Some more thoughts about trying to institute problem-oriented policing in DC

There are many "just this one things" that we need to do to rebuild center cities. One obviously is the quality of public schools, but primary is public safety. A lot of this is about perceptions, but a lot has to do with the fact that there tends to be more crimes in center cities for many reasons, including a greater number of people suffering persistent poverty, and a goodly number of potential victims.

Because of the success of William Bratton in NYC and the implementation of what is called "Broken Windows" style (or problem-oriented) policing, everyone clamors for similar styled policing in their own communities.

But then it gets tied up in politics, perceptions of racism, and other issues. E.g., someone on the Brookland e-list commented that as incomes in a neighborhood rise, crime falls. That set off a hullaballoo. There was a parallel thread on the poor maintenance of the park at Turkey Thicket, and then someone wrote about "Broken Windows" theory, linking it to both threads.

This is what I wrote:

I am a big proponent of "Broken Windows" theory and advocate for it strongly here. There are some complicating factors though.

(1) I think part of the recent perceived or actual increase in crime is a function of increased disparities. I have noticed similar upticks in the past. (And I think the increased use of weapons is a function of needing to ensure success as well as an increased likelihood of resistance and/or assistance from others.)

(2) Although at times the perception of crime rates is a function of "new" people with different histories. This isn't a negative, just a comment. E.g. recently I was talking with a neighbor about crime in the neighborhood and I said that I can't help but compare today to the time (in the late 1980s) when 30 people or so were murdered in an 18 month period (during the crack epidemic and the height of Rayful Edmond's operation), hearing gunshots every night, helicopters overhead, etc., so obviously I'm going to think today is better regardless.

(3) Chief Ramsey is a lot better than I thought (except on civil liberties issues). A big part of the problem with instituting problem-oriented policing is the need for change in two areas:

(a.) the police department itself (which like all DC government agencies has its share of personnel commitment issues--there's a fair amount of deadweight, for the police department this came with the hiring of 1,000 police officers during a piont of time in the Barry Administration, and perfunctory background checks were conducted--many "problem" police officers were hired during this period) and

(b.) the Court system and its willingness to "define deviance upward" (a reversal of the Moynihan thesis) in order to be as concerned about "petty" crimes such as breaking glass in playgrounds (which is a way to reduce preferred uses in a playground--no kids means no kids and parents which means the creation of an order vacuum more conducive to the support of disorder.

Anti-war protest in DC. Photo from Washington Insider Tours.

Anti-war protest in DC. Photo from Washington Insider Tours.In the last couple years, I have seen some major impacts in terms of quality of investigation, arrests, etc., which I think is the result of having the time to deal with the personnel issue. Obviously, the quality of the operators at the Emergency Call Center continues to be a big issue. And there are others.

But judges vary significantly in terms of how they rule and sentence, and I can't imagine people being "convicted" of quality of life crimes like littering. Even BORF or NORES and KOMA received, in my opinion, very little time for significantly deleterious acts.

Part of my sentencing desire for NORES and KOMA was that they would have had to clean up the graffiti and for this to be televised on Channel 16. And BORF needs to be jailed at night after he finishes school, for awhile, in my opinion. One month isn't enough. (I know this doesn't sound very progressive, but I am not big on disorder promotion.)

Koma-Nores graffiti on H Street NE, Washington, DC. PHoto by Inked78.

Koma-Nores graffiti on H Street NE, Washington, DC. PHoto by Inked78. Borf, artist or vandal? Flickr photo by Indy Charlie.

Borf, artist or vandal? Flickr photo by Indy Charlie.(4) But the real problem with instituting real Bratton style policing* in DC comes back to something that touched off this thread (which I have studiously avoided commenting on). Enforcement would fall disproportionately on people who commit crimes, including quality of life offenses. People who do such tend to be lower-income. In this city, they would tend to be African-American primarily, but also Hispanic. (*Which is different from the post-Bratton Giuliani period associated with police abuse.)

In a majority minority city like DC, I think the political fallout of highly increased enforcement "against" African-Americans in particular would be significant, and no politician in the city would be willing to take such heat.

I think that's the reason true "problem-oriented" policing of the Bratton style has not been fully endorsed or implemented in DC.

