This is an update of a piece from 2007, which I decided to incorporate into this series

-- "Basic planning building blocks for urban commercial district revitalization programs that most cities haven't packaged: Part 1 | The first six"

-- "Basic planning building blocks for urban commercial district revitalization programs that most cities haven't packaged: Part 2 | A neighborhood identity and marketing toolkit (kit of parts)"

-- "Basic planning building blocks for urban commercial district revitalization programs that most cities haven't packaged: Part 3 | The overarching approach: destination development/branding and identity, layering and daypart planning"

-- "Basic planning building blocks for "community" revitalization programs that most cities haven't packaged: Part 4 | Place evaluation tools"

=========

I mention from time to time my belief that neighborhoods should create their own plans, or at least, develop a systematic understanding of their places, in order to be proactive.

Here are some survey forms and tools that structure how I think about and approach assessing purposes.

Place assessment tools

1. The Problem property audit form pictured above was created by researchers at the University of Memphis to evaluate declining neighborhoods. It's not online any more. There are probably other ones out there.

2. NYC Business Improvement District Needs Survey

3. The Project for Public Spaces Place Game, which they have used with individual businesses in a commercial district corridor in places like Littleton, New Hampshire. It's a fundamental tool in the PPS manual, How to Turn a Place Around, which has been recently updated in a second edition. I highly recommend the book, and sometime this year will write up a review.

Combining the NYC form + the Place Game approach business-by-business should be a basic requirement at the outset of creating commercial district revitalization programs.

4. Litter Survey Form from Keep Australia Beautiful (adding a couple things makes this an excellent overall public space evaluation tool -- gum and other markings on sidewalks, graffiti--on street signs and buildings, and signs posted in the public space). I find this tool more detailed than similar items from US-based organizations.

5. Open space survey tools such as the Community Gardening Survey Form from the Garden Mosaics program at Cornell University.

Assessing the quality of development proposals

6. Urban Design Evaluation Tool & Glossary of Terms from the Design Advocacy Center (Philadelphia)

7. Community Design Assessment: A Citizens' Planning Guide from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Sadly, NTHP, believing no one reads anymore, discontinued their publication program. They had a deep catalog of worthwhile manuals and books on all topics of preservation. It was a criminal decision.

Fortunately I took a photo of the survey form.

Placemaking/Destination Development/Tourism Assessment

8. Dan Burden's "How Can I Find and Help Build a Walkable Community" and "The 20 Ingredients of an Outstanding Destination" by Roger Brooks International, and the PPS Place Game and How to Turn a Place Around but focused on the overall place.

Creating Great Places/Destinations, Project for Public Spaces.

9. While updating this piece, I came across a great resource called the Placemaking Assessment Tool produced by Michigan State University Land Policy Institute. It distinguishes between four types of placemaking: standard; tactical; creative; and strategic, and provides two different assessment tools (one for the first three; one for the fourth), which are quite detailed and remind me of

10. the out of print Tourism Destination Assessment Workbook from the Nova Scotia Department of Tourism. Back when I first wrote this piece, I thought it was a great way to shape my thinking about destination development. There are many other such examples that aren't out of print, including the various worksheets in Nova Scotia's updated Community Tourism Planning Guide.

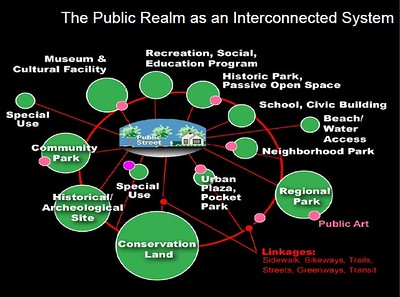

11. David Barth. I heard him speak first in 2004 and it really influenced me. Then he was trying to marry the best of parks planning principles, New Urbanism, and certain City Beautiful concepts in what he called "City Revival." Later I came across a presentation on the "integrated public realm framework" that propelled and illustrated my thinking about civic assets as networks.

Now he focuses on "High Performance Public Spaces: A Tool for Building More Resilient and Sustainable Communities" (ASLA The Field blog). Grouped in terms of economic, environmental, and social return, the evaluation tool looks at 25 elements to determine how well spaces can perform.

