Planning for transit lines: trip speed vs. access and station density

There is an article in the Los Angeles Times, "Metro urged to add a Leimert Park stop on the Crenshaw Line," about how the Leimert Park neighborhood is advocating that a transit stop be placed in their neighborhood, as part of the planning and construction of the proposed Crenshaw Line. (Also see an entry from last fall, "Loan Generates Cautious Optimism" from the Fix Expo Line blog.) From the article:

... to dismay of some in South L.A., a new light rail line set to run through the heart of L.A.'s black community does not include a stop at the historic district. Instead, planners want to build a station about half a mile north, at the Crenshaw-Baldwin Hills mall, which they believe is more of a draw.

Construction of the Crenshaw Line is expected to begin next year, but some community leaders and residents are making a last-ditch effort to secure a stop in Leimert Park. They argue it's the right thing for the community and would make Leimert Park Village even more of a cultural draw.

"Leimert is its own special place. You cannot have a station at Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and a station at Slauson [Avenue] and not have one at Leimert," said attorney Nana Gyamfi, who lives in South L.A. and likes to hang out and shop in the village. "That doesn't even make sense to anyone that knows anything about the area."

But Metropolitan Transportation Authority officials are dubious, saying the station would add about $148 million to the $1.7-billion project and serve only about 840 riders a day. The Crenshaw Line is already $80 million over budget.

Roderick Diaz, the project director for the Crenshaw Line, said adding a stop would also violate a longtime Metro practice of not having stations less than a mile apart. (The rule has been broken before, as on the Expo Line near USC and on the Purple Line near Wilshire Center.

I've actually passed through this commercial district. It's been touted as an example of a Main Street commercial district revitalization program in an African-American community, and has been written up, in 2006, in the Washington Post, "Los Angeles's Black Pride." From the article:

This residential neighborhood and the small village at the center of it sit in the midst of Los Angeles's sprawl, seven miles southwest of downtown. It's one of the country's last strongholds of old-style African American culture and activism, with the happening ethnic flavor of Washington's pre-1968 U Street corridor. A world away from glitzy Hollywood and Beverly Hills, Leimert Park has a following that is solidly loyal, and apparently growing. A village Kwanzaa festival in December drew throngs of celebrants into the streets. Lively bongo drum jam sessions held in Leimert Plaza Park every Sunday are a major scene. Every weekend, fans of jazz or blues pile into the World Stage and other neighborhood music venues.

I have to say that I found the commercial district somewhat grim, then again it was during the day during the week, without any special events of any kind.

There is no question that the area can use the kind of revitalization energy that can come through improved access to heavy rail transit. Not to mention the benefits of increased access to more parts of Los Angeles via higher quality transit.

The importance of transit station density to the success of transit-related economic development and urban revitalization is discussed extensively in the book Cities in Full by Steve Belmont--note that I think this is the best book in urban planning since Death and Life of Great American Cities. It promotes the thesis of focusing land use and transportation planning paradigms back towards compact development, and the first chapter, very long, provides numbers to back up JJ's thesis about the importance of density to healthy cities.

From the standpoint of planning transit lines and stations, the question becomes one of speed vs. access. A line is faster if there are fewer stops. However, a transit system is more useful to potential riders based on the number of places that they can reach in a reasonable--not necessarily the fastest--amount of time.

Belmont criticizes most "new" (systems developed in the 1960s-1980s) transit system development programs as focused on polycentric development--enabling sprawl--rather than on intensifying land use and better linking residential areas to employment and other activity centers.

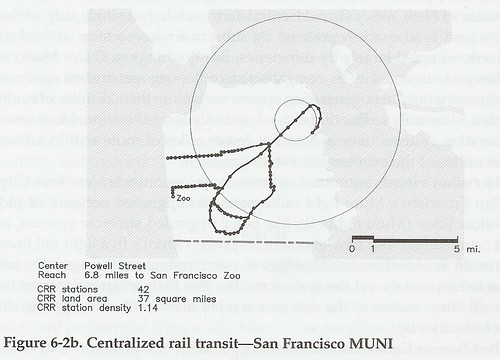

Belmont contrasts the BART system--which functions more like a commuter railroad for the SF Bay area--to the MUNI system in San Francisco proper. The former is polycentric, the latter monocentric. He criticizes the design of the WMATA system in DC as being polycentric as well, and not really reducing sprawl or inducing compact development at outer stations of the system.

Probably the only thing that Belmont missed in his analysis, at least of DC's transit system, is that the system doesn't function the same way across the entire network.

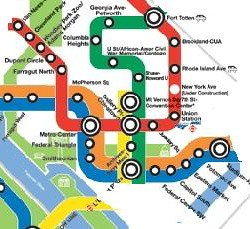

Station density is key to spurring economic development from transit. Specifically within DC's core, where there are 29 stations over a roughly 15 square mile area, the heavy rail system functions monocentrically, at least for DC residents. And this is the area of the city experiencing the most intensive revitalization and the construction of new housing and other mixed use developments, as well as the increased demand for pre-existing housing stock. It's happening in the areas served by transit stations all across this area--NOT ONLY DOWNTOWN.

Perhaps this is the most important still unlearned lesson that needs to be understood from observation of the success and failures of heavy rail transit in the Washington, DC region--the lessons are all around us.

