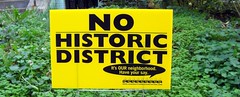

Lanier Sign

For about 4 or 5 years, I have been arguing that to create a historic district, you have to use the processes and structure of a campaign, and can't fall back on sentiment that the buildings are beautiful. (It still hasn't sunk in, or at the least, people are militantly--for the most part--ignoring my suggestions-advice.)

The sign here flips around the argument that I use, it's our neighborhood "and therefore how individuals do things contributes to or diminishes from the neighborhood, and that's a strong justification for preservation protections via regulation.

Instead their argument is "it's our neighborhood" and we should be allowed to f*** it up however we want. Really they should be saying "It's my property, f*** you, I can do whatever I want."

I didn't write a response to Mike Silverman's recent op-ed in the Current because I had already submitted an op-ed to them that they didn't run.

But one of the points he made was so misleading. He said it was tradition to have people opt-in to the creation of historic districts.

This is not true. It is true that in the past decade or so, the National Register of Historic Places has changed their procedures so that property owners can opt out of being listed. (This means that they aren't eligible for historic preservation tax credits if a commercial building, and I suppose untrammeled threat of demolition by the federal government for a public use.)

But whatever the National Register does is irrelevant to how a municipality structures its own regulations about historic preservation.

Something that seems to be forgotten is that preservation regulations usually result from demolitions of important properties by people who don't care. Creating preservation protections that require at a minimum, review procedures before demolition can occur, generally happen as a result of demolition.

We all have stories and experiences of our own about bad landlords and property owners. Why give them a pass and allow them to avoid being concerned about how their decisions impact the whole?

Because I had a project report due that day (which took me all day to finish) I was not able to attend the hearing that was supposed to happen on 11/21 to institute dragonian requirements on historic preservation regulations, initiated by Councilmember Mary Cheh.

The ironic thing, especially because of separate legislation pending to give religious institutions an exemption from local preservation laws, is that these efforts really seem to me to evince little knowledge about why the local law was passed.

Federal laws on preservation only impact how the federal government may impact local preservation resources. It provides for no protections against local efforts, s***** property owners, etc.

In the early 1970s, a number of "National Register" historic districts were created in DC, including Capitol Hill.

Mary's Blue Room, 500 E. Capitol Street NE, demolished by the Capitol Hill Baptist Church in the mid-1970s.

After the creation of the historic district on Capitol Hill, Capitol Hill Baptist Church, which has expanded to take up most of the block between 5th, 6th, A, and East Capitol Streets NE, bought the buildings on the corner of 5th and East Capitol. (HABS photo.)

They said it cost too much to maintain the buildings and they wanted a parking lot for their parishioners. So they tore the buildings down.

Neighborhood preservationists were shocked that they had no tools, no means of input into this decision involving the city's building regulations. That being a federally-designated historic district had no impact when it came to local matters.

From this loss came the development and passage of the local DC historic preservation law in 1978. (It became effective in 1979.)

There is a reason that the law provides for the ability for historic preservation and planning citizen and neighborhood organizations to submit landmark nominations for buildings they don't own. There is a reason that it doesn't provide for opt-out provisions.

Because there was plenty of evidence that many building owners, left to their own devices, will make decisions that diminish the whole, that negatively impact others.

Cleveland has a commercial district zoning overlay called a "business revitalization district" that provides for design and demolition review in areas where the city is investing money and other resources into improvement.

The point of the overlay is that if some building owners make bad decisions, it puts the private and public investments by other actors at risk.

The idea of historic preservation regulations in a center city is to manage the risk presented to property owners by ill-considered decisionmaking by others. In fact, this is the basis of the creation of zoning regulations in the United States.

And eliminating inclusion of churches in terms of the local law takes us back to the 1970s, ignoring a goodly part of the reason the local law was created in the first place.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home