article in a the british press on the problem of "long roads" and commercial strips.

I live in a glass wall building. The amount of light -- fantastic. Views -- great. Privacy and the need to have a set piece facing outside -- not good. Heat terrible!

The precedent for this is the PA development corp, which worked out pretty well -- the FBI building aside.

Where we really need that effort in DC is along RI and NY avenues.

thanks for looking, albeit unsuccessfully, for the article you remembered.

ReplyDeleteSadly, I haven't been to Barcelona, but I saw a great presentation at the 2004 APA meeting on Cerda. I didn't mention Haussmann, but of course, his work is pioneering (and a similar kind of urban renewal comparable to various 20th century programs in the US).

Many examples of course.

And while it's true that NY and RI Avenues are important, absolutely, so is Georgia Avenue, Connecticut in the area of the Vann Ness station and the odd new development, H Street, etc.

It's a shame that there has been no move to actualize the recommendation in the Comp. Plan. So it's all talk and b.s., because day to day, the value of the ensemble diminishes.

Although on Georgia Ave. at least, there are some odd examples of decent buildings. There's one at Lamont St. or something like that, on the east side. I think the Park Place buildings are decent enough. Same with the building that replaced the Safeway. There are some more "modern" examples, including one going up now, maybe at Shepherd St.?

I don't really have the time, but I thought it would be interesting to go up Georgia Ave. and do a "survey" of all the apartment buildings.

if you google "el diagonal" in Barcelona, lots of good pictures, better than the metropolitan building shot you have on madrid.

ReplyDeleteMy internal summary of the british piece was "streetcar era good for building residential, not so great for commercial as it lead to long streets that are hard revitalize"

(side note --the retail on 14th street here is very surprising to me. seems to be doing well)

in the early part of the last decade, the Nat. Main Street Center was working with LISC, which created an initiative called the "Center for Commercial Corridor Revitalization" or some such.

ReplyDeleteThe second entry in the blog is an article I wrote published in the Philly Daily News about lessons from DC relevant to that city. It was sparked by the 2003 "Urban Forum" which was the LISC version of the Main St. conference.

They were focused on demonstrating that the Main St. model isn't appropriate for corridors.

They were right and they were wrong. For "what you said" corridors are difficult to improve.

EXCEPT at nodes, and you build/extend outward from nodes. That was the failure with the LISC initiative. You have to make choices and focus on where your opportunities are strongest and build outward from there.

(That's what I recommended in Lawrenceville, PGH, when they were/are dealing with a 5 mile long corridor that includes dead steel plants and amazing commercial nodes both.)

AND LISC WAS FOCUSED on demonstrating the value of "the professional and top down approach" of community development corporations. BUT THE REALITY is that a nonprofit needs the "personnel" heft of the volunteer Main St. model to get more people, especially with a broader range of experiences, involved compared to the number of professional staff that can be funded to do it.

But at the same time, volunteers are good for some things and not others (e.g., business recruitment).

LISC's initiative "failed." Which didn't surprise me. They didn't really know what they were doing I don't think, but they developed some good materials, funded some other stuff, e.g.

http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/urban-studies-and-planning/11-439-revitalizing-urban-main-streets-mission-hill-egleston-square-boston-spring-2003/

but I can't seem to find a link to the very old, out of print "study" that was produced initially.

14th St... you have to think of it over a 15-20 year span. In the "initial" period of the modern post 2000 revitalization, it wasn't able to support "retail" until recently, where the addition of population in multiunit buildings hit critical mass and can support retail as opposed to restaurants.

ReplyDeleteIt takes a few phases. Whole Foods repositioned the area. But outside of convenience retail, a lot of the earlier entrants (Hecho Mexico, Muleh, Garden District, etc.) ended up failing.

Now with a bigger population and more turnover within the preexisting housing stock you can begin to support retail more.

2. There was a funded "arts promotion" marketing initiative a few years ago that I wrote about, said was misguided (long story, I won't go into), I said that "design" is the retail opportunity. And when West Elm failed downtown, I wrote that they picked the wrong location, that they needed to be on 14th St.

And when Shallal et al fought Room & Board I wrote they were wrong, that (1) thriving corridors need some chains, especially exemplary companies, to help position and brand the district and to set high standards (2) and because their promotion and advertising brings new audiences to the street which are then shared with adjoining businesses.

I don't think people really understand that this is a process with phases and that it takes a long time and it is continous.

3. e.g., in my neighborhood there is "an effort" using online to "recruit" TJ's to the neighborhood.

I said that the sentiment is great but that the neighborhood's RTA population is 1/6 of either FB or 14th St. and 1/3 of Capitol Hill, so instead of focusing on something that isn't achievable, why not focus on something that is (I suggested approaching Streets--besides their stores in DC and Arlington they opened one in Downtown Baltimore--and putting it in the forthcoming EYA apartment building at the Metro).

