In the previous entry, charlie commented that an item I left off the list was DC's launch of dynamic pricing of street parking in the Gallery Place district of the city ("Pay-by-space parking rolls out in Chinatown/Penn Quarter," WTOP).

My response was that it's too soon to tell how "transformational" something like this really is. An announcement on its own isn't enough.

Past writings on parking include:

-- Parking districts vs. transportation/urban management districts: Part one, Bethesda (2015)

-- Parking districts vs. transportation/urban management districts: Part two, Takoma DC/Takoma Park Maryland (2015)

-- Testimony on parking policy in DC (2012)

-- Municipal taxes and fees #2: parking (2010)

-- The High Cost of Free Parking (2005)

The comment led to a spirited discussion about how I would approach parking in the core, in a systematic way, which the city doesn't do, and that I have come around to the position that regardless of the prioritization of walking, biking, and transit in Washington, DC especially, parking still needs to be accommodated and if managed and planned for, deleterious effects are minimized.

Parking sign, Shreveport, Louisiana. Flickr photo by Robby Virus.

Planning for parking and curbspace management. One of the problems with city planning generally is that it usually isn't so much fully thematically comprehensive as it is focused on whatever the city is directly responsible for, such as the management of city-owned assets or zoning.

As a result, local government parking and curbside management plans usually ignore privately held parking assets, so a comprehensive plan that addresses "parking" holistically and includes all assets, public and private is not produced.

In many places that doesn't matter so much, because usually a city or county agency is also tasked with building and operating parking structures. Therefore the city's "parking plan" includes off-street and on-street parking assets.

-- "State of Parking in Lancaster (Pennsylvania)" white paper, Lancaster Parking Authority, 2015

-- Hoboken, NJ parking master planning process

-- Norwalk (Connecticut) Downtown Parking Master Plan

From the Norwalk plan: The research is clear that if parking maximums are used and parking minimums are eliminated, or even reduced, then supportive programs or policies must be put in-place to manage spillover onto local streets and private lots. Cities must remain nimble and flexible to respond to unique situations, and work collaboratively with property owners to find ways to reduce parking demand over time.A parking lot off Pennsylvania Avenue NW at 3rd or 4th Street NW. c. 1924

Current conditions. But in DC, lobbying by private interests ("L.B. Doggett, Jr.; Parking Tycoon, Civic Leader," Washington Post) decades ago prevented the city government from developing municipal parking options beyond the provision of street parking.

More recently, with the increased utilization of the subway as a way to get to and from work in Downtown--the subway opened in 1976--and densification and the height limit, provision of parking became less viable, when before there had been surface parking lots and dedicated parking garages.

Theoretically, the business improvement districts function by default as "transportation management associations" for their areas, and in many places provide that kind of coordination function. In DC, again, that is not so much the case. The BIDs appear to rely on third-party information systems to provide this information. While there are advantages to this in terms of currency, there is something to be said for published maps and other methods.

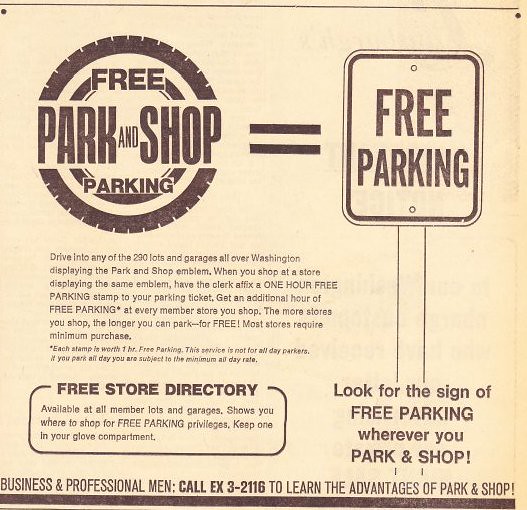

Historical efforts at parking coordination by the private sector: what happened to park and shop/validation programs? The funny thing is that in the 1950s ("Exhibit tells how Milton Bradley's Park & Shop game was invented," Allentown Morning Call), most major cities developed "park and shop" parking and validation programs to compete with the new suburban shopping mall paradigm, which was accompanied by acres of free parking.

DC was no exception. Over the years, I have acquired a few items from the program (a map, booklet, and an ad from the Washington Star).

Downtown Park and Shop ad, Washington Star, 4/10/1968.

Downtown Park and Shop ad, Washington Star, 4/10/1968.In the early 1950s, the "Washington Parking Association" published a map of the parking lots and structures serving downtown.

Later, working with merchants, the parking interests developed a parking validation program, where people could get a certain amount of free parking paid for by merchants, in return for purchases.

That system eventually ceased to exist, probably because Downtown DC was firmly supplanted by suburban shopping malls as a primary regional shopping destination, and most of the previously participating retailers went out of business.

Still, DC still has a major downtown-based department store--a Macy's--which helps to attract some additional major retail such as H&M and Forever 21. But most people aren't likely to drive to Downtown to shop, especially not from the suburbs, which are burgeoning with retail options closer to home.

At the end of the entry, images are posted from the 1953 Washington Parking Association brochure.

Managing street parking better, to push people into off-street parking. The idea behind raising the price of parking on the street is that it generates congestion because of people searching for a space. (Fortunately for the most part DC isn't scarred by surface parking lots, which typically mar central business districts in all cities excepting New York.)

Underpriced street parking also discourages private companies from making parking available, which is a poor use of an existing resource. Instead, in most DC office buildings parking is managed more as a tenant amenity. Profit maximization by marketing to non-tenants or itinerant users is not a priority.

