Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Nine | Second stage planning for parks using the cultural landscape framework

Gaps in park master planning frameworks

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part One | Levels of Service"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Two | Utilizing Academic Research as Guidance"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Three | Planning for Climate Change/Environment"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Four | Planning for Seasonality and Activation"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Five | Planning for Public Art as an element of park facilities"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning, Part Six | Art(s) in the Park(s) as a comprehensive program "

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Seven | Park Architectural (and Landscape Design) History"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Eight | Civic Engagement"

-- "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Nine | Second stage planning for parks using the cultural landscape framework"

Planning a park at the outset is about creating the landscape design and program. Planning parks at the outset is "simple" in that land features are identified and either preserved or enhanced, and a program--who the park will serve and how it will be done through the provision of a set of facilities including landscape elements--will be created.

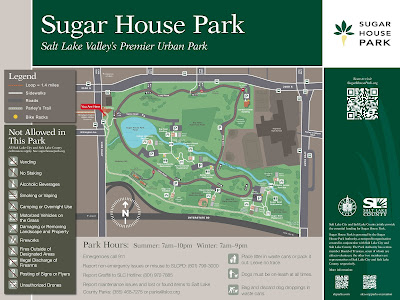

Plans cover land and water features, facilities, intended uses, and programming. At the end of the process one of the ways the plan for the park gets expressed is through a map schematic. While detailed, they are examples of more simplified planning documents.

Updating the park master plan. The planning issue comes up when you update a plan for a park. How large is the park, what features does it have, is it cultural and historically significant or are there elements that deserve more detailed analysis, etc.

Sugar House Park is almost 70 years old, and has different planning needs compared to when the park was created. Items like vegetation and Parley's Creek were not covered thoroughly in the most recent (2008) master plan update process. And there are more issues today like climate change and its effect on the park and patrons, and how to respond.

Many of the "natural features" in Sugar House Park are specified in the post on climate change, "Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Three | Planning for Climate Change." including Parley's Creek, its watershed, and flood control, water conservation, turf and plants, trees/arboretum, and fauna. Topography and viewsheds are key elements also.

Mobility, heat effects and mitigation measures, park and park architectural history, buildings and structures and other facilities, programming, strategy and management of the park are the other necessary elements to have a plan that is truly comprehensive.

So a park or park system plan, to be comprehensive should be a combination of a cultural landscape plan, a regular park design and program plan, a capital improvements plan, an organization and management plan, a branding and marketing plan if the park is signature, a programming plan, and a fundraising plan.

Or would you call those "natural elements" environmental, and call that section of a plan an environmental master plan? Environmental plans have five elements: land, air, water, waste, and energy, some of which you would address only parenthetically in a park plan.

Definitely complicated depending on the nature of the particular park or park system being studied. Because there are so many items, you can call it a cultural landscape plan because that approach is so macro focused and comprehensive.

But maybe the issue is to just make the comprehensive park or park system plan more comprehensive, by including as many of these other items as possible for study, but not calling it a cultural landscape plan per se.

Cultural landscape planning approach. A way to tie together the various planning threads for a park and/or a park system is to use the cultural landscape planning approach, which looks at sites more comprehensively than a typical parks plan.

I think that it is in next stage planning where the cultural landscape approach becomes more relevant to parks planning. For Sugar House Park, the elements to address in more depth would be related to the land, water, vegetation, buildings and history.

A cultural landscape is a place with many layers of history that evolves through design and use over time. A cultural landscape embodies the associations and uses that evoke a sense of history for a specific place.

Physical features of cultural landscapes can include trees, buildings, pathways, site furnishings, water bodies – basically any element that expresses cultural values and the history of a site.

Cultural landscapes also include intangible elements such as land uses and associations of people that influenced the development of a landscape. Cultural landscapes include neighborhoods, parks and open spaces, farms and ranches, sacred places, etc.

However, the cultural landscape approach is usually applied at a large scale. In the US, it's used most often for creating management plans for National and State Heritage Areas, which can cover hundreds of square miles and hundreds of separately owned cultural resources.

ATHA visitor center in Hyattsville, Maryland.Maryland has a National Heritage Area in Baltimore and a program that designates state heritage areas.

Planning occurs at two scales, for the heritage area as a whole (ATHA management plan), focused on the big picture and identifying historic themes, and plans for individual sites like house museums, parks, etc.