Note that Arlington County has 4 stations along the Wilson Blvd. corridor over a 2 mile distance. DC has three stations along a similar distance, from Capital South to Potomac Avenue. In each case, the placing of stations was based on the land use characteristics of the neighborhoods and activity centers along the proposed route. It wasn't based on some arbitrary criteria of having stations no closer than one mile apart. These areas, relatively speaking, are thriving, although in both cases it has taken quite some time for most of the residential and commercial areas within the transit station catchment areas to catch up. (E.g., infill new construction in the Eastern Market and Potomac Avenue station areas is a more recent phenomenon, and it's making a big difference in the success of the neighborhoods in terms of adding population and new retail.)

Subway stations at the core of the city of Washington. Note that while Fort Totten is depicted on this map, it is not one of the stations that I term "core".

Similarly, Arlington County shows the wisdom of locating the Orange line along Wilson Boulevard rather than in the median of the I-66 Freeway. The four stations from Courthouse to Ballston have spurred billions of dollars of new investment and population increases--remember that Arlington County, like most inner ring suburbs, was losing population before the subway system opened--with the region's lowest tax burden (burden is a technical term here, I am not criticizing paying taxes).

The lesson then is that station density, at least in core areas of the system, needs to be provided, in order to have the kinds of multiple positive impacts on community that everyone says that ought to be reaped from transit investments.

Because this kind of lesson is only just being understood--in one of these reports, The Hiawatha Line: Impacts on Land Use and Residential Housing Value or Transportation as Catalyst for Community Economic Development, from the University of Minnesota Center for Transportation Studies, I recall the statement that the greatest benefits from transit investment come from the first 10 miles of the system, whereas I would argue that the greatest benefits come from areas of station density within a transit system, and it happens to be that the first 10 miles are where such station density is likely to be the most pronounced--many transit networks (such as the one in Denver) that are being developed are being planned polycentrically, and aren't likely to have the same kind of impact that has been experienced in DC and Arlington County (and to some extent certain parts of Montgomery County).

Note that the Transportation as Catalyst for Community Economic Development report has a robust framework for high-quality transit line and station planning and decision-making.

Sadly, this lesson hasn't made its way to Los Angeles (which is one of the study areas within the report), as the polycentric approach and the emphasis on speed over access appear to predominate transit line and station planning decisions there.

Proper station placement is key as part of getting station density right. There is more worthwhile discussion about how much it matters where stations are located, and this is a subtly different question from the station density factor.

Proper placement of stations is crucial to whether or not stations are successful in terms of transit as well as in terms of spurring economic development. Both the DC and Baltimore areas are replete with examples. (Because I write about this wrt Baltimore so often, I won't belabor the point here).

Two examples. First, many of the stations in Montgomery County, such as Bethesda, Rockville, and Silver Spring, are located in town centers, while stations in Prince George's County are not located in town centers. This contributes to the relative success of transit stations in Montgomery County, while PG County still touts itself--mostly to no avail--as a great place for transit oriented development.

Second, the City of Alexandria is served by two stations, Braddock Road and King Street, which don't directly serve core commercial districts. While the area around the King Street station has intensified because of the transit station, I think it would be the case that the Alexandria commercial district would be better off if a station served it directly.

Robust station planning is necessary to leverage proper station placement. The third overall element is the right kind of station planning needs to be in place, in order for transit investments to be fully leveraged. Because this entry is already over-long, I won't belabor this point.

But once you have the line in the right place, it's part of a transit network, with decent station density and proper station placement, then you need to have the right zoning and building regulation framework in place for surgically adding density to take advantage of the transit investment.

DC offers some examples of this, and I must note that 3 of the 4 examples have been very contentious within the neighborhoods.

1. Columbia Heights intensification, including the development of the DC/USA retail center. Note that I was against DC/USA originally--I was wrong by the way overall, but right about the over-provision of parking--even though I would argue today that as a single use project it left some opportunities on the table, although it has been complemented by horizontal mixed use projects that are very successful. Discussions in this neighborhood about change over the last year are still incredibly contentious.

2. Petworth intensification--ongoing. I haven't lived in this part of the city for very long, but I don't recall much opposition, which is the only example I can think of. While in the past 4 years, Columbia Heights has been DC's poster child for transit-led revitalization, I think Petworth will be the next poster child.

3. Tenleytown. Various intensification proposals at this station and between this station and Friendship Heights Station along Wisconsin Avenue have been fought off. The redevelopment of the old Sears into a mixed use retail + housing building has been very successful.

4. New mixed use projects in Brookland--one on Catholic University property, others at the Brookland Metro Station, or near it--in Brookland, have been vociferously opposed, although the Brookland Station project on the CUA land is moving forward.

Other projects in Takoma and Fort Totten have been a mixed bag. Fort Totten will be undergoing massive redevelopment which should change the character of the area, and convert it from a more car-oriented place to a walkable community with retail.

Redevelopment proposed at the Takoma Station is still contentious and I think problematic. Some of the previous developments are excellent in terms of design, both inside and outside, but some are not. This is a problem with the current new development at Fort Totten as well.

Labels: transit and economic development, transportation infrastructure, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home