12. John King is the urban design writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. In 2005, he wrote "Great architecture, clean streets, culture -- it must be Minneapolis," listing ten elements of great cities:

1. Street life thrives if you give it a chance.

2. Convenience isn't nearly as convenient as it seems.

3. The more [things to do] the merrier.

4. Culture adds spice.

5. Narrow streets are better than wide ones.

6. Play up the local angles.

7. Good architecture is good architecture, no matter the style.

8. Change is good.

9. Cleanliness counts.

10. Women know best.

Transportation Resources

(I didn't include transportation planning tools in the original list)

13. There are many including Pedestrian Road Safety Audit Guidelines and Prompt Lists, Pedestrian Safety Guide and Countermeasure Selection System and Bicycle Safety Guide and Countermeasure Selection System, all produced with the support of the Federal Highway Safety Administration.

14. School Walk and Bike Routes: A Guide for Planning and Improving Walk and Bike to School Options for Students, Washington State DOT. Making places great for walking and biking to school makes them great for everyone else.

15. Main Street: When a Highway Runs Through It, Oregon State DOT

16. Smart Transportation Guidebook: Planning and Designing Highways and Streets that Support Sustainable and Livable Communities, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission

17. This doesn't look at transit stations, just bus stops, Transit Waiting Environments (out of print). Network Rail has produced a good manual for rail station planning that is applicable, Station Design Principles. And this SEPTA guide, Modern Trolley Station Design Guide. My written reviews as blog entries of the Silver Spring and Takoma Langley Crossroads Transit Centers provides an excellent framework, if I say so myself.

My own approach to evaluating residential and commercial districts

The other "tool" I use is based on work done for HUD in the 1970s, and used by most jurisdictions around the country. In a way it's pretty basic, you assess neighborhoods based on whether the neighborhoods are:

1. Healthy

2. Transitioning

3. Emerging

4. Distressed.

I think the researchers contracted by HUD came up with 5 categories. Philadelphia uses 6. DC 4--although they don't necessarily use the same terms to classify neighborhoods. Charles Buki uses 3 categories. Basically the difference in the number of rungs on the ladder depends on whether you break the basic four rungs into "high"--transitioning to the next rung, and "low" differentiations within each rung category. So you can have as many as 8, with high and low in each.

I think this works at the scale of the neighborhood and district, for example you can compare a large neighborhood in a big city to the Downtown of a smaller city, etc.

But, you need to do three other things alongside this, which most places (including DC) don't do:

1. Evaluate separately and simultaneously the commercial district and the residential parts of the neighborhood -- your ability to move the commercial district up the ladder is dependent on the density and economic capacity of the residents.

Typically commercial districts lag residential areas. So when investment is put into the commercial district in these situations, the improvement can be seemingly quick.

And past community development strategies--building better housing for poor people--didn't improve the commercial district, because for the most part the micro-economy of the area remained unchanged (see the Community Economic Development Handbook by Temali).

2. You can also use the general criteria to evaluate places block-by-block as well, to help develop more focused strategies for specific needs.

3. Overall, cities should develop differential policies for places based on this criteria, both at the district and block scales.

Point (3) is crucial and the cause of most failures in government policies and programs. By creating one size fits all programs, and not really understanding the nuances and details of a place, and the levers at your disposal, failure is much more likely.

E.g., emerging and distressed commercial districts aren't likely ready for street furniture, and need more assistance in developing organizational capacity, compared to healthy districts, or those in later stages of transition. Similarly, it's much harder to move distressed commercial districts up the ladder when the residential neighborhood is also distressed.

And speaking of credit, Rachel MacCleery, the then Ward 6 Transportation Planner (now at ULI), and I figured this out together, that commercial districts and residential areas need to be separately and simultaneously evaluated, in order to figure out the likelihood of success.

We were trying to figure out why the investment in streetscape improvement "worked so quickly" on Barracks Row -- 8th Street SE. Most people don't really understand that the success there isn't merely a function of the investment, but in the overall condition and economic capacity of the greater neighborhood (within which the investment was made).

Because much of the property in our commercial districts has absentee ownership, improvement in commercial districts tends to lag improving residential areas, unlike the impact of residential improvement on other building owners (see Building Neighborhood Confidence and Understanding Neighborhood Change both by Rolf Goetze, for more insight into this process).

No comments:

Post a Comment