The real answer is throughput, but not if you're asking the wrong question

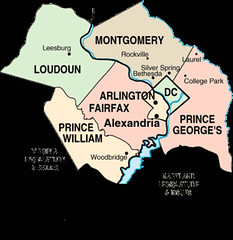

The Washington, DC Metropolitan Area, image from the Coalition for Smart Growth.

The Washington, DC Metropolitan Area, image from the Coalition for Smart Growth.Speaking of our friends in Prince William County, there is an article in today's Post about how the County wants to create a state-chartered "Department of Transportation" to oversee road building as the county's population growth is outpacing the expansion of infrastructure. (See "With DOT, County Acts to Fill Void: Va. Can't Meet All Pr. William's Road Needs, Officials Concede.")

Hmm. I don't have the energy to make some smart-ass comment about this vis-a-vis the WMATA sales tax debacle in the Virginia Legislature that is being abetted by, among others, Prince William Representatives Jeffrey Frederick and L. Scott Lingamfelter.

Although I think that the other Northern Virginia Legislators should vote down any attempt to pass the enabling legislation for PWC's DOT. After all, if PWC wants to go its own way, it should go its own way on its own resources, at least in terms of its eager willingness to be somewhat of a free rider on WMATA.

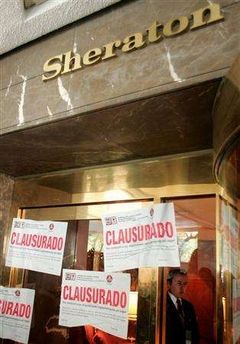

A hotel worker stands guard at a door where 'Closed' notices have been posted in the Hotel Sheraton Maria Isabel in Mexico City, February 28, 2006. REUTERS/ Henry Romero. The city did this "building code enforcement action," since rescinded, in response to a refusal (pushed by the U.S. government) by the hotel to provide lodging to a delegation from Cuba. Such building code enforcement activities can be used by governments (and the Growth Machine) to help push forward development schemes. Why not use similar enforcement actions to punish Prince William County's bus services to Washington DC in response to county legislators deliberate inaction on funding for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.

A hotel worker stands guard at a door where 'Closed' notices have been posted in the Hotel Sheraton Maria Isabel in Mexico City, February 28, 2006. REUTERS/ Henry Romero. The city did this "building code enforcement action," since rescinded, in response to a refusal (pushed by the U.S. government) by the hotel to provide lodging to a delegation from Cuba. Such building code enforcement activities can be used by governments (and the Growth Machine) to help push forward development schemes. Why not use similar enforcement actions to punish Prince William County's bus services to Washington DC in response to county legislators deliberate inaction on funding for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.Anyway, the county probably should call the agency a department of road building, because road building ≠ transportation.

The real focus should be on results, on vehicle and passenger throughput. As I've written before (based on a presentation by Jeff Tunlin from Nelson Nygaard), here are some throughput numbers that are relevant:

Throughput of one lane of road for one hour

Automobiles = 900 cars moving approx. 900 - 1800 passengers/hour

Traditional bus service = 6,250 passengers/hour

Bus Rapid Transit = 10,000 passengers/hour

Light Rail = 16,000 passengers/hour (in a compact development scenario, this number can be 2 to 4 times higher)

As long as the dominant development paradigm is deconcentration (what people call sprawl) it is impossible to substantively improve throughput if the preordained answer revolves around the automobile as the primary "mobility" mode.

I've mentioned from time to time Steve Belmont's Cities in Full. Here's an interesting paragraph from the first chapter:

A net housing density of at least 15 dwelling units per acre--nearly double the density of most detached-house neighborhoods--is required to sustain a high level of bus service (120 buses per day on routes spaced no more than one-half mile apart). And densities much higher than that are necessary to overcome automobile dependence. In the American city, fewer than half of all vehicle trips originating in a neighborhood will be made on transit unless the neighborhood's net housing density exceeds 60 dwelling units per acre. (p. 9).

