Vauban, Germany and development at subway stations

I think I have written about Vauban before (at the very least, I know I have images in my Flickr photostream from it). Today's New York Times has a story, "In German Suburb, Life Goes on Without Cars," about what we might call a "subdivision" in the United States, but this particular development, outside of the center city of Freiberg, Germany, was developed specifically to be car free, so cars are banned from the interior of the development. People can own cars, but must park them in parking garages on the perimeter of the development, and they must pay $40,000 for a parking space (that puts people's kvetching on the anc-6a email list about a proposed increase in residential parking permit fees for each additional car beyond one--adding $15 per year for the cost of a second permit, etc.--in perspective). It's mixed use and served by transit, so people get around and accomplish what they need to do just fine.

It relates to the point that I make that joint development projects on Metro station sites should promote transit first, rather than automobile-centric development, such as the proposal for rowhouses, each unit with parking for one to two cars, at the Takoma Metro Station. See the past entry, with written testimony submitted to WMATA about this, in "Comments on Proposed EYA Development at Takoma Metro."

In a blog entry about the Purple line ("Speaking of the Purple Line") I wrote this:

The ability to capture the value of transit adjacency is fully dependent on urban design and intensity of land use. One comment that Councilmember Elrich made is (paraphrased) "if transit is so great for economic development, why do the areas around most subway stations in PG County suck?"

The answer isn't that complicated. It has to do with the structure of land use. You can say the same within DC or Montgomery County, depending on your definition of "suck" (a word that Mr. Elrch did not use).

For example, Dupont Circle vs. Van Ness vs. Fort Totten vs. Union Station in DC shows that small blocks, a variety of building sizes, mixed uses, walking-based communities have much better success integrating and leveraging the value of transit.

Leinberger called the Green Line the next Red Line in terms of its impact. I don't agree with him fully because most of the stations do not have Walking City-Transit City era urban design, which makes it difficult to leverage the value of the transit. Even Petworth is tough beyond the immediate area around the Metro station, because the blocks are long and the intensity of residential development is relatively low. By comparison, Fort Totten really shows this. And then by building stuff that looks so junky, it's not likely to change.

Takoma is an interesting contrast to Fort Totten. While some of the infill residential construction looks great and some doesn't, there is already an albeit small commercial core, some restaurants and other amenities exist and more are coming as residential density increases. But for the most part, the Greater Takoma area has an urban form more conducive to walking and transit. It's not perfect, but it's better than Fort Totten at the subway station, and this will only increase over time. (But compared to stations in the core of DC, the area around Takoma/Takoma Park isn't densely developed in terms of residential population, which accounts for the relative weakness of the commercial district.)

But PG, other than further intensity of land use at the PG Plaza station, hasn't been able to leverage the value of transit because the stations are mostly placed in areas where they are disconnected from other uses, especially residential, not connected to it, and they don't evince "urban" design, but suburban, car-centric land use planning. The area around the PG Plaza station is still developed in a suburban form, it's just developed more intensely.

Anyway, Leinberger says that in advance of opening a transit system, you should have station area plans, covering 100-300 acres around the station, allowing for more intensive development. For the most part, I agree with him, but I think that examples thus far demonstrate the necessity of a fine grained urban design program for these station area plans.

A station area plan, in and of itself, may be good or bad. It's the good, fine-grained urban form plans that we need. Fort Totten and Rhode Island stations in DC shows that just because a subway station is "in the city" it won't necessarily be developed in an urban, rather than a suburban, fashion.

Rhode Island Place shopping center adjacent to the Rhode Island Metro station, northeast DC.

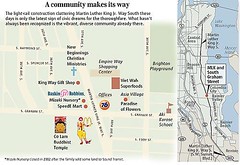

This weekend we had a house guest from Seattle, and she asked me what I thought about the impact of the forthcoming light rail line in Seattle, especially on the Rainier Valley. (See "MLK Way: More than a highway or a piece of the next grand plan, it's home" from the Pacific Northwest Magazine of the Seattle Times.)

Light rail construction on Martin Luther King Jr. Way South, Seattle. Seattle Times graphic.

I said it depends. That you need a system (DC has 5 subway lines, not one line) and then how the land is developed or exists around the stations really matters. If it's not developed in a coordinated, more intense fashion, the value of transit proximity is never fully captured.

The article on Vauban shows how a development needs to be designed to maximize the benefits of walking and transit, and not having to be car dependent.

Labels: sustainable land use and resource planning, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home