The waste and lack of "better" focus is why these processes take so long, because so much time is wasted on working on things that won't come about.

a few years ago, working with a consultant who turned out to be wacked, we submitted a bid to do a market study for Columbia Heights, after DCUSA opened. But in the 2008 downturn then Mayor Gray cancelled all grants to nonprofits, so the effort was scotched.

ReplyDeleteOne of the main points I made is that the "plan" for Columbia Heights' retail was only for the initial phase, that they never planned beyond the original recruitment and focus on convenience retail and that to build and strengthen and extend the district they needed to be focused on "what's next."

This is pretty typical of our commercial district planning in DC.

14th St. is a great lesson in what's possible as population grows.

BUT at the same time, the limited amount of potential retail inventory and the shift in consumption to prepared food and the prominence of restaurants makes it difficult for straight up retail to compete with restaurants for space.

Fortunately the new buildings on 14th St. have added new inventory which retailers have been able to compete for.

the other thing that is incredible, would be interesting to do a cross-city study on, is the addition of grocers to the city.

ReplyDeleteThis has come up with Eastern Market, where we are finally doing some internally directed market research -- still simple -- that I have helped shape. I have been saying the same things since I've been on the board since 2007, but only now people are listening, I argue, only because business is down.

In the retail trade area for Eastern Market, in the last ten years we have either built or planned, 3 new Harris teeters, 2 new Whole Foods, 1 new Walmart, 1 new Giant, 1 new Aldi, 1 new Safeway, 1 completely rebuilt Safeway, and a revitalizing Union Market. That's in addition to a couple of hyper small markets (Yes and one on Mass Ave. NE) and two other Safeways.

I don't think there is one city neighborhood in the country with as many grocery stores.

2. To some extent, the same is the case with your area. 2 rebuilt Giants, 2 new Whole Foods, 1 new Harris Teeter, 1 new Trader Joes, 1 new independent , and 2 existing Safeways plus 2 independent Hispanic markets in Mt. Pleasant.

There's still more in Capitol Hill/H Street.

That has made the Eastern Market vendors marginally more conscious of the need for change.

Well interesting questions.

ReplyDeleteAlso see article on Glen's:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/going-out-guide/wp/2015/11/10/glens-garden-market-to-open-second-location-in-shaw/

(has the post local coverage improved over the past year?)

Walked though the entire north shaw area and it is impressive.

Raises the old question is whether on a city "decay" whether a natural phenomenon or more deliberate and the corresponding lack of investment.

Saw another good british article on "Filtering" on the failure of that theory.

I'll try to track it down. There is good discussion of filtering in Goetze's work.

ReplyDeleteThe thing is that I would argue is that the theory (basically the U Chicago theories of Park et al dating to the 1920s) is they were based on a specific phase of national economic development marked by constant growth, industrialization, and expansion.

So people moved outward as their economic circumstances improved and there were new immigrants either from rural to urban or from nonUS to US to replace them.

We are not in the same economic circumstances now.

As a broader range of amenities and the ability to not be car dependent is of increased interest, cities can compete, based on their urban design characteristics hailing from the walking and transit city eras.

I actually had a similar realization yesterday about JJ's point about the necessity of a large stock of old buildings.

ReplyDeleteas you know, it wasn't because she was a preservationist, but because paid off buildings had lower running costs and space was cheaper.

But again, a lot of her precepts were based on the stage of the US economy at that time. Still growing, still a lot of small businesses, especially in NYC.

Now the economic sector is organized differently, cities like NY and SF and Boston are "global" and the capital flows are different and especially, retail is organized differently.

Now I argue that you need to be more purposive in creating and maintaining those kinds of spaces necessary to seed innovation (like the discussion in my piece "arts, culture districts and revitalization").

The velocity of change is so strong and pronounced that functions less able to compete on a market basis need to be supported in extra normal ways.

another thing that needs to change is place management, what the authors of a book on an EU study initiative call "place keeping."

ReplyDeleteI am applying for a job at an organization "not around here" that manages a downtown business district and while preparing for my first interview, I looked at a bunch of their annual reports, etc.

Like what I said about planning for Columbia Heights or even 14th St. (which unlike Columbia Heights has developed organically, without a plan), they have gone through many stages. Their effort is now 25 years old, and has gone through phases.

Anyway, I was so blown away by the basic standards they have for maintenance of specific places, how often they are powerwashed, trash can liners aren't just emptied and replaced, they are also deodorized, places are gumbusted, etc.

While Downtown DC BID has done some gumbusting, there is no question we need a regular schedule for it in highly trafficked places (e.g., DC/USA, most in-city Metro stations, highly used bus stops, etc.).

DC really needs to up its game.

I go through this Article very nice .Thank you for sharing this article

ReplyDeleteWebsite Designing Company Bangalore | Website Designing Companies in Bangalore

This is a great post about special design guidelines are required for DC's avenues.

ReplyDeleteBest mobile application development company

ReplyDeletemobile app development company

mobile app development company gurgaon

mobile app development company India

rpa companies

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete