Time Magazine Picks the Five Best Mayors in the U.S.

In "The 5 Best Big-City Mayors:They rule over tough territory, yet offer strong examples of how cities can be efficient and livable", Time Magazine tells us that

"The best mayors in U.S. history have been great characters--showmen and radicals and bullies and rebels. Then again, so have the worst. Fiorello LaGuardia, who ruled New York from 1934 to '45, besides reforming and rebuilding his city, was famous for smashing slot machines with a sledgehammer and reading the comics to children over the radio during a newspaper strike. On the other hand, Chicago's William (Big Bill) Thompson, first elected in 1915, kept a picture of his good buddy Al Capone on his office wall and once conducted a debate between himself and two white rats, which he placed onstage to represent his political opponents.

It is tempting to judge our mayors for the little things that make city life livable, the depth of the potholes, the smell of the streets, whether or not the traffic lights are in synch. But the best mayors have also been those who act on a grand scale, building bridges, saving schools, finding the funds that cities forever lack.

TIME consulted with urban experts to choose the best among the leaders of America's most challenging cities, those with populations over half a million--a crop that brings in six Republicans, 22 Democrats and one unaffiliated mayor. That cutoff excluded mayors like Randy Kelly of St. Paul, Minn. (pop. 288,000), who has slashed crime 30% in 3 1/2 years. Our top performers range from Chicago's imperial Richard Daley, who after 16 years is widely viewed as the nation's top urban executive, to newcomer John Hickenlooper, the beer brewer who closed Denver's worst budget gap ever without major staff or service cuts. Since good policy invites imitation, their most successful tactics may soon be coming to a city near you." --By Nancy Gibbs

1. Rchard the Second: RICHARD DALEY / CHICAGO

He wields near imperial power, and most of Chicago would have it no other way. Two years ago, Richard Daley was re-elected to his fifth term with 79% of the vote. His annual budgets are routinely passed with only token opposition. He controls public housing, public schools and the city council. He is cozy with Big Business, is a master at the ward politics of fixing streetlights, and he speaks with a blunt, blue-collar brio that Chicagoans find endearing. "There's never been a [U.S.] mayor, including his dad, who had this much power," says Paul Green, professor of policy studies at Chicago's Roosevelt University. And he's used it to steer the Windy City into a period of impressive stability, with declining unemployment and splashy growth.

From the days of Daley's legendary father, sometimes known as Richard the First, Chicago's national reputation as a bare-knuckle city of backroom deals by the Democratic faithful and their labor-union allies has always held a lot of truth. But Daley has professionalized the city by hiring skilled managers and burnished its business-friendly image by strengthening connections to global firms like Boeing, which relocated its headquarters to town, and to white-shoe industries like banking, financial services and law.

In his 16 years at city hall, Daley, 62, has presided over the city's transition from graying hub to vibrant boomtown, with a newly renovated football stadium, an ebbing murder rate, a new downtown park, a noticeable expansion of green space and a skyline thick with construction cranes. As federal and state dollars flowing to the city have dried up, he has used his influence to persuade corporations and the wealthy to kick in for big-ticket attractions, like the $475 million Millennium Park, nearly half of which was paid for by private donations.

Daley's unchecked power sometimes short-circuits public debate. In 2003, under cover of night, he unexpectedly dispatched wreckers to demolish Meigs Field, a tiny downtown business airport that he called a security risk but preservationists had been fighting to save. Allegations of financial corruption have caught up some of his political allies, although Daley has personally avoided implication.

With so much political capital at his fingertips, the mayor has been able to take big risks. The city is in the midst of knocking down its old high-rise housing projects, which concentrated the poor in pockets of crime and privation. Many of the former tenants are being relocated to better, low-rise housing that blends into existing neighborhoods. Since Daley took over the school system in 1995, he has brought graduation rates up from 51% to 54%, but he's not stopping there. Last year he launched a reform plan in which old, failing schools are to be replaced with new ones that have more autonomy over their curriculums. So far Daley has $24 million in private commitments to fund the program. The best way to minimize crime and poverty in a city, Daley believes, is to keep the middle class from fleeing to the suburbs. "Education is the complete answer to all these other social issues," he says. "The key for all cities is whether you turn public schools around."

Even with his success, few see Daley moving beyond the mayoralty to a higher office. "This is not a job for him. It's a calling," says local political consultant Kevin Conlon. "He's mayor as long as he wants to be." --By David E. Thigpen/Chicago. With reporting by Eric Ferkenhoff

2. Restorer of Faith: SHIRLEY FRANKLIN / ATLANTA

Shirley Franklin isn't standard mayor material. For starters, she's a woman, which makes her the first female mayor Atlanta has ever had; in fact, she's the first black woman ever to run a big Southern city. All of 5 ft. 1 in. tall, Franklin is a divorced mother of three who dyes her hair platinum blond. Before she campaigned for mayor, Franklin had never run for an elected office. Outkast played at her inauguration.

