Repetitive motion: land use and transportation practice and policy should be different for cities and towns

Image from "Texas traffic signs draw attention to deaths on road: Traffic deaths, safety messages will be displayed on Texas highways" from KFOX-TV, Austin, Texas.

This photo reminds me I've been meaning to write once again about how land use context and traffic engineering policy and practice, needs to be context sensitive, with one policy for cities and another policy for suburbs.

In cities, the transportation and traffic engineering policy should be focused on accessibility and safety and balancing conflicting requirements of pedestrians, transit users, and bicyclists vis-a-vis cars, and pedestrians vis-a-vis bicyclists, but with the focus on sustainable transportation.

In short, traffic engineering policies in cities shouldn't be focused on making motor vehicle traffic flow as unhindered as possible. Accessibility is the mobility concept that focuses on connections, about being able to get to and from places efficiently, rather than congestion per se. In a city, accessibility is achieved differently than in suburbs, mostly through proximity--home, work, and leisure activities all relatively close.

This came up on a listserv I'm on, where people were talking about what they thought was "shared space" but was really the consequence of "no/bad" design in Northampton, Mass., where the roadway is extremely wide--probably because back in the day horse-drawn wagons needed to be able to turn around--and these days because motor vehicle drivers don't know how to proceed, they drive slowly, making it a bit better for pedestrians to cross the street in the context of traffic.

Another example that was called shared space is Massachusetts Avenue near Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and how because there are so many (student) pedestrians, cars yield.

But the reality is that isn't "shared space" so much as it is "pedestrian-dominated" space because in that area, people on foot are the majority. Note that in my experience going to college in Ann Arbor, the streets abutting Central Campus operated similarly--pedestrians dominated and cars stopped if you walked out in the middle of the street. But I learned when I moved to DC that this is an uncommon practice.

And while the point of shared space design concepts is to balance conflicting concerns of motor vehicle traffic with pedestrian and quality of life concerns, basically allowing cars into walking prioritized areas, this point of pedestrian-transit-biking dominated areas vs. motor vehicle dominated areas is key.

While there is no question that traffic is getting a bit worse as DC's population increases, the reality is for the most part, with transit, walking, and biking all serving as significant transportation modes, traffic isn't that bad, and at least in the core, it's easy to get around. (Outside of the core, biking is required to maintain accessibility from a sustainable transportation perspective.)

Rather than make over all areas for automobile supremacy, we need to acknowledge the differences (walking-transit city spatial patterns vs. motor vehicle spatial and mobility patterns) and plan and build infrastructure accordingly.

This extract from a job site ad in the New York Times is a good illustration of the concept of accessibility, and how "the ability to reach ... destinations is affected by many factors, including the transportation infrastructure, travel behavior preferences, patterns of land use and development, availability of mass transportation services, and traffic management policies" (UMN Access to Destinations website) and doesn't have to be dependent on a motor vehicle.

This means transit priority, biking infrastructure, high quality pedestrian infrastructure, and road paving materials (asphalt block etc.) that contribute to reductions in motor vehicle speeds. And signs at the entry points to the city ought to stress that unless posted otherwise, the speed limit is 25mph.

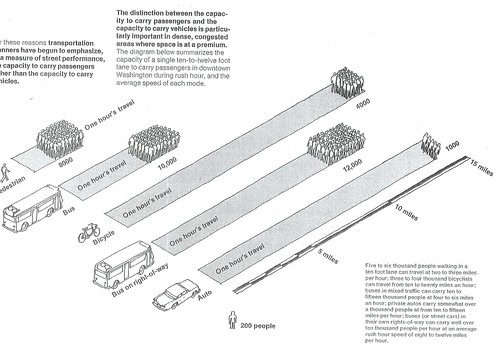

Mobility efficiency in Washington, DC. From the Central Washington Transportation and Civic Design Study, 1977.

Moving from one mobility paradigm to the other is very difficult. And it's not simple either.

A lot of opposition to the reintroduction of fixed rail transit comes from people being imprinted so strongly with an automobility-centric land use and transportation planning paradigm that they can't imagine middle and upper class people choosing to ride transit willingly.

A lot of opposition to the reintroduction of fixed rail transit comes from people being imprinted so strongly with an automobility-centric land use and transportation planning paradigm that they can't imagine middle and upper class people choosing to ride transit willingly. They see transit mostly as a social service for people who can't afford cars.

This comes up in the comments on an article, "The tide, one year later" in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot about the Tide light rail system there, and discussions about extension in the context of a nonbinding referendum this fall on the Virginia Beach ballot, to gauge voter support (which could be scuttled by something else, regional animus over the State of Virginia's plan for tolling the Midtown Tunnel to build another tunnel, see "Tolls, tolls, tolls. How did we get into this mess?" from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot).

Oddly, opposition can be a problem in places already served with heavy rail.

We see opposition to streetcar reintroduction in DC and Arlington County--communities that are best practice examples for successful subway service and its positive impact on focused land use intensification and neighborhood revitalization, and for light rail introduction (the Purple Line) in Montgomery County (for the most part, opposition hasn't surfaced to the Purple Line in Prince George's County). Most of the opposition is by motor vehicle drivers, who argue in part that choice riders will willingly ride buses.

If you have problems promoting extension and expansion in places where fixed rail transit service is already successful, imagine how difficult it must be in places where it isn't already present.

Although having a transit network as opposed to a line or two is necessary to bring about the kinds of real and positive changes that are so evident in DC and Arlington County. And to reduce the actual number of motor vehicles on the roads.

So it is really two very distinct and different spatial patterns and land use contexts that we need to plan for, while transportation planning has been focused on automobility and traffic engineering is focused on securing and maintaining traffic flow for motor vehicles.

Not that this is anything new, but obviously this point must be repeated and emphasized frequently, because it is so counter to the prevailing attitudes and beliefs that people have about what is appropriate policy and practice for mobility and land use.

Labels: car culture and automobility, sustainable land use and resource planning, transit oriented development, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home