Sprawl was driven by more than just cheap land and cheap schools

Subdivision in the Baltimore suburbs. Photo: David Hobby, Baltimore Sun.

Subdivision in the Baltimore suburbs. Photo: David Hobby, Baltimore Sun.David of Rethink College Park wrote a comment on the Shrinking cities entry, and my response is too long for the commenting software to include it in full. Here goes:

Sprawl is more than just cheap land and cheap schools. In many respects it was a deliberate transfer of wealth from the center city to other parts of the metropolis.

It also reflects planning history for the last 100 years--a response to the belief (somewhat true in the first part of the last century with the rise of large scale manufacturing) that cities were gross, noisy, dirty, unsafe, unseemly places.

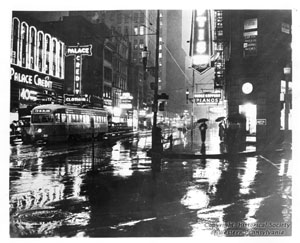

Downtown Pittsburgh at 9:20 AM (1945). Smoke control ordinances were enacted in 1947. Newman-Schnidt Studio.

Downtown Pittsburgh at 9:20 AM (1945). Smoke control ordinances were enacted in 1947. Newman-Schnidt Studio.Federal and other government policies supported sprawl (mortgage underwriting and/or appraisal guidelines wouldn't lead to lending in racially integrated neighborhoods, undervalued city properties, etc.). Interstate highways, which helped make suburban and exurban more valuable at the expense of the city, and so forth.

So did academia. Suburban cities were hypothesized seriously in the latter part of the 1890s. The basic design of suburban neighborhoods--followed to this day--was created in the mid-1920s by community sociologists at the University of Chicago (Clarence Perry) to be perfected in the plans for Radburn, NJ by the Regional Plan Association of America.

Post-war sprawl was driven by many trends, including 15 years of pent up demand held back by the depression and the diversion of U.S. manufacturing and consumer resources to the war effort.

Plus, the ideology of Manifest Destiny and the American Dream, plus production residential construction (ranging from William Levitt in New York and Pennsylvania to Kaufmann and Broad in Michigan), and the automobile and highway construction industries--everything was primed.

And the country was wealthy--the only major "first world" nation in the world that wasn't significantly damaged physically by World War II.

In the 1960s, the rise of the riot ideology (and the corresponding "defining deviance down" (Moynihan) led to a further decline in the quality and outcomes of center city municipal activities. Schools in particular (cf. Marion Orr's Black Social Capital.)

1968 riot photo, Washington, DC. Source unknown though I think it's from the book Ten Blocks from the White House, published by the Washington Post. (I plucked it off youtube.)

1968 riot photo, Washington, DC. Source unknown though I think it's from the book Ten Blocks from the White House, published by the Washington Post. (I plucked it off youtube.)(I'm just starting reading an old book from 1979 called Understanding Neighborhood Change and it has a delicious quote about how politicians are rewarded for effort, not for results.)

What I didn't write about, which I write about from time to time, is the transition of an economy based on an "extensive" use of resources (a lot and more) vs. an "intensive" use of resources (less and more efficient).

[Much to my regret, I never wrote this argument up. I called it Prisoners of Progress, influenced no doubt by Kirkpatrick Sale's Human Scale, and had the basics worked out by 1983.]

One advantage Japanese manufacturers have had over the U.S. is the fact that they've had to import the majority of their raw materials. As a result, a concern about waste and continuous process improvement was drilled into their perspective. This is the heart of the Toyota Production System.

This is but one trend impacting the U.S. Another is the trend to a service economy as you state. More accurately than calling this a move to a service economy, is the recognition and implementation of a truly global economy, and the creation of a global market of goods and labor.

Relatedly, the new global economy no longer values sheer mass quantity. Quality matters too. Mass production was the "secret" to the U.S. economy that led the rust belt to great wealth--mass production with few global competitors-- allowing for extranormal profits, and extranormal wages. (Also see Foster's Innovation: The Attacker's Advantage -- I don't think the book is well-written, but it's an important argument.)

It's not like that anymore. Most every industry faces brutal competition.

The global labor market underprices the U.S., and in manufacturing specifically, the U.S. is not competitive in mass produced goods (but still can be in goods with high knowledge-information value).

(And this is a legitimate criticism of immigration too, although I personally am not against immigration. There was an article in the WSJ a couple weeks ago about a stucco contractor in South Carolina whose business went from $900,000/year to $71,000 as his former employees, legal and illegal immigrants from South America, opened their own businesses and undercut his prices--because their perspective on price and value was different and as a result they could seriously underbid him. Plus the immigrant entrepreneurs had more direct connections to the labor force that their former employer had relied upon, making it difficult for him to find and retain qualified employees.)

In the new global economy, the midwest or upstate New York has tremendous locational disadvantages. Coastal cities are still well-positioned.

Generally, the U.S. is screwed. Our population is high, and our wage rates high compared to places like India and China, and our prevailing wage rates will drop.

Unfortunately, the U.S. standard of living and cost of housing, etc., will not drop commensurately. And therefore a lot of people will be comparatively and in real terms, worse off.

Throw in the greater competition for raw materials on the part of China, and eventually India, as well as the likely continued depletion of oil and an increase in prices, and the future looks somewhat challenging.

Of these two quests to retain knowledge workers--young well-trained college students--Toledo Ohio or Savannah Georgia, which city do you think is more likely to succeed.

See:

-- Mayor lobbies city's 'brightest' to stay in Toledo (Toledo Blade)

-- Money, vision needed to get 'young and restless' to settle here (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, registration required)

-- Savannah, The Creative Coast Initiative

From the AJC article:

... exposing how amazingly competitive it is to attract the educated young to communities.

They are drawn to communities that have an appealing quality of life — a much softer and complex issue than offering cheap land, cheap labor, cheap housing and cheap energy (a mainstay of economic development in Georgia for decades).

What does quality of life include? Parks. Green space. Good schools. Comprehensive transit. Bicycle and pedestrian trails. Sidewalk communities. Quality restaurants. Exciting arts, cultural and entertainment venues. Nice climate. Low pollution. Top-level universities. Great neighborhoods. Minimal traffic. Health care. Ample water resources.

Index Keywords: global-economy

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home