Urban Health, Nasty Cities, Broken Windows, and Community Efficacy

Old and new in Manhattan. Photo by FunkandAmis.

In the December 5th, 2004 Los Angeles Times, Dr. Neal Kaufman wrote an op-ed piece, "Good Design Keeps the Doctor Away" which makes good points that quality built environments that are pedestrian-centric are healthier places to live. I do take "offense" to the article in some respects because it attributes the problems to cities per se rather than to poor planning and development decisions. (Dr. Kaufman just sent this article to the public.spaces list.)

Rather than attack the problems (as Jane Jacobs says in Death and Life in Great American Cities, "if you want to get rid of rats, focus on getting rid of rats. Tearing down neighborhoods and rebuilding isn't going to get rid of rats--badly paraphrased) I feel that Dr. Kaufman unduly denigrates cities: "Are our cities making us sick?" and stating that: "Today's cities are plagued with traffic, violence and overcrowding."

Here's my spirited response:

Violence. One, all parts of all cities are not equal. Violence is associated with concentrated poverty. Concentrated poverty may be associated with cities, but it's not a requirement. Because of regional disparities, center cities tend to be the catchment areas for those with the greatest needs, and in many respects I think of this as a "quality of life" subsidy that center cities provide to neighboring suburbs. In short,

this has to do with SES.

This is politically incorrect to say, but fewer than 10 caucausians are murdered in DC in an average year. (cf. The Future Once Happened Here). There are plenty of people in the city that buy food at farmers markets, walk and bike, exercise, eat relatively healthily, and don't smoke and drink limited amounts of alcohol. Again, health behaviors are linked to levels of educational attainment and SES.

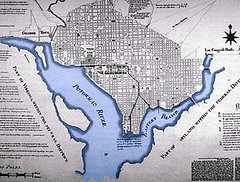

Overcrowding. Just five square miles of DC was designed to accomodate 1 million residents (L'Enfant Plan), yet we have but 580,000 people in 39 square miles of non-federal lands (DC's peak population was 802,000).

The L'Enfant Plan for the "Old City" of Washington, DC. From the NCPC website.

I would gladly live in Manhattan or Brooklyn, if only for Mercury Lounge, Bowery Ballroom, Central and Prospect Parks, and Union Square (I probably prefer the Library of Congress over the NY Public Library). Density isn't bad. High-density has its advantages too. Concentrated poverty doesn't necessarily mean overcrowding. To address the problems of concentrated poverty, the nation would have to be willing to invest in people (schools, libraries, workforce development) and for various reasons, such investments often haven't been too well targeted. These days, the war on poverty has degraded into a war on cities.

Detroit has 50+ empty square miles. Cleveland has less than 500,000 residents, when it once was the fourth most populated city in the U.S. Our big cities have plenty of capacity for more residents. Overcrowding? Where?

Traffic. Except for the fact that new residents are imprinted with a car-centric lifestyle and planning and development paradigm, except for a few periods of the day, traffic isn't an issue in DC--because we have transit, walkers, and bike riders, in addition to drivers. (See my blog entry from last week on a radio interview with Dan Tangherlini, DC's director of the Dept. of Transportation.)

Frankly, suburban traffic is much much worse, because they don't have a street grid to provide multiple travel paths (there is a diagram of this point in Death and Life of Great American Cities), and usually walking, biking, and transit are not time-efficient alternatives.

I do think that design matters. But there is no need to make the city a bogeyman to make your point.

Yes, more people are murdered in cities. But as many or more people die in traffic accidents in the suburbs. (See this blog entry for an extended discussion of this with regard to teens.)

The number of people that die in traffic deaths in the U.S. is more than double than that of people murdered. I am not promoting murder as a preferred way to die, but I would bet that most traffic deaths are not occuring in the center cities (for one thing, you can't drive very fast).

Related to Dr. Kaufman's piece, FrozenTropics alerts us to a brief from the Rand Corporation "Does Neighborhood Deterioration Lead to Poor Health" which looks at this same issue. The "collective efficacy" philosophy (Felton Earls) takes issue with the "broken windows" theory (George Kelling, James Q. Wilson) yet one of the key findings of the Rand paper is that "the association between collective efficacy and lower rates of premature death was not seen in neighborhoods with a high percentage of boarded-up stores and homes, litter, and graffiti."

To me, this seems like a resounding endorsement of the broken windows theory, which is something I've discussed for awhile.