When Franklin took office in 2002, Atlanta needed somebody a little out of the ordinary. Her predecessor, Bill Campbell, had completely blown the public's trust in city government. Two of his top aides pleaded guilty to charges of bribery, and Campbell is awaiting trial on a seven-count indictment for, among other things, bribery, tax fraud and corruption. Franklin inherited an $82 million budget deficit, which was about 20% of the entire city budget and $37 million more than she had been led to expect. Atlanta's homeless population was exploding, the city's infrastructure was fraying, the streets had not been maintained in eight years, and the sewers were leaking so badly that state and federal environmental agencies were fining Atlanta $20,000 a day.

How did Franklin respond? She started by committing what might have been political suicide. She cut 1,000 jobs from the city payroll and got the city council to approve a 1% sales-tax hike and a 50% bump to property taxes. To prove she could take it as well as dish it out, she laid off half her staff and cut her own salary by $40,000.

To restore faith in the local government, Franklin shepherded through the city council a new ethics code for municipal employees. She corralled 75 private firms to conduct studies of Atlanta's budgetary, infrastructure and homeless problems and perform a massive audit of the city government--pro bono. She organized a task force she called the Pothole Posse to go after the city's crumbling streets. She kept a running tally of cracks that were filled, combining good stewardship with quality political theater.

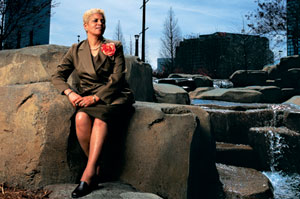

Shirley Franklin in Centennial Park. Photo from Time Magazine.

Shirley Franklin in Centennial Park. Photo from Time Magazine.Franklin, who was Atlanta's city manager from 1982 to '90 and served several key roles on its 1996 Olympics committee, is not just a rampaging reformer but also a skillful and diplomatic negotiator. Working with county and state officials, she managed to pull together a complex set of loans and agreements that will bring about $3 billion in upgrades and repairs to Atlanta's leaky sewers.

Since 2002, Franklin has turned in three balanced budgets, and in February she reported an $18 million revenue surplus. A $5 million homeless shelter is scheduled to open this summer. She plans to run for a second term this November, and so far nobody is even bothering to oppose her. For her achievements Franklin was awarded the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award this year by the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation. She is the first sitting mayor to be so honored. --By Lev Grossman. With reporting by Greg Fulton/Atlanta

3. Wonk 'n' Roller: MARTIN O'MALLEY / BALTIMORE

Twice since Martin O'Malley was elected mayor six years ago, Baltimore has been hit by blizzards. Each time, he had city workers phone as many as 25,000 elderly residents to ensure they were O.K. Then he had cops punch through the drifts, carrying bread, milk and toilet paper to those seniors running low. That's a snow job voters appreciate, and it helped re-elect O'Malley with 87% of the vote last year.

O'Malley, 42, has mastered that kind of retail politicking as a lifelong political buff. His parents met while working at the Democratic National Committee, and he was doing cheers for Hubert Humphrey by age 3. Gary Hart bought him his first legal beer at 21. O'Malley grew up in Washington's tony Maryland suburbs but fell hard for blue-collar Baltimore while attending the University of Maryland's law school there.

His urban innovations--primarily CitiStat, a computerized score sheet intended to make key city agencies like public works, housing, transportation and police more accountable--have brought other curious mayors on pilgrimages to Baltimore. "We've moved from a traditional, spoils-based system of patronage politics to a results-based system of performance politics," O'Malley says.

Cities traditionally measure the performance of municipal agencies at annual budget drills. But Citistat regularly confronts officials with citizens' complaints about broken streetlights or inadequate policing, allowing authorities to shift personnel and resources as needed. Every two weeks, managers head to see O'Malley or his top aides on the sixth floor of city hall to account for how well they have done just that. Workers who fare well can end up with Orioles tickets; managers who fall short have wound up with pink slips. The program has saved the city $100 million, O'Malley aides say. Last year Harvard University praised CitiStat for slashing overtime paid to city workers and cutting absenteeism in half at some agencies.

Thanks in part to O'Malley, Baltimore may be on the cusp of a renaissance. Its population slide--from nearly 1 million in 1950 to almost 650,000 today--has almost bottomed out. Commercial building permits jumped from $23 million in 2002 to $488 million last year. Such news heartens Baltimore residents, who sometimes jokingly call themselves Balti-morons for living in a city so grim it inspired NBC's Homicide: Life on the Street series. Drug use and crime in general are down, although O'Malley has only slightly dented the murder rate, which is five times New York's.

Martin O'Malley in his band at the Rams Head Tavern. The telegenic O'Malley is known for his brashness, a trait honed by years of fronting a Celtic rock band and being the eldest son among six siblings. He briefly gained national attention in February for saying that in cutting urban aid, President George W. Bush "is attacking America's cities" in much the same way that the 9/11 hijackers did. His fellow mayors grimaced, and O'Malley quickly backed off the analogy. He also attracted headlines when rumors he was having an extramarital affair ("despicable lies," O'Malley said) exploded into public view, and Republican Governor Robert Ehrlich fired an aide for spreading the story on the Internet.

Martin O'Malley in his band at the Rams Head Tavern. The telegenic O'Malley is known for his brashness, a trait honed by years of fronting a Celtic rock band and being the eldest son among six siblings. He briefly gained national attention in February for saying that in cutting urban aid, President George W. Bush "is attacking America's cities" in much the same way that the 9/11 hijackers did. His fellow mayors grimaced, and O'Malley quickly backed off the analogy. He also attracted headlines when rumors he was having an extramarital affair ("despicable lies," O'Malley said) exploded into public view, and Republican Governor Robert Ehrlich fired an aide for spreading the story on the Internet.Recently the mayor announced he was leaving his band, O'Malley's March, to concentrate on his day job. As he hung up his guitar at his last St. Patrick's Day show, he urged his fans to pick up green-and-white bumper stickers. They read O'MALLEY FOR GOVERNOR. --By Mark Thompson/ Washington

4. Able Amateur: JOHN HICKENLOOPER / DENVER

When John Hickenlooper ran for mayor of Denver in 2003, the betting in local political circles was that he should keep his day job, brewing beer. A Democratic civic activist, Hickenlooper was best known for owning the Wynkoop Brewing Co., the city's first brewpub, which he had opened in 1988 and built into a successful restaurant business. He had never run for office, not even for student council of his high school or college, Wesleyan, at which he earned degrees in English and geology. He also seemed a bit eccentric. As a bachelor, he offered a $5,000 bounty to anyone who could find him a bride and went on the Phil Donahue Show to discuss the contest (he eventually married in 2002). Geeky and lanky, he sported a boyish haircut and during primary debates cited intellectual tomes like The Rise of the Creative Class. For all his talk of balancing the budget and reforming the schools, he also harped on a prosaic matter: overpriced parking meters.

Photo from Time Magazine. That Hickenlooper, 53, cruised to victory may suggest that Denver citizens would vote for anyone who promised cheap parking (a pledge on which he delivered). But after 19 months in office his honeymoon still isn't over. Not only do 75% of voters in metro Denver approve of his job performance, but 61% of folks in the region, including the Republican-leaning outlying suburbs, rate the mayor favorably as well, according to a new poll. Asked to explain his popularity, Hickenlooper fumbles for an answer. "I try not to gloss over reality," he says. "If I don't know the answer, I'll say that."

Photo from Time Magazine. That Hickenlooper, 53, cruised to victory may suggest that Denver citizens would vote for anyone who promised cheap parking (a pledge on which he delivered). But after 19 months in office his honeymoon still isn't over. Not only do 75% of voters in metro Denver approve of his job performance, but 61% of folks in the region, including the Republican-leaning outlying suburbs, rate the mayor favorably as well, according to a new poll. Asked to explain his popularity, Hickenlooper fumbles for an answer. "I try not to gloss over reality," he says. "If I don't know the answer, I'll say that."What he's reluctant to say is that he dispensed with the partisan and sometimes imperious manner of past Denver mayors to accomplish quite a bit during his brief tenure. When Hickenlooper, who is called Mayor Hick, took office in July 2003, he inherited a $70 million budget deficit, the worst in city history. He eliminated the shortfall without major service cuts or layoffs, convincing city employees that they should accept less pay and instituting mandatory leave days (he slashed his salary 25%). Bucking the wisdom that you don't take on city-hall unions, he pushed for an incentive-based compensation system for public employees, which voters approved in 2003. And in his biggest score, he won approval for a $4.7 billion mass-transit plan, which involved persuading voters, along with about a dozen mayors in seven regional counties, to back a sales-tax hike.

Hickenlooper's honeymoon has not been without flare-ups. Before he took office, Denver's police department had been facing public criticism over allegations that officers were using excessive force. Hickenlooper appointed a task force to look into the matter and recently nominated a civilian monitor to oversee and critique internal police investigations. Civil-liberties groups complain that the civilian monitor lacks enforcement authority.

But with the Denver economy recovering, the police controversy doesn't seem to have dampened enthusiasm for the mayor, a colorful guy who rides around on an Aprilia scooter and once suggested that employers earmark a percentage of their payroll to buy local artwork. "If I make a mistake, I'll apologize," says Hickenlooper. So far, no apologies seem necessary. --By Daren Fonda. With reporting by Rita Healy/Denver

[Also, check out this recent article about Denver's revitalization from the Christian Science Monitor.]