Cities at cross-purposes when managing as a public asset space dedicated to parking: parking meters and tickets as a major revenue source. On the other hand, as charlie points out, because cities like DC rely on parking meter revenue and fines from parking tickets as a significant source of revenue--for DC more than $100 million annually--cities may be disincentivized to manage curbspace in a more transformational fashion ("End of an era: Technology is changing the way we park as tickets decline," Washington Post. But it's a fine line between collecting money for parking and discouraging patronage, especially of people who get ticketed.

This is also an issue with "speed cameras," which issue tickets for speeding. In either case, when residents are recipients of a majority of tickets, automobilists come out in force against such programs ("Handful of Traffic Cameras Issue Most D.C. Tickets," NBC4; "Report: $55 million DC tickets went unpaid last year," Washington Post).

Using "parking" space for other purposes. Outside of the revenue implications, from the standpoint of sustainable mobility, placemaking, and asset management, there can be better ways to use space currently dedicated to street parking.

Examples include dedicated transitways for bus or streetcar/lightrail, parklets, sidewalk widening, cycletracks and bike lanes, bike parking and bike sharing stations, trees and plantings, etc.

The "Parking Day" movement highlights that there are better uses for srce street space than cars.

But all that too conflicts with people's perceptions that parking should be easy and "right there," along with the reality that in the suburbs parking is often free, especially at shopping centers, and business interests, which see street parking as an important element of attracting customers.

A more comprehensive approach to parking is required: dynamic pricing of street parking is but a single element. The dynamic parking pricing initiative in DC's Gallery Place district doesn't rise to the level of a transportation game changer because it is a one-off response to a problem/issue that requires a number of responses, integrated into a comprehensive "program."

The Comprehensive Downtown Parking Management Plan for Auburn, Washington--admittedly a small place compared to Downtown Washington DC, which is one of the nation's largest center city business districts--is a model for what other cities, especially in places of high mobility activity, should be doing. The model has a nice section of best practices and emerging and innovative approaches.

TCS International is a firm specializing in the creation of dynamic district parking wayfinding systems. This photo is from San Jose, California.

First, I don't even know what the inventory is of street parking spaces versus private spaces, and how many spaces are part of the program. From the map in the article, it doesn't seem particularly large.

Second, there isn't a comprehensive provision (map/tables) of all the parking options (well, there is through the Best Parking website's DC page) in the central business district now.

Seattle's e-Park program is another example of providing a real time information system for parking availability at off-street parking garages, using signage and mobile apps. Participation is voluntary but includes public and private locations. Park Assist is the vendor for the program (case study; presentation).

Third, there isn't an integrated parking information system, using signage of various forms and integrated online apps, to direct people to available parking in an efficient manner. Yet more and more, we are seeing these kinds of systems being installed in parking garages in the suburbs, at shopping centers, and at airports.

Fourth is the option of providing coordinated valet parking within a commercial district, something I've seen in other cities, but never in DC. Although here and elsewhere, various apps and services are stepping into the breach ("Luxe Valet wants you to never park yourself again," USA Today), but the "need" is fostered by these planning failures.

Fifth, cities, BIDs, and transportation management associations need to ensure that the attractions in their districts, such as theaters or sports facilities, encourage people to use modes other than the car, but provide information and support for all modes regardless. For example, providing group fares for riding transit, bundling transit into ticket prices (Sacramento's transit agency has proposed this for the new Sacramento Kings basketball arena), and making arrangements for parking options, are some of the tactics that should be employed.

Requiring transportation demand management planning for sports facilities should be a basic requirement for all cities. DC doesn't do so for the Verizon Center, but it is likely a majority of attendees don't drive. Unlike the Washington Nationals, the Arena has a standing contract with the local transit agency to extend hours for subway service if necessary, but they don't have an overall plan. A couple TDM plans for a sports facility that I've come across include Wrigley Field in Chicago and for Barclays Arena in Brooklyn.

Since local governments typically provide some financial support to such facilities, they should include TDM requirements in the master contract with the team/facility operator.

A rise in neighborhood activity centers has created new demands for itinerant parking outside of the core. Regardless of needs in the central business district, as charlie points out, it is in the "neighborhoods," in districts that serve residential, retail, and nightlife functions, like U Street, H Street, and Capitol Hill, where there is a need to step in and provide parking beyond what is available on the street, to facilitate commerce and to limit competition for parking between residents and visitors, as most residents in rowhouse neighborhoods don't have off-street parking.

Providing parking in residential areas that abut commercial districts, office buildings, and transit stations can be complicated by under-pricing of residential parking permits, and misuse and/or under-pricing of visitor parking permits.

Because demand is concentrated at certain times of day, from a market perspective, building additional parking to support commercial uses isn't profitable. If it is to be provided, subsidies or municipal provision may be necessary.

Models worth looking at managing parking at the neighborhood/district scale include the North Park district in San Diego ("Parking boom in North Park," San Diego Uptown News) and the Chestnut Hill district in Philadelphia is another example of best practice, where the Chestnut Hill Parking Foundation manages off-street parking in a coordinated fashion, across multiple lots ("Chestnut Hill Parking Changes," Germantown News; "Drivers avoiding Chestnut Hill's pay parking creating problems for residents, NewsWorks).

Not discussed in the article, North Park also provides coordinated valet parking across the district, rather than leaving it up to individual businesses. And College Park, Maryland manages public parking across multiple privately owned lots, and generates 10% of the city's budget from parking-related activities

-------

Brochure

No comments:

Post a Comment