Tysons (Corner) is about 5 square miles and now has about 20,000 residents. According to the Tysons Partnership, by 2050, it's projected to have 100,000 residents and a few hundred thousand jobs. As the book Edge City pointed out, it's the equivalent of a Downtown except that it's much more spread out, and with an urban design oriented to cars not people.

In the previous post I didn't address why it is significantly more difficult for the Metrorail line to repattern land use in Tysons the way it did in Arlington County, along the Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor, or in Downtown DC.

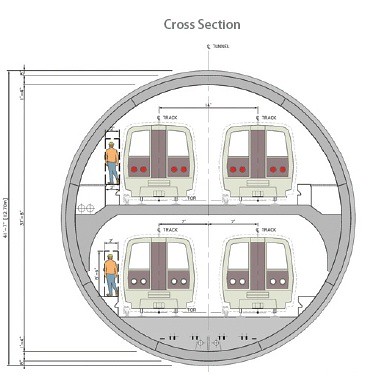

The first has to do with the unwillingness by the State of Virginia to pay extra to underground or tunnel the line.

The first has to do with the unwillingness by the State of Virginia to pay extra to underground or tunnel the line.This was a big issue during the planning phases of the line (the other was the station being closer at Dulles Airport). There was an advocacy effort, Tysons Tunnel, with the aim of shifting the decision to a tunnel, but it failed.

It's a lot harder to change land use when a heavy rail line is at or above grade. Often there are right and wrong sides of the tracks. The tracks are a divider and the trains are usually noisy.

It costs a lot more, but you see with places like the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor in Arlington County or Downtown DC that there is tremendous economic benefit that more than pays for the additional cost.

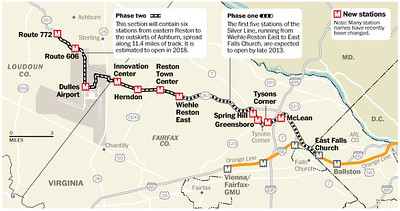

The second has to do with the number of and distance between stations. In Arlington County, while it is 1.1 miles between Rosslyn and Courthouse Stations, from Courthouse Station to Clarendon to Virginia Square to Ballston is four stations over two miles.

Significantly, the original design for this stretch of Metrorail was for it to be located within the I-66 freeway median.

Instead, the County then in decline and experiencing population loss like most inner ring suburbs at the time, realized that by shifting the Metrorail line to Wilson Boulevard they could change their economic trajectory.

By contrast, the Metrorail in Tysons follows the equivalent of a freeway--a very wide arterial, with stations located within the median, making the stations incredibly difficult to access and difficult in terms of repatterning land use. There are four stations, about 3 miles from McLean Station to Spring Hill Station, with Tysons and Greensboro Stations in between.

Silver Line station map. Washington Post graphic by Gene Thorp.

This idealized Metrorail graphic by Eric Fidler also shows the forthcoming Purple Line light rail.

By contrast, in Downtown DC/the Central Business District there is a comparatively large number of stations serving an area a bit larger than Tysons (from Farragut North to NoMA on the Red Line, from GWU to Capitol South on the Blue/Silver/Orange Lines, Mount Vernon to L'Enfant Plaza on the Yellow line and to Navy Yard on the Green Line totals 18 stations--although the Smithsonian Station doesn't serve the business district). This is because rather than there being one single linear line serving the area, there are multiple, crossing lines that intersect.

This graphic, a subsection of the Metrorail "map," is the foundation of what I call the City of Washington's primary transit network, and the stations serving the Central Business District are a further subset of this. (Later I redefined this subset to include the Waterfront and Navy Yard stations on the Green Line, to reflect new and intensive (re)development of those areas within the Southwest Quadrant.)

This set of stations acts monocentrically, intensifying development within the area, which is complemented by a center city grid of reasonably sized blocks which support and preference sustainable modes--transit, walking, biking and other forms of micromobility--rather than the automobile.

Bus service including a city-provided Circulator system independent of the Metrobus network complements the underground subway network, but it isn't prioritized (dedicated bus lanes are being deployed) so it's slower.

For Arlington, circulator service isn't an issue, because the R-B corridor is linear, focused on Wilson Boulevard, and the intensely developed section doesn't extend more than a few blocks on either side. Tysons is not a linear district, it sprawls over a 5 square mile area. (Arlington's transit access and connectivity issue is inadequate connections between North and South Arlington.)

Detroit People Mover. Photo: P&A Imaging, Kewsi Mann.

Intra-district transit and People Movers. If I were to pick out my 10 or 20 most significant posts, one would be on thinking about transit in terms of a network comprised of primary, secondary, and tertiary networks.

This grew out of my reading of the Arlington Master Transportation Plan, which c. 2005, was pathbreaking. It defined Arlington's primary and secondary transit networks, as complementary to Metrorail and Metrobus.

I extended these ideas cross-jurisdictionally, at much wider scales: regional; metropolitan; suburban; and center city, with subnetworks.

While I didn't integrate the concepts, in terms of the "tertiary" network, which includes what I call "intra-district" mobility, another top 20 piece, "Making the case for intra-city versus inter-city transit planning," distinguishes between inter-city (getting to and from) and intra-city (getting around within) mobility, and discusses various approaches to intra-district transit, one being people movers. (Also see "Intra-neighborhood (tertiary) transit revisited because of new San Diego service, 2016.")

