Bringing buildings back is really about bringing urban neighborhoods back

Entry: Tuesday September 19, 2006

Yesterday, I wasn't going to go to the Smart Growth talk at the National Building Museum by Alan Mallach, about his new book, Bringing Buildings Back, because I have too much to do.

I'm glad I went.

Frankly, it's not like it was anything new. I've figured out most of what he said, based on 7 years or so of pretty serious involvement and analysis of urban revitalization, mostly in DC. But it would have been a lot easier and quicker to have had this book (just like I wish I had been able to read Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City before moving into the city).

But since you don't hear this from just about anybody else, it was great to have him confirm it (it also parallels the work done by organizations like NeighborWorks and the Casey Foundation in working to indentify the factors that influence comprehensive, successful neighborhood stabilization and improvement).

So I bought the book, which I don't often do.

His thesis, based on a lot of field experience and research, is that vacant buildings--I was impressed that he never used the words "blight" or "dilapidated" but called the buildings "abandoned" or "nuisances"-- are a tremendous underutilized asset providing cities with great opportunities.

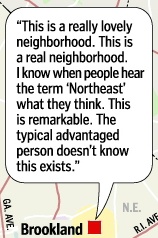

We talked for quite a bit after he was finished with his book signing, and he used the phrase minimally acceptable market threshold, referring to how you augur urban revitalization, neighborhood by neighborhood, in ways that attract the people who have choices, the ability to live wherever they want. This dovetails with the quote from Richard Florida in yesterday's Post article, "The City as Modern Muse," about Brookland:

Extracted from a Washington Post graphic produced by Nathaniel Vaughn Kelso.

Extracted from a Washington Post graphic produced by Nathaniel Vaughn Kelso.The reality is that you have to attract residents with choices because you need property, sales, and income tax revenues to fund city activities. (Another perspective on this is Rolf Goetze's Building Neighborhood Confidence, written in the late 1960s.) I had written a few comments about this in a thread on the blog Urban Commons last week:

Center cities only having "neighborhoods of and for people who have no other choices" well, it's not a competitive advantage. I will say that his argument in some respects parallels some of the discussion in Logan and Molotch's Urban Fortunes about historic preservation.

I think the point that they missed is the necessity of stabilizing urban neighborhoods, including downtown, vis-a-vis the suburbs. You have to have viable neighborhoods (which requires "place-based" investments) in order to retain residents, residents paying property, sales, and income tax (if the jurisdiction assesses it). Retaining low income residents isn't great for either the revenue or expenses side of the city government financial statement...

The more people you retain in the city that are middle and upper income the better, because you need the revenue, badly. Detroit has such a tremendous infrastructure left over from its days as a city with 2 million residents that its property taxes are sky high. A house assessed for $200,000 pays $8,000/year in property taxes. That's 3x higher than DC! And it's not like Detroit is full of amenities. (Although a house assessed for $200,000 in Detroit could be worth $600,000 in the right neighborhood in a strong market city.)

The problem is that while strategic investments are required in downtown and other areas, too often the bulk of the investments go downtown, or to big projects, that in the great stream of things, aren't necessarily strategic in terms of generating additional private investments and in-migration of residents.

It's a hard issue to work through. "Neighborhoods first" policies often don't generate the kinds of revenues cities need, especially if cities are still leaking business and population, particularly residents that pay more in tax revenues than they consume in services.

But too often, the downtown first interest groups have hogged the majority of the public investments.

The other problem, and in terms of Mallach's talk yesterday, it was the one thing he didn't discuss and his presentation suffered for it:

Most elected and appointed municipal officials still focus on big projects, with an urban renewal mentality, even though for the most part, as a theory of revitalization practice it is safe to say that it hasn't worked and is discredited. (Also see Peter Drier's nice piece on Jane Jacobs, "Jane Jacobs' Radical Legacy," from Shelterforce, the magazine published by the National Housing Institute, where Alan Mallach is the research director.)

A giant wrecking claw releases a torent of debris as demolition of the 100-year-old apartment building begins. It will take six weekends to complete the razing.(Sun photo by Doug Kapustin) Sep 16, 2006

A giant wrecking claw releases a torent of debris as demolition of the 100-year-old apartment building begins. It will take six weekends to complete the razing.(Sun photo by Doug Kapustin) Sep 16, 2006This is a particular problem in Baltimore. I have been meaning to write a blog entry about how demolition of the Rochambeau building started last weekend, see "Building gives up ghost: The Rochambeau feels the wreckers' touch as a long battle to preserve the structure ends," as well as this story, "City houses to be razed," both from the Baltimore Sun. The latter story is about how 400 houses will be demolished across the city, to assemble land and develop larger parcels for development.

Crazy. Rehabilitating the houses and renting or selling them, or putting them into a community land trust would more likely "produce" affordable housing than their strategy. Plus it would likely be cheaper, especially given the quality and longevity of new construction, have higher appreciation possibilities, and it would maintain historic building stock in a way that strengthens Baltimore's identity.

See the National Trust report Affordable Housing and Historic Preservation: The Missed Connection by Donovan Rypkema, for more about this issue.

It makes me concerned about Martin O'Malley as governor of Maryland... Although from a "smart growth" and pro-transit standpoint, it'd be hard to be much worse than Governor Erhlich.

Mayor Martin O'Malley, left, and Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. debate at an event today hosted by the Maryland AARP in Timonium. At center is Joseph DeMattos, state director for AARP. (Sun photo by André F. Chung) Sep 14, 2006

Mayor Martin O'Malley, left, and Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. debate at an event today hosted by the Maryland AARP in Timonium. At center is Joseph DeMattos, state director for AARP. (Sun photo by André F. Chung) Sep 14, 2006See today's Sun editorial, "Smarter treatment." From the editorial:

But these upgrades can also allow sewage treatment plants to expand capacity. Reducing pollutants is good. Even expanding capacity is probably helpful. After all, if Maryland is going to have growth, better to have it hooked to a public sewer than a septic tank. Unfortunately, that's where matters get complicated.

Chesapeake Bay restoration grants are designed to clean up the worst polluting plants. The Maryland Department of the Environment doesn't factor in how the communities may potentially misuse any increased capacity. As a spokesman for the department told The Sun, "We don't look at what they do afterward." Controlling growth is considered a local matter.

That's a mistake. And it's another example of how the Ehrlich administration has repeatedly missed opportunities to build on Maryland's Smart Growth legacy. The Smart Growth concept demands that the state take a more active role in planning; without it, the MDE and other state agencies are merely enablers of bad local planning decisions.

The competitive advantages that cities have are centered upon historic architecture, urban design, and history (along with good transit). When you destroy historic architecture, you diminish your identity and your ability to compete. Granted if Baltimore were Detroit, the situation would be different. But it is well located, on the East Coast, well connected to other cities with rail, and in the core of a growing region, not to mention convenient to people priced out of Washington--the commuting distance by railroad to DC from Baltimore is less than that of many people who work in New York City but commute from other parts of New York State, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

But the average city official or planning department employee is shell shocked, and think that their best course of action is demolition. Sure their city has shrunk greatly. But nothing like Detroit.

As Alan Mallach said, "People aren't really buying houses, they are buying location."

If you wreck the advantages of your location, people won't be buying houses and choosing to live there.

Index Keywords: urban-revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home