If the U.S. is addicted to oil, is President Bush the chief pusher? Musings on transit.

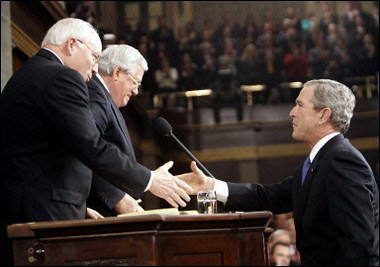

US President George W. Bush shakes hands with Vice President Dick Cheney(L) and Speaker of the House of Representatives Dennis Hastert(2L), R-IL, in the House Chamber during his annual State of the Union speech before a joint session of Congress at the US Capitol in Washington, DC(AFP/Pool/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

US President George W. Bush shakes hands with Vice President Dick Cheney(L) and Speaker of the House of Representatives Dennis Hastert(2L), R-IL, in the House Chamber during his annual State of the Union speech before a joint session of Congress at the US Capitol in Washington, DC(AFP/Pool/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)While I have read Michael Schade's "State of the Circle" address, I haven't quite mustered the energy yet to read the full Presidential "State of the Union" address from last night. I did read the headlines though... and President Bush mouthed some generalities about the "oil crisis." On the other hand, see this somewhat intelligent op-ed (probably because it's from Brookings) from the Washington Times, "Regaining energy leverage."

However, the op-ed focus on technology fixes such as biofuels ignores the fact that the segregated use, automobile-connected sprawl development paradigm is "fueled" by access to relatively cheap energy supplies, and that sprawl living generates much of the U.S. demand for gasoline, of which 65% of the total amount of oil consumed in the U.S. is for gasoline.

Much of the need for gasoline could be eliminated, or at least significantly reduced, through reorienting the development paradigm towards compact development that is mobility rich in options other than the car, and where development is linked to transportation systems, and transportation systems are continually improved and extended.

As long as it is politically impossible to raise gasoline excise taxes--something suggested by Tom Friedman in the New York Times within the last couple weeks, but as a letter writer responded, everyone who voted in favor of such a policy would be booted out in the next election--people will not make sound decisions about transportation, residence, and jobs, or at least, their decisions won't be colored too much, for quite some time, by the real fact that each gallon of gasoline is not replaceable. (Somewhere I saw a figure of $7 per gallon imputed as the cost per gallon of the Iraq War.)

Exxon and Mobil signs are seen in Quincy, Massachusetts in an undated file photo. Exxon Mobil Corp. on Monday fulfilled the corporate fantasy of reporting the most profitable year in U.S. history, only to be met with fierce public outrage at the achievement. (Jim Bourg/Reuters)

Exxon and Mobil signs are seen in Quincy, Massachusetts in an undated file photo. Exxon Mobil Corp. on Monday fulfilled the corporate fantasy of reporting the most profitable year in U.S. history, only to be met with fierce public outrage at the achievement. (Jim Bourg/Reuters)As the papers reported yesterday, it's a good year for the oil industry, and Exxon alone netted $36 billion in profit last year. That's a lot of money. And, I'm sure that their tax lawyers are on the job so that very little of that gets taxed... (See "Exxon Profit Sets Record, Stirs Anger: Its annual and quarterly profit are the highest for any public corporation, but consumers see red" from the LA Times.)

Meanwhile, the fact that 50% of the cost of roads is borne by local, state, and federal government budgets, not by gasoline excise taxes and other fees, further disconnects drivers from the financial impact of their decisions.

Speaking of this, the Washington Times also reports about an anti-tax coalition mounting a campaign against plans in Virginia to increase taxes to build more roads, "Group to run radio ads against tax plans." How the Washington Times terms the group "Americans for Prosperity - Virginia" a "grass-roots government reform group" is beyond me. These people need to read some Adam Smith and his discussion about public investment for the greater good.

Reform? I am not a big roads fan but this is definitely a case of insane thinking. You want to drive. You want roads to be given to you, but you don't want to have to pay for your (bad) choices.

Kimberly Viviano, Viviano + Company, Oak Park, Illinois. "People Powered." The Big Idea: A system of signs posted along Chicago's lakefront would inform drivers and bicyclists of the human, financial, and environmental benefits of riding a bike to work versus driving a car. Courtesy Viviano + Company, from Metropolis Magazine.

Kimberly Viviano, Viviano + Company, Oak Park, Illinois. "People Powered." The Big Idea: A system of signs posted along Chicago's lakefront would inform drivers and bicyclists of the human, financial, and environmental benefits of riding a bike to work versus driving a car. Courtesy Viviano + Company, from Metropolis Magazine.What this kind of thinking does is continue to support a false dichotomy between public financial support of transit, versus public support of the road infrastructure. (And I recognize that roads do have broad public benefits that extend behind the privileges afforded to the drivers of personally-owned automobiles.)

For example, today's "Sprawl and Crawl" column in the Examiner has a letter from "Dawn" asking if dedicated funding for WMATA, the Washington region's public transit system (see "Washington's Metro: Deficits by Design" for the reasons why such a course is suggested) will limit fare increases.

I know I am too pro-transit, but this is not very intelligent thinking. If roughly 50% of the funding of WMATA comes from government and other sources, and 50% comes from fare revenues, and the plan is not necessarily providing more government revenue, but "merely" dedicated government revenue, how will it lead to reduced fares?

As a letter to the editor in the same issue of the Examiner from Alfred Harf, executive director of the Potomac and Rappahannock Transportation Commission, states:

any plan that doesn't earmark funds for transportation funding in a long-term manner "compels transportation to compete for funding with other necessary state government expenditures for general fund resources and prevents...local governments and public transportation providers...from multiyear planning as transportation requires." (This letter is not yet available online.)

Nonetheless, these two letters raise an important point, that people feel like they are paying money towards a public transit system, and either not getting benefits from it, or not enough benefits, while they fail to acknowledge how much of their (and other people's) taxes go to the road system.

All told, the Springfield Mixing Bowl project for Virginia's I-95 will cost $1 billion. Washington Post photo by Kevin Clark.

All told, the Springfield Mixing Bowl project for Virginia's I-95 will cost $1 billion. Washington Post photo by Kevin Clark.Speaking of disconnection, Steve Eldridge, the Examiner columnist incorrectly "informs" the readers of the Examiner that "Taxes drivers pay on gasoline and related services such as license and tag fees feed this pot at the state level so, in large part, those who use the roads pay for them (and for transit whether they use it or not)."

Mr. Eldridge needs to read the paper on highway funding dilemmas by University of California-Berkeley Professor Martin Wachs, entitled "Improving Efficiency and Equity in Transportation Finance," and published by the Brookings Institution. (I was introduced to this paper by Neil Peirce in his column "GAS TAX HIKES: NEEDED BUT POLITICALLY PERILOUS," from May 2003.)

Remember these numbers, one lane of road in one hour can move:

900 cars

6,250 people on local bus service

10,000 people on bus rapid transit

16,250 people on dedicated rail systems (light rail, subway, heavy rail).

Where is the better public return on investment, road building or transit, in terms of enhanced mobility and moving the most people?

Of course, the development paradigm needs to optimize the links between residence, transit, and the places we want to go, in order to make a transit-rich system work.

Index Keywords: energy; transit

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home