The idea behind the program was to get languishing properties into productive use, by selling the lien, and the lien owner being motivated to get the tax debt paid with interest by the property owner, when if not paid, the lien owner gets the property and most likely then sells it, which eventually leads to it being reoccupied.

But many of the liens involved people who could no longer take care of themselves well, and people lost properties over tax debts as little as $150 ("Left with nothing" and "Jonetta Rose Barras: What lies beneath D.C.'s tax-lien abuses," Washington Post; "Meet the Man Behind D.C.'s Predatory Tax Lien Practices," Washington City Paper). This problem is slowly being rectified in DC.

Although I will say that activists attempted to raise these issues at the time, but their remonstrations were ignored.

Land banks. In weak real estate markets, acquisition of properties through tax liens and the creation of land banks has been a strategy to deal with disinvestment and abandonment (I don't like to use the word "blight" because blight is a condition that results from disinvestment).

Dan Kildee, at the time county treasurer in Genessee County, Michigan, which is centered around Flint--which has been devastated as a result of the decline of General Motors and the shutdown of multiple automobile manufacturing plants that had been based in and around the city, developed an aggressive tax lien and land banking initiative that became a national model ("Ten years of fighting blight: Genesee County Land Bank," Flint Journal).

Later, Kildee created the Center for Community Progress as an organization to foster the concept and to provide training and technical assistance to communities in similar situations.

My concern at the time when Flint and Dan Kildee got a lot of national media coverage, was that attention failed to make the distinction between "strong" and "weak" real estate markets, and there was an almost blanket support for demolition as the primary strategy ("Genesee County Land Bank says it has demolished 1,800 houses since 2013," Flint Journal. In potentially strong markets, it's far better to save and rehabilitate properties.

It's not enough to acquire property, the trick is building demand so properties can be rehabilitated and occupied.

Wayne County Michigan, where Detroit is located, has been similarly aggressive in land banking. But the problem in weak markets is not necessarily acquiring or assembling properties, it's lack of demand to either buy, renovate, and reoccupy properties, or to build new buildings on now vacant land.

This is why I say "demolition" of properties isn't a solution. A nuisance property may be demolished, but the problem isn't eliminated. Instead, a new problem, a vacant lot, has been created. And often it is harder to develop a vacant property than it is to fix a disinvested property.

The book Bringing Buildings Back is a good resource for addressing the problem, as are focused neighborhood improvement programs like Baltimore's Healthy Neighborhoods Initiative, and Baltimore's resident recruitment initiative, Live Baltimore.

Historic Macon Foundation has been particularly adept at focusing historic preservation housing rehabilitation in neighborhoods in the city's core. One of their initiatives worked with Mercer University, which wanted to help improve the neighborhoods abutting their campus.

HMF argues that their approach has moved from focusing on individual exemplary houses to preserving and improving entire neighborhoods. It's a shift in perspective that still (sadly) is noteworthy and exceptional.

-- Neighborhood Revitalization presentation, Historic Macon Foundation

Over time, some states have developed similar initiatives based on the Main Street commercial district revitalization approach, but applied to neighborhoods. In Pennsylvania, they called it the Elm Street program.

But these programs tend to wane over time, partly because it takes many many years to develop demand and "fix" languishing communities, and because as political administrations change, so do their priorities, and programs such as these are often seen as being Administration-specific rather than "good programs" that need need to be supported over long periods of time.

This residence, at 1517 N Kealing Ave., is owned by Mt. Helix, the worst code violator in the city of Indianapolis. (Photo: Robert Scheer / The Star)

This residence, at 1517 N Kealing Ave., is owned by Mt. Helix, the worst code violator in the city of Indianapolis. (Photo: Robert Scheer / The Star)Indianapolis and tax liens. Starting in mid-November, the Indianapolis Star published a number of articles about problems with the tax lien system there.