(Intra-district transit isn't necessarily "tertiary" but can be elements of the primary or secondary transit networks, depending on district size, primacy, and the nature of the overall transit network.)

Most people come across people movers as an element of airport transportation, shuttles that operate between terminals.

There are three aerial people movers in the US in Downtowns, in Detroit, Jacksonville, and Miami.

While in those places the systems aren't super successful in terms of massive ridership, they do provide intra-district transportation on a wider scale within a central business district. By being above-ground, they are never stuck in surface traffic. And they are a lot less expensive than a tunnel-based system.

Miami Metromover map, by Houchou, from Wikipedia.

The Miami system connects to two Metrorail stations, has 21 stations, and more than 30,000 daily riders.

Thinking about this now, I'd argue that the casino-focused monorail in Las Vegas is more of a people mover than anything else, because it doesn't connect to other activity centers in "Las Vegas" like the Downtown or the Airport--it was designed to facilitate transit between casinos but not to let people "escape" casinos.

In reality, the monorail doesn't even serve the City of Las Vegas, but the Las Vegas Strip, which is not within the city boundaries.

Separately in Las Vegas proper, the newest mobility initiative is to have Elon Musk build some tunnels, which shows the failure to lay the foundation for a more robust transit system with the monorail. It's also not designed to move all that many people ("These Vegas casinos want Elon Musk’s Boring Company to build them tunnels, with Teslas to transport guests," CNBC).

It's really more of a boutique, toy-like service, albeit intra-district.

The High Line tracks in NYC when it was used as a freight railroad.

Other types of intra-district mobility networks that use either above-ground or under-ground paths are pedway (Chicago, Toronto, Montreal) and skyway (Minneapolis, St. Paul) networks, as well as the old underground freight transit system in Chicago, the High Line freight railroad in Manhattan, now repurposed as a park, and pneumatic tube systems for mail and other transactions.

Tysons ought to have considered an above-ground people mover for intra-district transportation, complementing underground Metrorail stations. (Although it can still be done even though the Metrorail stations are above-ground.)

If you define a city or a downtown as more than a collection of buildings, but an integrated and connected place, Edge Cities are conglomerations and conurbations, but they aren't cities or downtowns as much as they are "Concentrated Suburban Business Districts."

-- Ten Principles for Reinventing Suburban Business Districts, ULI

-- Ten Principles for Reinventing America's Suburban Strips, ULI

-- Ten Principles for Rethinking the Mall, ULI

Tysons is a concentrated area, but not a city in a true sense. And that's what the Tysons Master Plan and the Tysons Partnership is aiming to change.

To get the intensified effect on land use, and to maximize the ability to shift the land use and transportation paradigm away from automobile-centricity, the breakthrough idea would be for Tysons to create a people mover system for intra-district transit.

This would truly set the stage for transform Tysons to a city that is the Downtown for Fairfax and Loudoun Counties, rather than a large set of buildings on the edge of the core of the metropolitan area.

Again, while the Las Vegas Monorail is linear rather than circular, it's a model for what could be achieved, with a better vision and plan to enhance mobility throughout the Tysons district, rather than the more narrow focus on casinos in the Las Vegas Strip that marks the Vegas monorail.

Las Vegas Metrorail Map

The trick of course it to figure out how to do this cost effectively.

And I realize that in most circumstances, this would be a crazy idea. The suburbs don't have that level of density and intensity, as well as massive numbers of intra-district trips, to justify even thinking this way.

Long range development intensity plan for Tysons, Fairfax County, Virginia.

But there are a handful of exceptions in suburbs, yes in "Edge Cities" where this might be viable and worth implementing, including Tysons in Northern Virginia, Buckhead and Cumberland (where the Braves Stadium is) in Greater Atlanta, certain places in Dallas, the Houston Medical Center, maybe outside of Boston along Route 128, and place or two in the Silicon Valley.

Arg! Not this stuff again.

ReplyDelete"It's a lot harder to change land use when a heavy rail line is at or above grade."

This has nothing to do with Tyson's challenges. The barriers are Routes 7 and 123 and the traffic sewers they are.

Burying the line in Arlington was beneficial because Arlington had an existing pre-war street grid. Tysons did not, and thus the benefits to walkability from a tunnel are essentially nil.

The criticism I have is that the elevated stations should actually make it easier to have more station access points (unlike subway stations) and yet they've failed to take advantage of that.

Don't think it's either/or, more like and/and, but (as usual) you are absolutely right about Rtes. 7 and 123.

ReplyDeleteIn any case, this is about intra-district mobility, which by improving it, allows for even deeper intensification.

You can't really change the reality of Rtes. 7 and 123, which are regionally serving. Sure they bring people to and from Tysons, but their primacy extends far beyond Tysons.

And of course, why Tysons is where it is and was able to "embiggen" (a la Tom Tomorrow) was because of those roads, plus I-495.

Have you ridden the monorail in Vegas (assuming you have)? The ride quality is atrocious

ReplyDeleteHaven't. But I have ridden the one in Seattle. It was fine (very old of course).

ReplyDeleteWhat is that Tyson's tunnel cross-section supposed to represent? That is obviously not a station cross section, at least I hope not. Was there ever a proposal for 2 lines? I don't understand why this shows 4 tracks.

ReplyDelete