Officers from the 6th District's auto theft unit arrest a young man for allegedly driving a stolen car with stolen plates. (By Jahi Chikwendiu -- The Washington Post)

Officers from the 6th District's auto theft unit arrest a young man for allegedly driving a stolen car with stolen plates. (By Jahi Chikwendiu -- The Washington Post)However, yesterday's Post had a nice article, about "problem-oriented policing" in DC's 6th District, focused on the epidemic of stolen cars by youths. (Over the past few years this has resulted in a number of deaths of bystanders killed by speeding joyriders.)

The article "Hot on the Trail of Young Joy Riders: Informants, Patience Help D.C. Squad Catch Up With Slippery Thieves," discusses how focused policing, recognizing that a few youths are responsible for a great number of stolen cars, and tenacity has "put a substantial dent in the city's auto theft problem.... Last year, although auto thefts dropped 30 percent there, the district led the city in stolen cars. But this year, it no longer does."

More than 10 years ago, I remember reading an article in Chicago magazine about the police precinct with the most reported crimes in the city. More than 1/2 the number of crimes were committed by a relatively small number of people.

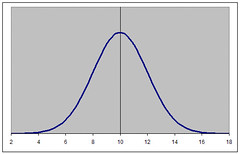

A graph of the "Law of Power Distribution."

A graph of the "Law of Power Distribution."

Malcolm Gladwell writes about this aspect of public policy, in the recent New Yorker article, "MILLION-DOLLAR MURRAY." The article is summarized as "Why problems like homelessness may be easier to solve than to manage," because it focuses on the often ignored fact that public policy problems aren't one of the normal distribution curve, but that if it were to be graphed "[i]t would look more like a hockey stick. It would follow what statisticians call a “power law” distribution—where all the activity is not in the middle but at one extreme."

For example, Gladwell describes a more detailed analysis of homelessness:

Culhane then put together a database—the first of its kind—to track who was coming in and out of the shelter system. What he discovered profoundly changed the way homelessness is understood. Homelessness doesn’t have a normal distribution, it turned out. It has a power-law distribution. “We found that eighty per cent of the homeless were in and out really quickly,” he said. “In Philadelphia, the most common length of time that someone is homeless is one day. And the second most common length is two days. And they never come back. Anyone who ever has to stay in a shelter involuntarily knows that all you think about is how to make sure you never come back.”

The next ten per cent were what Culhane calls episodic users. They would come for three weeks at a time, and return periodically, particularly in the winter. They were quite young, and they were often heavy drug users. It was the last ten per cent—the group at the farthest edge of the curve—that interested Culhane the most. They were the chronically homeless, who lived in the shelters, sometimes for years at a time. They were older. Many were mentally ill or physically disabled, and when we think about homelessness as a social problem—the people sleeping on the sidewalk, aggressively panhandling, lying drunk in doorways, huddled on subway grates and under bridges—it’s this group that we have in mind. In the early nineteen-nineties, Culhane’s database suggested that New York City had a quarter of a million people who were homeless at some point in the previous half decade —which was a surprisingly high number. But only about twenty-five hundred were chronically homeless.

Normal statistical distribution or "Bell Curve."

Normal statistical distribution or "Bell Curve."

Just like it makes little sense to search a 75 year old grandmother at the airport as if she were a likely terrorist, it makes sense to look at social problems in a systematic, data-rich, analytical fashion in order to address and deal with structural conditions.

For public safety and quality of life issues, that's what Broken Windows theory is all about. And it appears that DC's police department is implementing this approach more and more.

Throwing money at problems tends to accomplish very little, because money isn't the issue as much as it is focusing on the right problem, rather than attempting to ameliorate symptoms to little effect. (cf. initiatives to fund school repair and modernization and/or to create a new Central Library. Are the problems the buildings or the people and systems responsible for managing and maintaining these facilities, not to mention the quality of the processes and functions that are supposed to occur within these agencies-systems?)

Now on to other agencies...

MPD Police Chief Charles Ramsey Photo from Washington Insider Tours.

MPD Police Chief Charles Ramsey Photo from Washington Insider Tours.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home