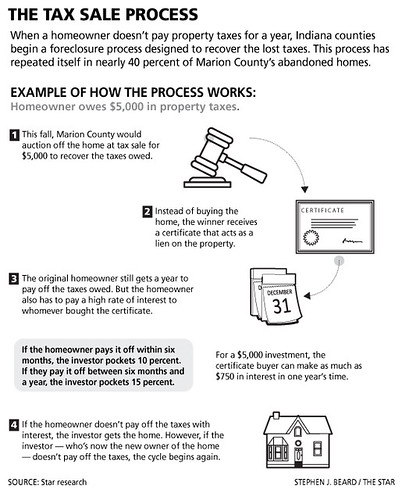

Unlike the system in DC, which from the standpoint of getting properties reoccupied, has worked, because DC is a strong real estate market with greater demand for housing than there is supply, in weak markets, the tax lien process can make the situation worse, not better.

The series kicked off with "Blight Inc.: How Our Government Helps Investors Profit From Neighborhood Decay." From the article:

Indianapolis is pockmarked with 6,800 abandoned homes that stunt property values, attract crime and destabilize neighborhoods. But one of the primary causes is mostly hidden. And it is, in large part, enabled by our own government.Because there is a "national system" for investing in tax liens ("Tax sales support get-rich-quick cottage industry"), which the Indianapolis Star describes as having been created during the Depression, national actors tend to be better equipped to acquire the liens.

An Indianapolis Star investigation has found that, increasingly, the empty house next door is not owned by a bank or an individual, but by one of many investors, often from out of state, who are enticed by the prospects of cheap homes that can be purchased — sight unseen and in bulk — at government tax sales. ...

The Star found that oftentimes these companies don’t make the needed improvements or even maintain their homes. Many of the houses languish neglected and empty for years. Some for as long as a decade. And the system makes it easy for investors to walk away without paying their taxes. In some instances, homes go to tax sale again, and again, and again.

... The Star’s examination of eight years of tax sale data showed investors walked away from more than 6,000 properties and stiffed Marion County for at least $28 million in uncollected taxes. Meanwhile, our government spends millions every year cleaning up trashed properties, issuing code violations, subsidizing redevelopment and responding to emergency calls to unsecured empty homes.

As a result, area residents and organizations who would normally be motivated to take over properties to fix them and to get them reoccupied to help stabilize and improve neighborhoods, rather than profiting from it, are outbid by the national firms ("

This house, at 1909 Cornell Ave., has gone to tax sale four times. It is now owned by San Diego-based Mt. Helix, the company with the most abandoned homes in Indianapolis. (Photo: Robert Scheer / The Star)

This house, at 1909 Cornell Ave., has gone to tax sale four times. It is now owned by San Diego-based Mt. Helix, the company with the most abandoned homes in Indianapolis. (Photo: Robert Scheer / The Star)As the Star points out ("Declining neighborhoods: Indy's auction block) it doesn't make sense that neighborhood decline is furthered by government action because of the way the tax lien system works, rather than being abetted by it.

This particular article is a definitive discussion of the tax lien system, and its problems.

Receivership as an alternative. Not all land banks work out well ("Land bank, hit by scandal, holds back as blight spreads") and frankly, sometimes often alleged nonprofits can be mendacious too, as past history in DC has proven. The Indy Star series also uncovered malfeasance by nonprofits working with the tax lien companies, and failing to improve properties.

But many years ago I learned about receivership statutes in Ohio, which are another model for how to deal with nuisance properties (see "Eminent domain and receivership to "cure" habitual nuisances").

-- Preservation Services - Cleveland Restoration Society

-- Cleveland Restoration Society Saves Historic Van Sweringen Demonstration Home in Shaker Heights – now For Sale to a Preservation Buyer, press release

There, nonprofits can petition to take over a nuisance property, provided the Housing Court approves their plan for "curing" the nuisance. When they fix the property, they can then petition the Court for ownership of the property and waiver of liens. The organization then sells the property to residents committed to maintaining the property. The organization may lose money on the sale, but the neighborhood wins, because instead of a vacant property or lot, they now have a rehabilitated house with residents committed to the house and the neighborhood.