This leads us to today's Steve Eldridge's "Sprawl and Crawl" column in the Examiner. He's not actually asking the wrong question in the column "An unclear vision?," but the column focuses on the choke points of the "hub and spoke" system that defines the subway transit model, rather than what creates the choke points--deconcentration and decentralization of development in the metropolitan area--which makes transportation efficiency virtually impossible in the Washington DC region.

First, a grid system such as in DC actually moves traffic more quickly.

Second, a hub and spoke system works fine if and only if land use planning "forces" new residential and commercial development to be planned and developed with mobility in mind. This is also known as compact development.

I don't find commonly used terms like "smart growth" or "transit-oriented development" to be accurate or useful enough to focus on the real problems of deconcentration and decentralization. As terms, SG and TOD are more about keeping the "Growth Machine" happy, mostly the equivalent of slapping paint on a building without priming first, without making any needed fixes to other systems like the flashing and gutters.

I hate the term smart growth, preferring something like "sustainable land use and resource planning." The real "answer" is efficient development, when efficiency is defined as using inputs (land, energy, government resources, etc.) in cost-effective ways that also promote and extend livability rather than to diminish it (i.e., you can reduce the use of government resources by not building parks or libraries, but that hardly makes life better for people).

Efficent development can't be obtained in a system that continues to deconcentrate and decentralize because you're not able to achieve either the density of housing necessary to support transit or a focused number of destinations (work, shop, play, learn) that can be reached relatively efficiently by transit.

Belmont discusses "monocentricity vs. polycentricity vs. non-centricity" in the chapter "Recentralization of Commerce." He pulls together a variety of arguments that make clear that the kind of "let it all develop on the edge because it's efficient" writings of the pro-suburbanist Joel Garreau (Edge City: Life on the New Frontier, which features Tysons Corner as the idyll) are quite flawed.

As was proven as long ago as 1986 (20 years ago...) urban ecologist Valerie Haines found that "decreasing spatial separation and the clustering of land uses reduces trip length for nonwork and work trips without producing congestion." (Note to Steve Eldridge, a street grid has a similar effect, by providing multiple routes with fewer choke points.) UCB professor Robert Cervero has researched this question exhaustively, with the same conclusion.

Belmont points out that "decentralized transit [which is the type of system developed into the WMATA subway system] fails to reduce suburban automobile dependence because (1) few suburban stations high-density commercial development; (2) suburban station-area residents use their cars for non-work trips; and (3) suburban-area workers commute in their cars. (p. 270-1)

By extension this helps confirm a couple of the points made by Sam Smith and reprinted in an earlier blog entry:

The subway has removed jobs, businesses, and tourist facilities from the city and has made it possible for ever larger number of suburbanites to exploit DC tax free (thanks to the ban on a commuter tax). DC now has the greatest percentage increase in daytime population owing to commuters of any city in the country but it fails to benefit from this increase commensurate to the costs involved.

- The subway did not compete with the automobile as promised. In fact, it increased street traffic by attracting new development to which only a portion of the workers came by subway. The rest added to the street traffic.

Decentralization forces households to make more and longer routine trips, mostly by car. Given the very real capacity issues -- one lane of road in one hour can move only 900 automobiles -- there is no solution when the answer is defined around the automobile.

Without urban growth boundaries concerned with maximizing efficient mobility, not just preserving open space, I can't see how this system will change.

People like me will continue to make mobility choices based on efficiency and connection, and people like L. Scott Lingamfelter will continue to advocate for building roads.

Steve Eldridge's column is definitely right in his summation:

We are in trouble here in terms of our transportation systems, and the only way out of this is if some of the basic legislative systems get changed. Then we can start talking about the hubs and the spokes.

And of course, this is a problem virtually everywhere across the country, all major metropolitan areas are multi-jurisdictional, even if these jurisdictions aren't necessarily across state lines, the variety of different jurisdictions possessing multiple and conflicting objectives makes efficient, compact, mobility-focused development virtually unobtainable.

Index Keywords: transit; mobility

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home