The plans for individual units range from park or museum master plans, to house museum plans (building preservation, marketing, etc.).

-- Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes, The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties

-- Protecting Cultural Landscapes: Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes: Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes, Preservation Brief 36

-- How to Evaluate and Nominate Designed Historic Landscapes, National Register Bulletin 18

-- Guide to Cultural Landscape Reports: Contents, Process and Techniques

-- The Alliance for Historic Landscape Preservation

-- The Cultural Landscape Foundation

The most distinctive element about large scale cultural landscape planning is that interpretation is organized around the major historic themes of the area (comparable to identifying the period of cultural significance for a historic district, "What is the Period of Significance and what does it mean for Cleveland Park?," Cleveland Park Historical Society). So the Rivers of Steel Heritage Area in Pittsburgh didn't include one particular mining area as a resource, because it was associated with the steel industry of Cleveland.

One Maryland State Heritage area is the Anacostia Trails Heritage Area in Prince George's County, abutting DC. The state areas focus on highlighting local historic assets and marketing them as a tourism product.

The marketing program may include visitor centers, the organization of cultural resources into "trails," events, wayfinding and interpretive signage, brochures and other elements.Parks and park systems are simpler units than heritage areas and a modified approach to planning at the scale of the cultural landscape makes more sense. Obviously not all parks and local parks system are the same. And only some parks probably rise to the level of high historic/cultural significance.

The challenge is to do more comprehensive planning for the parks that should be planned at that level of detail. I argue a more simplified approach to cultural landscape planning can be adopted for master planning for local parks systems and individual parks. Using the principles, not the level of detail.

Broad Branch Park in New Jersey is a rare example of a local park with a cultural landscape plan, which took several years to create. The report has six volumes and totals over 1,000 pages.

- Existing conditions

- History of the park and critical periods of development

- Hydrology, infrastructure, and historic fabric

- Structures in the park

- Vegetation in the park

- Treatment and management

Such detailed planning for an individual park is beyond the capacity of most parks systems. Note that many parks conduct Cultural Landscape studies using the methods of the National Register of Historic Places.

For example, the Cultural Landscape report (vol. 1, vol. 2) for the Eleanor Roosevelt Historic Site in Hyde Park, New York makes a number of treatment recommendations:

- Improve Landscape Condition

- Protect and Enhance Historic Setting

- Reestablish Historic Field and Forest Patterns

- Perpetuate Historic Managed Vegetation

- Enhance Historic Character of Roads and Walks

- Provide Effective Deer Control

- Maintain Compatible Park Furnishings

- Expand Landscape Interpretation

-- Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan

Again, such reports are focused on identification and maintenance of historic resources, while for a contemporary park or park system, only some elements may be historic, but application of the analytical framework of cultural landscape planning is relevant.

The challenge is identifying certain resources as historic and recognizing this and treating them appropriately, while mixing in other planning approaches to other elements of park resources.

A good way to contrast first stage versus second stage parks planning would be the Rebuilding Central Park plan of 1983, to revive a park constructed starting in the 1850s, or the Bryant Park program, versus the creation of the High Line in Manhattan, Brooklyn Bridge Park in Brooklyn. or Millennium Park (2009 Rudy BRuner Award: Silver Medal winner) in Chicago.

This came up with Sugar House Park and planning for replacement pavilions. I argued the approach was a-historic and failed to acknowledge the relevance of the architectural history of park buildings and structures to the decision making process ("Gaps in Parks Master Planning: Part Seven | Park Architectural History and Design").

For Sugar House Park, the elements relevant to a cultural landscape second stage planning approach would be:

- site history (former prison)

- architectural history of the park (some materials from the prison are used in some structures that exist today) and area

- as well as park architectural history more generally (parkitecture style)

- viewsheds towards the Wasatch Front Mountains

- Parley's Creek (natural) and the pond (man-made)

- topography, in particular the hills (my line is that hills are a competitive advantage for the park compared to other parks in Salt Lake City, which are mostly flat--two areas are especially popular for sledding)

- tree cover and management (treating the trees collectively as an arboretum--we are in the process of getting Level One accreditation from ArbNet, and will continue to develop this concept over the years)

Labels: architectural history, architecture, capital planning and budgeting, cultural landscape, design, historic preservation, provision of public services

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)