When people don't have experiences, site visits are the way to go

In a conversation at the Metro Open House last night, I learned that a contingent of people, including residents not working in transit, went to Portland, Oregon last week to look at their transit options. As I've said before, they have a great system, especially in the center city. But the ridership numbers in DC and across the WMATA system are much much higher. To me, that bodes well for such systems in Washington.

Streetcar model, DC Transit studies.

Streetcar model, DC Transit studies. Seeing can be believing in Portland, Oregon.

Seeing can be believing in Portland, Oregon.I think site visits are a good thing, because change is easy to oppose when you have absolutely no sense that there can be a different way of doing things. This article from the Baltimore Sun, "Ore. transit has mass appeal: A Baltimore delegation travels to Portland to study light rail -- and members enjoy the ride," discusses a similar trip made by Baltimore area residents grappling with proposals for a new light rail line there. Because a number of Baltimore's transit programs were developed in the throes of urban renewal programs, they haven't accomplished all that much-- the Baltimore subway is good for movie sets like "No Way Out," set in Washington, but running away from his pursuers, Kevin Costner ends up on the Baltimore subway--but not for getting you to places you might want to go. So people in the area need to see a working system in order to believe that transit can be great.

One of the tours I went on in Portland was of the new Yellow Line Light-Rail line, which is located in a more "emerging" area of the city, one that has experienced economic distress, closure of manufacturing, and is also more ethnically and racially diverse.

One of the presenters was a citizen, who originally opposed the light rail because of how it was to be funded -- because the original line was to go from Vancouver, Washington to Oregon City, a city east of Portland (you can't really call it a suburb, as its development really came out of the time it took to travel in one day, back when getting around took a lot longer, i.e., in the mid-1800s), it required a bond approval vote of the entire state. Such a referendum failed twice. So the city of Portland through the Portland Development Commission created an "Urban Renewal District" which allowed for the sale of bonds against future tax revenue increases.

To make a long story short, once this person saw the impact of the new line in terms of greater connectivity and the slow but steady improvements in commercial districts along the tracks, he understands much better why expanding transit makes sense, and today he is a strong supporter.

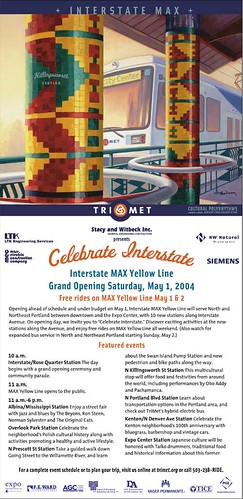

Opening events for last year's debut of the Tri-Met Yellow Line in Portland, Oregon.

Opening events for last year's debut of the Tri-Met Yellow Line in Portland, Oregon.The Portland Yellow Line is interesting for another reason. It provides service in two areas that have terrible stories to tell. The first is that the Expo Center was the site of a major Japanese-American relocation camp during World War II, when Japanese-Americans were interned out of beliefs that there were a threat to national security. The second was an African-American community of industrial workers, Vanport, was wiped out when the dikes-levees broke in 1948, in a fashion similar to what happened in New Orleans.

Tri-Met has guts, so does Portland (it's amazing to compare what Portland did in terms of public art on the Yellow Line vs. what most cities do and certainly the unwillingness to accept challenging art on the World Trade Center site in Manhattan).

They committed to public art for the entire Yellow Line-Interstate Highway project. Each station has different themes, and the Expo Center site has an extensive array of work related to the interning of Japanese, while the station near Vanport has renditions of objects once owned by the people that lived there--these objects come up after rains and floods of this now wetland area. Similarly, other stations reflect Native American traditions, etc.

Valerie Otani addresses the theme of Japanese relocation during World War II at the site of the 1942 Portland Assembly Center. Traditional Japanese timber gates strung with metal "internee ID tags" mark station entrances. Vintage news articles are etched in steel and wrapped around the gate legs. (The artist spoke to us on our tour. And the headlines of the newspapers included in the work were vicious and racist. )

Valerie Otani addresses the theme of Japanese relocation during World War II at the site of the 1942 Portland Assembly Center. Traditional Japanese timber gates strung with metal "internee ID tags" mark station entrances. Vintage news articles are etched in steel and wrapped around the gate legs. (The artist spoke to us on our tour. And the headlines of the newspapers included in the work were vicious and racist. )

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home