The Washington Post Editorial Page fails to understand transit and/or mobility

Based on the op-ed piece by Fred Hiatt, editorial page editor, on page A15 of yesterday's paper, "Clogged Arteries," subtitled "We could solve the traffic mess. Here's why we haven't." Hiatt comments favorably on the recent book by Balaker and Staley, synopsized in an op-ed piece in the Post Outlook section on 1/26/2007.

That was a lousy article which I responded to in this blog entry, "Ideology and reality in planning and living in real places," as well as in this entry, "The Real Congestion Coalition," written in response to the same claptrap that appeared in the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review (a paper with an editorial agenda comparable to the Washington Times).

Hiatt writes that the major myth is that congestion can't be fixed.

Really the major myth is that anyone who wants to can drive a car whenever they want and that the roads to accommodate them can be easily provided.

Ed Risse, of the Bacons Rebellion website about Virginia Politics, calls this the "Private-Vehicle Mobility Myth." He's written about it in “The Myths That Blind Us,” October 20, 2003, “Clueless,” January 19, 2004, and in “Self Delusion and Fraud,” June 7, 2004.

He describes the Myth as:

"Regardless of where they live, work, seek services and participate in leisure activities, citizens believe that it is physically possible for the government to build a roadway system that allows them to drive wherever they want to, whenever they want to go there and arrive in a timely and safe manner.

The Private-Vehicle Mobility Myth helps parents convince themselves that the house with the “big yard” may be a long way from where the jobs, services, recreation and amenities are now, but that will change. Politicians reinforce the myth by continuing to promise that “soon” they will improve the roads and the big yard owners will be able to get to wherever quickly."----

Reality:

In one hour, one road-mile of road-lane can accommodate about 2,000 cars on a limited access freeway, and from 800 to 1,300 cars in various non-freeway situations.

The same lane mile can accommodate 6,750 people riding buses, 10,000 people riding bus rapid transit, a minimum of 15,000 people riding light rail, and up to 65,000 people in heavy rail (subway).

The average suburban household makes 15 trips per day, most by automobile, with limited numbers of additional passengers during each trip.

There are 5.2 million + residents in the Washington region. Let's say there are 3 million households. That means that there are 45 million daily trips in the region.

It's probably impossible to calculate the number of road miles required to allow for uncongested driving in such a scenario.

Hiatt, like Balaker and Staley, and like Wendell Cox, who has a letter to the editor in yesterday's paper as well, focuses on national averages, when national averages are irrelevant to Washington, DC.

In regions with excellent transit systems, significant numbers of people ride transit. (This includes DC, Chicago, San Francisco, NYC, Philadelphia.)

In a city like San Francisco, as many as 60% of daily trips to the Central Business District occur on transit. In Washington, upwards of 700,000 riders take the subway, and about 500,000 additional riders use buses.

In the City of Washington, approximately 40% of resident households do not own cars. (I don't know what the numbers are for Arlington County, but they are probably similarly positive.)

Residents of the City of Washington and Arlington County, Virginia have commuting times at or about the national average, while residents in the other counties in the Washington region have commuting times significantly higher than the national average.

It's reasonable to assume that this occurs in part because in the region, Washington and Arlington enjoy the richest set of non-automobile based transportation and mobility assets--plus in many areas, walkable communities. (Note that Montgomery County actually has a decent transit infrastructure, but not as good as DC and Arlington.)

Something Fred Hiatt needs to learn about is induced travel demand. For every 10% increase in road miles, there is a 9% increase in Vehicle Miles Traveled. See "Induced Traffic and Induced Development."

Something Fred Hiatt also needs to learn about is the "accessibility planning paradigm" used in the Netherlands. See "Utrecht:'ABC' Planning as a planning instrument in urban transport policy."

Also see "Transit-First Planning and Funding Policies" from the Transportation and Land Use Coalition of the Bay Area.

--------

Anyway, the reason I am "underblogging," is that I have a cold, I'm working, and I'm writing my class paper on building a "Transit First/Pro-Mobility" land use, transportation planning, and zoning regime based in part on SF's "transit first" policy which is built into their Municipal Charter; the accessibility planning paradigm in the Netherlands; and weighted parking requirements for buildings as implemented by a number of German cities based on the transit infrastructure in proximity to the building.

In short, the argument is that in sprawl and in an automobile dependent planning and development paradigm, center cities again possess competitive advantage in travel efficiency compared to the suburbs, provided at each and every opportunity, mode shift planning and transportation demand management are foremost on the land use agenda.

And while road capacity cannot (for the most part) be increased in a traditional center city, there are many opportunities to increase the capacity and efficiency of the transit and transportation "system".

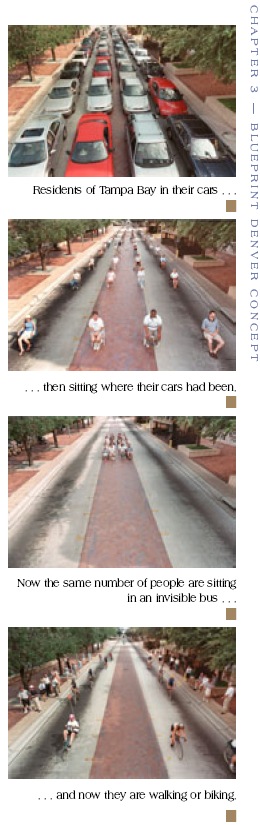

7/18/99 issue of the Tampa Tribune. Feature is called "Packing Pavement." BTW, there are 40 people shown in each image.

Image courtesy of Dan Malouff.

Labels: transit, transportation, transportation demand management, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home