Maintaining Neighborhood Character and the Value of Historic Preservation

Modern rowhouses: an argument in favor of historic preservation.

Modern rowhouses: an argument in favor of historic preservation.This was posted on the Brookland listserv:

Hello Neighbors -- I am a native Washingtonian and Brookland homeowner. I understand the Brookland Historical Development Commission convened a mtg at St. Anthony's to discuss the prospect of zoning Brookland as a bona fide historical district.

As a homeowner, I am vehemently against formally zoning Brookland as historical district & resent such process being proposed without input/discussion by Brookland homeowners.

I am interested in attending the next mtg, of this Development Association. I am also interested in knowing who are the members and how to contact them.

Many of my neighbors knew nothing about the St. Anthony mtg nor about current discussion to attempt historical zoning. It is my experience (and the experience of some of my neighbors) that this issue seems to surface every 5 years or so when a new influx residents arrives. Any information you have or willing to share would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.

Carolyn C. Steptoe

Here is my response:

Typical over-sized house inserted onto smaller lots in historic neighborhoods. This phenomenon is called "teardowns".

Typical over-sized house inserted onto smaller lots in historic neighborhoods. This phenomenon is called "teardowns". Historic districts have existed in the city since 1950, when the Georgetown Historic District was created by an act of Congress. Ascribing an interest in designation to new influxes of residents misses the point (imo).

I think increased interest in designation generally is in response to increased forces of change (which can include new residents), be they economic or other, and the resultant threats of significant change to the built environment.

In the case of Brookland, that would be teardowns generally and the "intensification of land use" meaning in particular the likelihood of the conversion from residential to commercial in the area between the railroad tracks and 12th Street--again, imo.

If I am reading your post correctly, you ascribe the interest in designation to the new residents, when the interest seems more to be a response to this and other changes (people who move in possessing a suburban sensibility about planning and zoning issues, and a lack of awareness about buildings that are historic or at least eligible for designation are happy to replace stone walls with concrete blocks, ask for curb cuts, tear off porches etc.) which is not driven by new residents but by the "old" residents.

One of the things that always surprises me about posts like yours (and similar comments by Linda Cropp in last week's Northwest Current newspaper), is the failure to recognize that the existence and livability of the center city, in this case Washington, is fully a result of the preservation of historic residential building stock and the urban design of the city (cf. Jane Jacobs Death and Life of Great American Cities) small blocks, buildings fronting the street, etc. (L'Enfant Plan). Compare DC to Newark, Cleveland, or Detroit and you'll understand better what I mean.

It is the historic building stock and urban design (as well as the strong continued employment engine related to the federal government and a great public transportation system) that has allowed DC to be viable and competitive as a place to live vis-a-vis the suburbs. I say this despite the city's still somewhat dysfunctional municipal institutions. (I have written about this in the Philadelphia Daily News, as well as in my blog, see: "Updating my list of the "building blocks" of successful urban revitalization" in the March archive.

As an aside, of course, the entire city owes Brooklanders a great debt, because activists in Brookland (along with people from other neighborhoods) managed to fight off the decimation of the city through freeways (if all the proposed routes had been constructed, as many as 200,000 residential buildings would have been destroyed. They weren't and neither was the city. Think Detroit as an alternative that was avoided (that's where I am from and it's on my mind a lot).

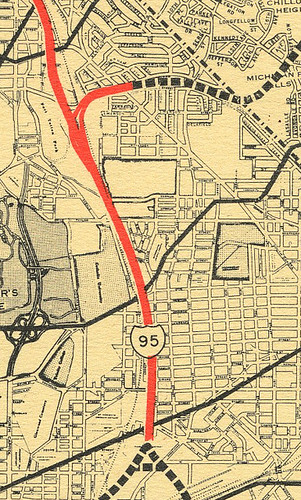

Proposed freeway routing in Brookland, circa mid-1960s.

Proposed freeway routing in Brookland, circa mid-1960s.Now the issue before us is no less significant, to fight off the suburban paradigm of land use and planning (car centricity, single use, low scale and density) that new residents are bringing to bear on the urban built environment that isWashington, DC.

It is not to say that there are no costs to historic designation. It does mean some limits on changes on facades, and yes, no more vinyl windows (and there are ways to address this for those for whom this would be an economic hardship).

But at the same time, it provides for a systematic engagement of citizens in how the built environment is developed in the future, and a base line that protects and extends design quality. In the laws of the city, it is only in historic districts where citizens have this "power". Otherwise, land use is all about "matter of right," and design and quality have no place in the zoning regulations.

Maybe you would make sound decisions about your property. But your house and lot don't exist in a vacuum, they are on a block and in a neighborhood with others. If you make bad decisions, that negatively impacts the value of your property (so what, that's your choice) but it also negatively impacts the value of the properties of your neighbors. Historic designation helps to limit this possibililty (and there are thousands of examples throughout the city where this protection doesn't exist, to see the impact). Since for most people their home comprises by far the largest piece of their household-financial wealth, how other neighbors can negatively impact them through "unsound" actions on their properties really does matter.

For more about the value of preservation in a multiplicity of aspects, I highly recommend the paper "Economic Power of Preservation" by DC resident Donovan Rypkema, as well as his paper about historic preservation and its role in the past and future of the city.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home