This was something that was written on the public.spaces email list in January 2004. I responded to this excerpt from New York Times article about Earls' work in a couple posts, one of which I've included below. From the article: "As for policy implications, Dr. Earls said that rather than focusing on arresting squeegee men and graffiti scrawlers, local governments should support the development of cooperative efforts in low-income neighborhoods by encouraging neighbors to meet and work together. Indeed, cities that sow community gardens, he said, may reap a harvest of not only kale and tomatoes, but safer neighborhoods and healthier children."

Here was my response then:

Actually, I understand the point that Dr. Earls makes about the necessity of neighborhood residents in organizing, building community capacity, using the asset-based approach, etc. It's absolutely necessary. But it takes a lot of time. And unfortunately, "organizing" capacity isn't always present in such neighborhoods, even if there are plenty of people capable of contributing. PLUS, if you read about "fixing broken windows" or whatt hey call "problem-oriented policing" THE REALITY IS THAT IT IS ALL ABOUT BUILDING COMMUNITY CAPACITY.

The reason that I cited the Siegel and the Dalrymple books is because they talk about the issue of responsibility. Many people in my community expect others to fix things for them. That includes the big things as well as simple things, such as picking up litter. The Goetze book has really shaped my thinking by focusing on how get a community to self-invest rather than flee. Self-investment means picking up trash, or talking to people hanging on the street corner, as well as things like painting your house, planting in your front yard,etc. What do you do when many people in the neighborhood support thef orces that create disorder? That is the part that I didn't see in the NYT article.

I don't know if Earls takes the phrase "fixing broken windows" absolutely literally. If he does that's a mistake. Here's an example that I have been dealing with, a situation a block from where I live and it shapes my thinking on these issues.

The two-block stretch is about the worst in the western part of the neighborhood, at least one person/year is murdered at that intersection. (nb. what's "bad" in my neighborhood is less bad compared to some other parts of DC, and at the same time, it's much worse than other areas and we are 10 blocks or so from the U.S. Capitol, and now our houses sell for in excess of $250,000).

One of the big problems is that a church at the same intersection owns many properties there--including three of the four key corner properties. We lost a close fight in terms of a historic propertynomination--they want to tear down 2 frame rowhouses built in 1875 for aparking lot (such a use isn't allowed)--but they have let the properties languish for over a decade with nary a fine. My personal belief is that they don't manage their properties responsibly in order to keep the area in disarray, which allows them to purchase other properties more cheaply (less demand=lower price). In any case, the Church is "shocked, shocked" when we point out to them how they take care of their property contributes to the serious problems that they claim to be concerned about. They are shocked that we think that occupied houses are better mid-block than parking lots, that "these old wood houses" have value, etc.

The buildings, two of the oldest buildings north of H Street NE in Washington DC were in bad shape, but it was through neglect and disinvestment. Note: as neighborhood people know, the buildings came down and the church is parking on the lots, illegally. Photo by Peter Sefton.

If these properties had been occupied and maintained all along, they wouldn't have become cesspools for disorder and drug dealing. If more people lived in that immediate area, nearby properties wouldn't have slid into vacancy and neglect, etc. (We are still negotiating with them to preserve and rehabilitate the properties rather than demolish them for a parking lot that will never be built--we lost...)

Again, I would reiterate that building community capacity (social environment) and the physical environment must be addressed simultaneously. Perhaps one of the difficulties in studying the impact of the broken windows theory has something to do with a point made by Frederick Herzberg in his "motivation-hygeine theory" of organization behavior and development -- he says that you need to have structure (hygeine theory) to function. If you have it you don't necessarily function "better" but if you don't have it, there is "dissatisfaction" and there is great dysfunction.

In my work in neighborhood commercial district revitalization, one of the things my committee is responsible for is "image development." Unfortunately, we have a schism within the organization--one group believes that the commercial district is great as is and fully ready to be able to be marketed to the entire Washington region--the other group believes that we have a long way to go in order to be able to reach beyond the current customer base let alone much of the immediate neighborhood (which doesn't shop on H Street).

E.g., I find it incredibly frustrating that the merchants by and large don't pick up trash in front of their stores. Now sure, they didn't throw it there, but how the street looks defines their business and their ability to compete, market, and make customers feel comfortable shopping there. And we have graffiti, loitering, too many establishments that sell alcoholic beverages (I have probably written about my efforts on this previously), crime, boarded up buildings, etc. Anyway, I have focused our image development efforts (in face of great criticism) on our internal markets--merchants, residents, current customers--because I fervently believe that until we (residents, merchants, customers) start taking better care of our commercial district by keeping it clean, having great stores, etc., we can't expect others to patronize it.

I could write about these issues all day. And I wouldn't mind a grant or two from the National Institute of Justice.

Labels: broken windows theory, community efficacy theory, quality of life advocacy

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home