The schism in architecture over places vs. "art-itechture"

New York Times image.

New York Times image.Yesterday's LA Times has a commentary about the arguments within the architecture profession over "New Urbanism" and its "domination" of the rebuilding agenda in Mississippi and possibly in Louisiana. See "In the rush to rebuild, a house divided: While the Gulf Coast lies in ruins, two camps of architects are dueling over the direction of post-Katrina reconstruction."

I don't think the piece makes the arguments very clear, because too often people get hung up on the traditional aspects of the designs that tend to be employed in New Urbanist projects, and that gets in the way of the substantive issues.

1. New Urbanism is about urban design as opposed to suburban design. Probably the best way to think of it is in terms of Jane Jacobs' points in Death and Life of the Great American City, in particular her points about the necessity of mixed-uses, small blocks, connected within a grid system, and a focus on life at the street and sidewalk level. A way to think of it is as a focus on people as pedestrians, to plan around people rather than cars.

2. Modernism isn't about context or connection at all, or permanence, it's about buildings as art, as objects. Frank Gehry in Bilbao is a perfect example.

3. However, when it comes to actual developments in the suburbs, the challenge that New Urbanism poses isn't that substantive way, but it is about whether or not buildings and places are connected or not, and whether they promote sprawl and deconcentration.

4. Because of the planning, development, and financing paradigms of the housing market, New Urbanism projects are mostly about "New Suburbanism" or creating connected greenfield subdivisions vs. unconnected subdivisions. I call this "Smarter Sprawl," and prefer to focus my energies on "repopulating and revitalizing center cities." To my way of thinking, the average greenfield New Urbanist development isn't much different from regular old sprawl.

Washington Post Photo by Bill O'Leary. Liz Waetzig, working mother of 3, is the envy of our reporter for her fabulous lifestyle in Kentlands, Md. Pictured, the family sets out on foot towards the nearby shopping center for a Saturday lunch together. L-R: Grace Williams-9, Liz Waetzig, Erin Williams-7, Chad Waetzig, and Julia Waetzig, 8 months, in stroller.

Washington Post Photo by Bill O'Leary. Liz Waetzig, working mother of 3, is the envy of our reporter for her fabulous lifestyle in Kentlands, Md. Pictured, the family sets out on foot towards the nearby shopping center for a Saturday lunch together. L-R: Grace Williams-9, Liz Waetzig, Erin Williams-7, Chad Waetzig, and Julia Waetzig, 8 months, in stroller.There are really two arguments then. How to build or revitalize communities is one, and the second is whether or not New Urbanism makes a difference in particular regions. But the arguments get mixed up and hung up over the design, and headway isn't made.

If people like Mike Davis are against urban design and connectedness, then their arguments are worthless, because that's the primary aspect of "New Urbanism" that matters--it's not about "faux" traditional designs that are "inauthentic."

From the article:

The New Urbanists, meanwhile, have been more skilled at making themselves welcome on Main Street and in the corridors of power — even as their stock among fellow architects, particularly young and urban ones, has plummeted. No architectural interest group attracts as much criticism as the CNU. But the group's leaders are increasingly able to brush off those gripes, because they have made the calculated decision that the people whose minds are worth changing include everyone but architectural elites.

"New Urbanism is a multidisciplinary effort that has to do with planning, with resource management, with land-use issues," Calthorpe says. "So whether we wind up with architecture critics on our side, I really couldn't care less." ...

Whatever you make of the CNU agenda or of the developments that have been produced under its banner, you can't help but be impressed by the organizational strength it has displayed in rushing into the planning breach along the Gulf Coast. More than anything, the effort brings to mind the way Republican operatives bested Democratic ones in certain crucial swing states during the 2004 presidential election. The Biloxi charrette, in other words, may go down as the architectural elite's Ohio: the place it watched rather helplessly as its ideological opponents outclassed it not through nimble thinking or grand theory or inspiring plans but simply by being more disciplined and better organized. And there is no need, in this version, for a recount.

________

I don't even think it's this complicated. You can think of the "anti-NU" position as one of chaos, without an overarching philosophy, framework, and approach. Without such, how can you organize, how can you respond, and how can you even approach the problems that are before you?

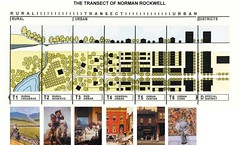

The transect of Norman Rockwell.

The transect of Norman Rockwell. Architect and author John Massengale has written a nice blog entry about the transect and what it means. From his entry:

The New Urban Transect describes the range of natural and built environments from the heart of the wilderness to the center of the city. The diagrams for the Transect (here and here) show these as Transect Zones: each urban T-zone is a neighborhood with most or many of the needs and activities of daily life within a short five-to-ten minute walk. The Transect reflects the New Urban reaction to the sub-urban way we've been building for the last 50 years, a way of building that not only requires that everyone drive everywhere for virtually everything, but that usually creates non-places where no one wants to walk even if they can. In this sub-urban world, only nature (T-1 and T-2) is worthy of our attention — everywhere else we retreat to our houses, cars and backyards.

T-zones have implications for architectural and urban form not so different from the old New York maxim for clothes, “Don’t wear brown in town.” A tower appropriate for Wall Street in Manhattan doesn't fit on the green in Woodstock, Vermont. A wood frame Greek Revival house with a lawn behind a white picket fence doesn’t work on the plaza at Rockefeller Center. The fence is different on Wall Street than in Woodstock: so are the sidewalk, the streetlamp on the sidewalk and the size of the setback from the street. And none of them are appropriate in the middle of the Yellowstone Valley or the wilds of Alaska.

This may all seem obvious, but it is not the way architects, planners, builders and developers have worked for the last half-century. So the Transect and the T-zones are the basis for Smart Codes, which are tools for making better places. Smart Codes reject the fetishized objects of Starchitecture as the goal of building, and replace the system of Zoning that produced American sprawl by zoning virtually everywhere — from city to country — for the same low-density, single-use, auto-dependent zones. The system in which McDonald’s and CVS thought one building type, with the parking out front and the drive-thru on the side, fit all.

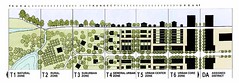

The traditional transect diagram.

The traditional transect diagram.Check out these resources from DPZ on the transect.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home