I mention frequently in posts that I am a big fan of the NHK World television program, "Japan Railway Journal," which has opened my eyes to rethinking how the US does passenger rail planning (although I still haven't gotten around to finishing-publishing my series of articles on the topic). (This channel is distributed by PBS stations throughout the country, but the show is also available online.)

Yesterday's program, "Securing the Future of Japan's Local Railways," focused on success strategies for the small railroads across the country, which complement the national and regional services by JR and certain other larger companies, mentioned a program I wasn't familiar with, the Toyama City Compact City revitalization program.

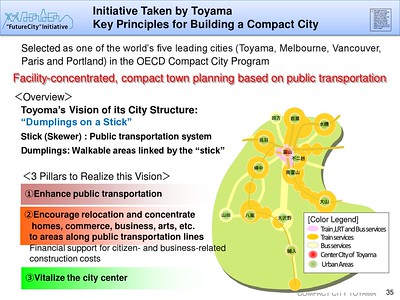

It's a perfect illustration of the point of using intra-district transit as a way to refocus development towards the core of the city (Development Knowledge of Toyama City, World Bank).

They undertook a number of transit-related measures: (1) they created a new locally-serving light rail line on a northern rail line abandoned by Japan Railways; (2) they connected the previously unconnected northern and southern transit lines; (3) allowing the more modern northern light rail vehicles to be used throughout the city, although the older vehicles remain in operation; (4) they created a loop line within the existing transit system to foster new development within the core of the city.

The loop line is an intra-district transit approach, which I have discussed in many posts including "Making the case for intra-city vs. inter-city transit planning" (2011).

It operates within the larger transit network.

Portland and Seattle. While the original post on intra-district transit programs references streetcars in Portland (Downtown and the Pearl District, since expanded) and Seattle (SoDo originally, since expanded), I can't believe I didn't mention Portland or Seattle as relevant examples in the Tysons post.

By contrast, I mentioned "people movers" in Detroit, Jacksonville, and Miami, the monorail in Las Vegas, and bus-based circulators.

Portland and Seattle are the ultimate US examples of using streetcars to foster development and intensity within the core of a center city.

Tysons isn't a center city, but as an edge city if it wants to develop a sustainable mobility paradigm, these are great examples, especially as it is a rare suburban conurbation that has the level of intensity necessary to support this kind of transit.

Since then, cities like Cincinnati, Kansas City, and Oklahoma City, Tucson, and to some extent Washington, DC ("Modern streetcars are transportation projects,not merely economic development augurs: but intra-district not inter-city services," 2017) have adopted similar programs, with varying levels of success.

David Eulitt, Kansas City Star.

A big problem is expansion, anti-transit forces fight funding proposals vociferously.

The OKC streetcar is one of the newest, and is equally relevant to Tysons. Oklahoma City is a center city, but sprawls over 500 square miles. It's a "suburban" city along the lines of the "Metropolitan City era" discussed by Peter Muller in "Transportation and Urban Form." For OKC, the streetcar is about strengthening and intensifying its core ("Oklahoma City's streetcar story is all about development," Daily Oklahoman;

"Oklahoma City Hopes for Lift From Downtown Streetcar," Wall Street Journal).

Tysons has exactly the same issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment