The market is driving neighborhood change (displacement) and changing the zoning code won't have any effect on that

Someone asked me about "Gentrification and Displacement" in the context of the proposed new Zoning Code in DC, which will "overturn" the 1958 Code, which is suburban in intent and oriented to separated uses, in favor of something more urban and more smart.

The proposed code will be passed in sections, each of which will go through a hearing process. Some of the proposed provisions, such as eliminating parking requirements for new construction in areas that are well-served by transit, or simplifying the ability (I still have problems with many of the proposed provisions) to create accessory dwelling units on properties (carriage house type units) have enraged numbers of DC residents.

Last week there was a hearing about this at City Council (see "Mendelson wades into the zoning update with Sept. hearing" from Greater Greater Washington) where arguments counter to the proposed change to the Zoning Code "Philosophy" were proffered.

Anyway, here was my response [slightly edited]:

Left: rowhouses in Bloomingdale, probably dating from the 1890s. The inventory of such housing is relatively fixed.

Left: rowhouses in Bloomingdale, probably dating from the 1890s. The inventory of such housing is relatively fixed.in 2007, I was like the 3rd person who testified at the first zoning commission hearing on whether or not to update the code. When Carole Mitten [the then Chair of the Zoning Commission] asked what we thought of the code and whether or not it works, George Clark [then the president of the DC Federation of Civic Associations] said it was great, and I said, "the number of overlays and requests for overlays is an indicator that the code isn't working, and doesn't generate the kinds of outcomes that people are looking for."

(Now I talk about this issue like this: "the point of planning and zoning is to improve quality of life. When outcomes from planning and zoning processes don't do this routinely, we need to look backwards at the policies, codes, and regulations and figure out what isn't working, why it isn't working, and change the processes so that positive contributions to quality of life become routine outcomes.")

In my opinion, most of the people in favor of the current code prefer it because it's predictable and they know how it works, but they don't really think about the negative impact of many of its provisions on the city. It's not designed for a center city, but for the suburbs.

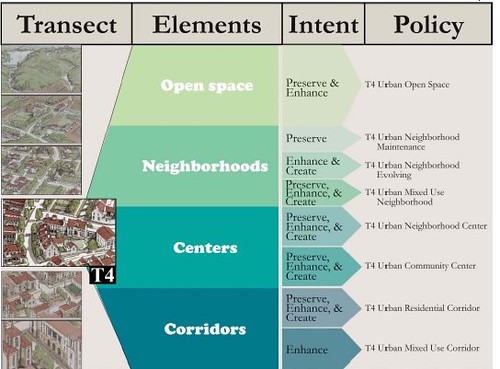

wrt the code, I argued that the "new code" should be based on the framework of the Nashville Community Character Manual. It's based on the SG "transect"--6 land use contexts, from rural to dense urban--but has a number of subcategories for each transect "zone" depending, e.g., residential, commercial corridor, etc.

That would provide, in my opinion anyway, a much finer gradient for zoning better fitted for more particular land use contexts than an overall "general zone" approach or the "let 1,000 flowers bloom" approach I've heard about that will let every neighborhood create their own overlay, but only after the new code is approved.

Every neighborhood doesn't need it's own overlay. Most concerns can be accommodated in the more fine grained approach to zoning offered by the NCCM.

Above: this diagram from the NCCM outlines 8 different types of land use for the T4 land use context. T4 is defined as the "general urban zone." In DC, it is primarily residential, but is punctuated with mixed use (or at least, retail uses) in commercial strips that may be a couple blocks long (like the little cluster of shops on Upshur Street in Petworth), as a more tightly connected "commercial district" (like Old Town Takoma, which in the DC context, is actually in Maryland) or in long strips along arterial streets (like Georgia Avenue).

Right: this visual rendition of "the transect" comes from the childrens book, The House Book, by Keith DuQuette. (Although it doesn't really show T4 so much as jump from T2/T3 to T5.)

The Office of Planning actually explored this approach (at my instigation) but they ended up rejecting it, believing that the Advisory Committee would find it to be too radical.

That being said, displacement and neighborhood change (I don't like the G--gentrification--word) is going to happen, and happen big time, whether or not the zoning code is changed.

It's a function of the color green--money--and housing choice trends that favor cities -- money and the market -- and doesn't have much to do with bringing "old urbanism" back, other than that cities are more likely to allow people to live carless or car-lite and get around by walking, biking, and transit.

The reality is that "Smart Growth" development principles are, historically, the same kinds of development principles that were applied in the city, even as the city expanded outward at least through the 1930s and early 1940s, e.g., as discussed in the now out-of-print DC Office of Planning publication Trans-Formation: Recreating Transit-Oriented Neighborhood Centers in DC: Design Handbook.

The reality is that "Smart Growth" development principles are, historically, the same kinds of development principles that were applied in the city, even as the city expanded outward at least through the 1930s and early 1940s, e.g., as discussed in the now out-of-print DC Office of Planning publication Trans-Formation: Recreating Transit-Oriented Neighborhood Centers in DC: Design Handbook.The other way to think about this is in terms of the walking and transit city eras of city development, such as that described in this webpage about the change in cities that came about as walking and transit were replaced by the automobile as the dominant mobility mode in the United States.

Backyard garage between R and S Streets NW on the north side of Connecticut Avenue. By adding a floor, buildings like these could easily add to the city's housing stock as rental units, providing lower cost housing options, housing close to transit service, and additional income for property owners.

I argue for the addition of mixed use residential to commercial districts and for ADUs, because I think that's a way to accommodate additional population (which has a lot of benefits, the city's increase in population is one reason why some neighborhood commercial districts are starting to improve after languishing for decades) without significantly changing neighborhoods.

One problem with monoculture residential zoning is that neighborhoods aren't very resilient and aren't very good at maintaining the inclusion of households at different income levels.

As urban neighborhoods become attractive, people with money will always be able to outbid people of lesser means, hence "gentrification."

Right: the Ellington Condominiums on U Street NW.

Especially because the city's housing supply, at least of single family detached and attached (rowhouse/duplex/triplex/flats) is pretty much fixed, with some exceptions (for example rowhouses by EYA in Brookland, being marketed by ads such as the one above, or Pulte at Fort Lincoln etc.) the city really only has the ability to add multiunit housing.

And it does this not by tearing down existing housing or residential neighborhoods, but by building multiunit housing in commercial districts or at subway stations.

To deal with displacement requires policy tools other than zoning as it's a phenomenon that is mostly a function of markets and property tax policy (as long as property tax assessments are a function of the current value of the property, in rising markets people of lesser means will eventually be priced out through rising assessments).

Labels: land use planning, protest and advocacy, sustainable land use and resource planning, transit oriented development, transportation planning, zoning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home