5. Reluctant Pol: MICHAEL BLOOMBERG / NEW YORK

From the moment you enter his office at New York's city hall, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, 63, wants visitors to know that he is not your average politician--or a politician at all. Bloomberg, you see, doesn't really have an office. Instead, he sits alongside much of his staff in the middle of what is known as the bullpen, a large, former public meeting room now packed with corporate cubicles like a Wall Street trading floor. "Walls are barriers, and my job is to remove them," says the billionaire businessman who made his fortune by building his namesake financial-data-and-media empire. "I wasn't hired to do well in the polls. I was hired to do a good job."

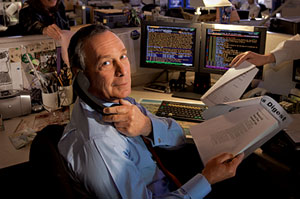

Bloomberg at the office. Photo by Time Magazine. By a variety of measures, from the falling crime rate to the improving economy, Bloomberg has done just that. And he has done it in a post often described as the second toughest job in America--a job he inherited from the most famous mayor in the world, Rudy Giuliani, in the wake of 9/11 and a bearish stock market, no less. Bloomberg has brought an unprecedented level of efficiency and transparency to New York City government. "The best thing is, he doesn't seem to be making decisions based on a four-year calendar," says Jonathan Bowles, research director at the Center for an Urban Future.

Bloomberg at the office. Photo by Time Magazine. By a variety of measures, from the falling crime rate to the improving economy, Bloomberg has done just that. And he has done it in a post often described as the second toughest job in America--a job he inherited from the most famous mayor in the world, Rudy Giuliani, in the wake of 9/11 and a bearish stock market, no less. Bloomberg has brought an unprecedented level of efficiency and transparency to New York City government. "The best thing is, he doesn't seem to be making decisions based on a four-year calendar," says Jonathan Bowles, research director at the Center for an Urban Future.Over the past three-plus years, Bloomberg has trimmed a $6 billion budget deficit (in part by raising property taxes); spurred a wave of new economic development, especially in the four other boroughs besides Manhattan, so often ignored by his predecessors; taken control of the city's ailing schools and instituted a uniform math and reading curriculum, although the jury is still out on how much that will actually enhance students' educations; and improved the city's quality of life by banning smoking from all restaurants and bars, cracking down on noise and creating a one-stop complaint-and-question line, 311.

Perhaps most impressively, Bloomberg has managed to do that while being "the first mayor in a long time who has not been a polarizing figure," as Mitchell Moss, professor of urban planning at New York University, puts it. That is not to say his constituents necessarily appreciate the Republican mayor. In a city where Democrats outnumber Republicans 5 to 1, recent polls show that only about 40% of registered voters approve of his job performance. The majority of New Yorkers have also told pollsters they don't want to build a football stadium for the New York Jets on Manhattan's West Side, but Bloomberg is pushing hard for one anyway. In his mind, the stadium, which will double as a massive convention center and could also be the center of the 2012 Summer Olympics, for which New York is making a bid, is the kind of long-term economic bet that great cities, like great companies, have to make. "It is investing for the future," Bloomberg declares, sounding suspiciously like a politician, before adding a key, most impolitic warning, "with no guaranteed return." --By Daniel Eisenberg

Honorable Mention: GAVIN NEWSOM / San Francisco

For facilitating the marriage of nearly 4,000 gay couples in his city last year, Gavin Newsom is famous countrywide--and controversial. But at home in San Francisco, the mayor is simply adored. It's the main reason Newsom, 37, who barely squeaked into office in 2003, now enjoys an eye-popping 80% approval rating in America's ultraliberal gay mecca. But it is by no means the only factor. The workaholic millionaire restaurateur has packed more productivity into his first 15 months than many mayors manage in two terms. By diverting welfare payments for the homeless into a housing fund, Newsom's administration has reduced the number of long-term homeless in the city 41% and cut deaths on the street 40%. Health insurance is now guaranteed to every uninsured San Francisco resident under the age of 25 at a cost of $48 a year. Newsom also personally halted a strike at 14 hotels across the city late last year. He stood on the picket lines with unions, though the hotel lobby had written checks to his campaign, before brokering a cooling-off period that still continues. "I'm the first to say that I've no idea what I'm doing," says Newsom. "There's no manual here for how to be mayor." Tip for publishers: sign him up to write one. --By Chris Taylor/San Francisco

1 Comments:

But if these options aren’t an option for you, then you may be payday loans online same day considering a payday or quick cash loan.

Post a Comment

<< Home