We can Rebuild our roads, but we need to broaden our focus, and (re)build a better transportation system

Today's Parade Magazine has a cover story, "How We Can Save Our Roads: America's highway infrastructure needs money, manpower — and a new vision," on the highway system. My first reaction was, "it's not the roads we need to focus on, but the entire mobility system." However, there is an interesting point in the article that needs to be extended:

Money isn’t all that’s needed, experts say. A solution also will require new ideas about how we design, build, finance, and maintain our transportation backbone.

Build Good—Not Perfect—Roads

Just six years ago, only 44% of Missouri’s highways were rated in good condition. Money was too tight to do much about it. The state’s transportation boss, Pete K. Rahn, decided something had to change.

The problem, he believed, was that highway engineers invariably tried to build the best roads possible. But what if Missourians didn’t always need the best roads possible? What if they were willing to settle for good enough? His answer was a new road-building doctrine he called “Practical Design.”

Today, when Missouri engineers design highways, they aim “not to build perfect projects, but to build good projects that give you a good system,” says Rahn. Practical Design says to “start at the bottom of the standards and go up to meet the need. When you meet the need, you stop.”

On some projects, the new approach achieves identical standards with the old. On others, the differences often are invisible to motorists. A highway through mountains, for example, might have a thinner bed of concrete where it rests on bedrock.

The idea of "practical design" has the ability to be "reverse engineered" and applied more broadly than it is currently being applied in Missouri and other states.

For example, "practical design" of neighborhood roads in a city residential area should mean that the roads don't get built to the level that accommodates speeds of 50 to 75 mph. After all, the posted speed limits are 25 mph, plus these are mixed use areas with plenty of walkers, bicyclists, and non-through road traffic (buses, delivery vehicles, etc.).

People walk in the rain in an area paved with Belgian Block, in central London's financial center. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis) (September 30, 2008)

For example, the over engineered alley between 7th and 8th Streets, next to the Hine Junior High School playground (now occupied by the temporary market building for the Eastern Market public food market) appears to be designed to freeway standards.

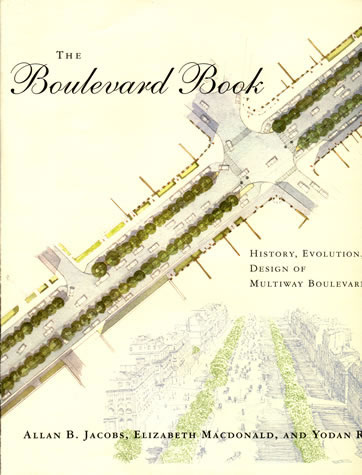

Similarly, highways in cities perhaps should be engineered as parkways and boulevards, rather than the traditional high-speed routes that typify the Interstate Highway system.

This is the flip side of the point I make about using Belgian Block and other similar materials for roads, rather than making all roads capable of enabling the highest possible speeds for cars (and cars are engineered to go very fast too).

Plus, the Post reports today that the Obama Administration is serious about high-speed rail. Sure we're late to the party (Spain, France, China, Japan have showed how it is done or can be done for a long time). But now something is happening. See "High-Speed Rail Signals a Shift."

Labels: car culture and automobility, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home