The smallest choices have big consequences

In the letter to the editor, "Hung Out to Dry," Elizabeth Oldaker of Culpeper explains why the United States "is behind the barrel" when it comes to energy use, writing:

I must take issue with Jan. 15 letter writer Stefan Hochhuth's manly assertion that "no household consumer product could be replaced as easily as a clothes dryer." Since many neighborhoods forbid outdoor clotheslines, should we hang all our clothes and undies over the bathtub? Our sheets across the living room? I harrumph in Mr. Hochhuth's general direction.

Many years ago, I remember a book published by a local press, Seven Locks Press, about linking the local to global issue--Bridging the Global Gap : A Handbook to Linking Citizens on the First & Third Worlds.

You wouldn't think challenging your homeowners association about hanging up the wash outside would have global implications, but it does both in terms of (1) U.S. energy policy; (2) U.S. military intervention and force projection overseas; (3) balance of payments and trades and international finance; and (4) climate change, global warming, and the environment.

Baldo comic strip, 12/2/2006.

Ms. Oldaker clearly isn't attuned to the implications of her willingness to accept the status quo. Meanwhile, "Bombers Strike Central Baghdad" appears on the front page of the verysame paper containing Ms. Oldaker's letter. According to the article "Dozens killed, more than 140 wounded after two explosions hit market area of Bab al-Sharji."

Things are tough all over.

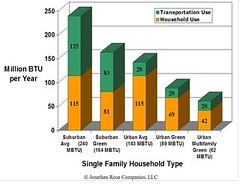

My energy efficiency expert friend disagrees with Amory Lovins, who believes that we can get to energy independence profitably through rethinking how we use energy. But I think the article in last week's issue of the New Yorker (not available online), which discusses some of Lovins' work, is worth reading.

Especially in the light of this very chilling reprint in the Independent of the first chapter of the book, Half Gone: Oil, Gas, Hot Air and the Global Energy Crisis, by Jeremy Leggett. From the piece:

We have allowed oil to become vital to virtually everything we do. Ninety per cent of all our transportation, whether by land, air or sea, is fuelled by oil. Ninety-five per cent of all goods in shops involve the use of oil. Ninety-five per cent of all our food products require oil use. Just to farm a single cow and deliver it to market requires six barrels of oil, enough to drive a car from New York to Los Angeles. The world consumes more than 80 million barrels of oil a day, 29 billion barrels a year, at the time of writing. This figure is rising fast, as it has done for decades.

The almost universal expectation is that it will keep doing so for years to come. The US government assumes that global demand will grow to around 120 million barrels a day, 43 billion barrels a year, by 2025. Few question the feasibility of this requirement, or the oil industry's ability to meet it.

They should, because the oil industry won't come close to producing 120 million barrels a day; nor, for reasons that I will discuss later, is there any prospect of the shortfall being taken up by gas. In other words, the most basic of the foundations of our assumptions of future economic wellbeing is rotten. Our society is in a state of collective denial that has no precedent in history, in terms of its scale and implications.

Of the current global demand for oil, America consumes a quarter. Because domestic oil production has been falling steadily for 35 years, with demand rising equally steadily, America's relative share is set to grow, and with it her imports of oil. Of America's current daily consumption of 20 million barrels, 5 million are imported from the Middle East, where almost two-thirds of the world's oil reserves lie in a region of especially intense and long-lived conflicts.

Every day, 15 million barrels pass in tankers through the narrow Straits of Hormuz, in the troubled waters between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The US government could wipe out the need for all their 5 million barrels, and staunch the flow of much blood in the process, by requiring its domestic automobile industry to increase the fuel efficiency of autos and light trucks by a mere 2.7 miles per gallon. But instead it allows General Motors and the rest to build ever more oil-profligate vehicles. Some sports utility vehicles (SUVs) average just four miles per gallon. The SUV market share in the US was 2 per cent in 1975. By 2003 it was 24 per cent. In consequence, average US vehicle fuel efficiency fell between 1987 and 2001, from 26.2 to 24.4 miles per gallon. This at a time when other countries were producing cars capable of up to 60 miles per gallon.

Most US presidents since the Second World War have ordered military action of some sort in the Middle East. American leaders may prefer to dress their military entanglements east of Suez in the rhetoric of democracy-building, but the long-running strategic theme is obvious. It was stated most clearly, paradoxically, by the most liberal of them. In 1980 Jimmy Carter declared access to the Persian Gulf a national interest to be protected "by any means necessary, including military force".

This the US has been doing ever since, clocking up a bill measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars, and counting. With such a strategy comes a disquieting descent into moral ambiguity, at least in the minds of something approaching half the country. The nation that gave the world such landmarks in the annals of democracy as the Marshall Plan is forced by deepening oil dependency into a foreign-policy maze that involves arming some despotic regimes, bombing others, and scrabbling for reasons to make the whole construct hang together.

America is not alone in her addiction and her dilemmas. The motorways of Europe now extend from Clydeside to Calabria, Lisbon to Lithuania.

Of course, clothes dryers are just a small piece of the puzzle.

Index Keywords: energy

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home