The key element of this process is that the nonprofit can't get ownership of the property until they cure the nuisance. Control is conditional on successful action. Having tight accountability mechanisms is a key difference between successful and unsuccessful programs.

But financing remains a problem. Nonprofits typically don't have a lot of money and staff, so they can do this for only a few properties at a time, and have to wait for the proceeds from the sales of properties before they can take on new projects.

Other innovative programs for neighborhood stabilization. A few years ago I mentioned a Wall Street Journal article about a community-focused bank that had few problem residential mortgages, because they kept the loans they "originated," so they were motivated to be diligent (see "When locally/regionally owned companies make a difference over national firms"). This demonstrates the importance of community-headquartered banks, which focus on portfolio investing, making high quality to residents and businesses within their communities

Cleveland Restoration Society has developed another innovative program with the First Federal Bank in Lakewood (a suburb of Cleveland), where people can get loans from the bank to rehabilitate and occupy otherwise disinvested properties ("Cleveland Restoration Society, First Federal offer incentives to sell vacant, rundown homes," Cleveland Plain Dealer).

This program builds on another CRS loan program, called the Heritage Home Program, which has funded the improvement of over 1,000 historically designated residences. That was funded in part by "Community Reinvestment Act" related financing tied with the City of Cleveland putting its accounts at banks agreeing to fund the program.

>A before (left) and after of a home renovated with the help of the Cleveland Restoration Society's Home Heritage Program. CRS announced an expansion of the program Thursday.

And unlike the firms active in Indianapolis, one company that has purchased a lot of foreclosure properties around the country, REO Homes LLC, has found it is good business to contribute to community improvement efforts in order to build the value of its own properties (see "Interesting wrinkle on neighborhood revitalization: investor fixing nearby properties to raise own property values").

Conclusion. Property tax lien programs can be a negative, not a positive, for community stabilization and improvement, depending on the intent of the companies that are involved. It can make more sense to create different kinds of programs that keep ownership and improvement of properties in local hands, rather than to expect non-local firms to be motivated in the same way to do a great job and focus on long term property and neighborhood stabilization.

(I can't claim to be aware of all the great programs and models that are out there. I do know that many such programs exist and we need to raise the awareness of these programs and what works so that more communities can refocus their programs for better outcomes.)

A side note: too often the web doesn't substitute for high quality investigative reporting by local newspapers. The Star says this is what it did to produce the series of articles:

The Star conducted more than 50 interviews with public officials, developers, residents, experts and corporate executives; and analyzed data from numerous sources, including: Eight years of Marion County property sales data; more than two years of data from Code Enforcement, police, fire and medical services; Marion County property records; and property value data maintained by the Polis Center at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.That's a lot harder than rewriting a press release and not asking any questions concerning whatever remains undisclosed.

The Star also visited Baltimore and San Diego, examined blight reduction programs in five other cities, and reviewed hundreds of pages of academic articles and case studies.

This kind of time, depth and perseverance was once typical of newspapers focused on local reporting and improving communities, backed by the money generated by newspaper sales and advertising. As both sources of revenue have declined precipitously, it is rare for newspapers to take on these kinds of investigations.

Newspaper chains are frequently criticized for dumbing down their papers, but perhaps more than most, the Gannett Newspaper chain has remained committed to funding investigations at many of their newspapers (e.g., earlier this year, the Sioux Falls Argus-Leader produced a nice series on the importance of focused teaching of reading skills).

The Star series definitely rises to the same level as two great Chicago Tribune series, "Squandered Heritage" on demolition of properties eligible for historic designation, and "Neighborhoods for Sale" on real estate development and aldermanic privilege .

- Squandered Heritage Part 1: Search and Destroy (Chicago Tribune)

- Squandered Heritage Part 2: Demolition Machine (Chicago Tribune)

- Squandered Heritage Part 3: Alternatives (Chicago Tribune)

Thank you for providing such a valuable information and thanks for sharing this matter.to get Online pharmacy from Dose Pharmacy medicine.

ReplyDelete