Transit cities invest in transit expansion

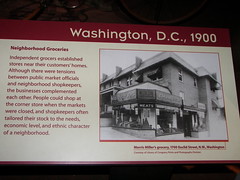

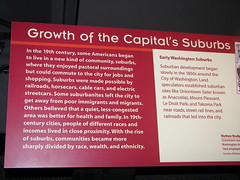

Narrative board, America on the Move exhibit, Smithsonian Museum of American History

One of the other things glaringly wrong in Steve Eldridge's columns last week about streetcars in the region is his comment that streetcars weren't a significant part of the transportation system.

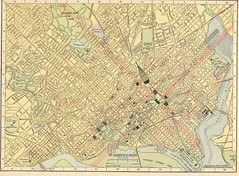

The reality is that the center city is defined by two eras, that of the Walking City (1800-1890) and the Transit City (1890-1920). Of course, streetcars existed from the 1860s, starting with horsedrawn cars. But it wasn't until the invention of reliable electric streetcars that the era of Transit City began. Fortunately, the urban form of the Walking City perfectly accommodated streetcars. The classic paper on the subject is by Peter Muller. "Transportation and Urban Form: Stages in the Spatial Evolution of the American Metropolis," appears in the 2nd and 3rd editions of the textbook Geography of Urban Transportaton.

Interestingly enough, the temporarily closed Smithsonian National Musuem of American History has a fabulous (for the most part) exhibit on transportation. A nice little chunk focuses on Washington area transportation from about 1900 to 1930. But it's not necessary for the exhibit to have focused on Washington to be correctly explanatory about transportation history and the impact on center cities as the regions beyond the city limits became the focus.

Speaking of exhibits, in 2002, the National Building Museum had a great exhibit on transit in the region. I'm thinking that Steve Eldridge saw neither exhibit. See "On Track: Transit and the American City," from the NBM site.

Interestingly enough, John Norquist, president of the Congress for the New Urbanism, wrote about these kinds of issues, in reference to Chicago, in "Chicago can't compete without good trains," in the Chicago Sun-Times. From the article:

What do Tokyo, London, Paris, New York, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Dubai have in common?Yes, they are all world financial centers with which Chicago both cooperates and competes in today's fast-paced global economy. And yes, several of them are Olympic cities, an elite group Chicago very much wants to join. But here's another key similarity: They are all investing billions in fast and efficient transit service. And that is where they part company with Chicago.

More recently, I have been making the argument that just as in the Walking and Transit City eras, DC has a renewed competitive advantage in mobility vis-a-vis the region, because the Walking-Transit City we are today affords mobility advantages over ever engorged suburban arterials and freeways--as long as all of our government policies in transportation, land use, public asset management, and location decisions are shaped to ensure that the City of Washington simultaneously achieves mobility and accessibility improvements.

Speaking of needing to understand and be familiar with transportation history before writing about it in an uninformed matter, there is a new book out on the subject that I definitely want to read, by Paul Mason Fotsch, entitled Watching the Traffic Go By: Transportation and Isolation in Urban America. H-Urban ran a review on the book this past week. From the review:

It is all but forgotten that for a brief moment at the beginning of the twentieth century the interurban trolley system was a rival to the automobile. Using articles in McClure's, Munsey's, and other popular magazines, Fotsch's first chapter shows that Americans welcomed the trolley because it offered an escape from the unsanitary conditions associated with horse cars, was quieter that the train, and took riders to more places than the railroad ever did. In contrast to the anxiety-inducing city, the trolley promoted something that popular writers called "brain health. "Why, then, is America covered with freeways rather than trolley lines?

Fotsch thinks that part of the reason is that publicists for the automobile made a successful appeal to the mythology of small-town individualism. The trolley was often crowded--and often crowded with the poor inhabitants of immigrant neighborhoods. The automobile offered a sense of individual autonomy. It gave teenage boys something to tinker with and prepared them, said the magazine writers, for adult responsibility. Highway construction, moreover, seemed free of the political corruption that still plagued trolleys. The moment of balance between trolley and automobile was brief. It soon seemed clear to urban reformers that their real challenge was to realize the promise of the automobile.

(Interesting, I have read articles from Collier's Magazine from the 1920s that made the case for chain store development because of the chaos of all the little independently owned shops that typified commercial districts at the time. This is an article in part about shaping the development of an economy structured nationally rather than locally, and the making of a mass market.)

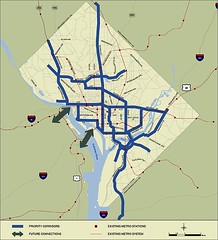

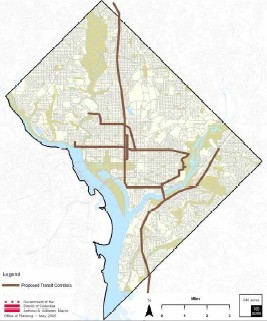

Between the end of the streetcar planning iteration (DC Transit Future) and the writing of the DC Comprehensive Plan's Transportation Element, 4 of the 8 proposed lines were dropped. The challenge with bringing streetcars back to DC is the creation of a true streetcar network, rather than just a collection of lines.

National Harbor image from the Washington Post.

I say this is the case given the City's focus on extending the under construction line to National Harbor in Prince George's County. How is improving the connectivity of a major development that is designed specifically to cherrypick business from the DC hospitality industry a benefit to the City of Washington's economic and transportation development?

We need to set DC-centric transit expansion priorities and act accordingly. (A way to think about this is to consider the San Francisco MUNI system for SF vis-a-vis the regional BART subway system as the streetcar system and the WMATA subway stations within DC as an equivalent of the MUNI system vis-a-vis the broader WMATA system.)

It is not that I think that including the surrounding counties in the development of the streetcar system is a bad thing, but I believe that priorities must be set, and the setting of priorities must be based on:

1. Reducing automobile trips into the city;

2. Improving mobility;

3. Improving accessibility.

To me, that would mean extending transit out (1) Pennsylvania Avenue SE, (2) up Rhode Island Avenue into PG County, (3) perhaps out Michigan Avenue, Queens Chapel Road, and Adelphi Road to College Park, (4) up Wisconsin Avenue, (5) past the Silver Spring Metro Station, (6) popping the H Street-Massachusetts-K Street-M Street streetcar line into Rosslyn, etc.

These are far more important to maximizing the City of Washington's mobility and accessibility objectives compared to an extension to National Harbor.

----------

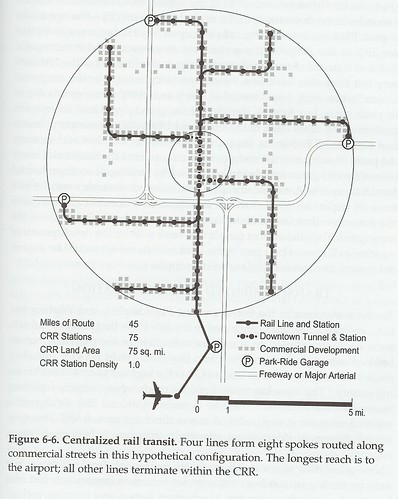

From "Accessible Cities and Regions: A Framework for Sustainable Transport and Urbanism in the 21st Century," by Robert Cervero:

Accessibility – as an indicator of the ability to efficiently reach oft-visited places – has gained increasing attention as a complement to the more traditional mobility-based measures of performance in transportation planning, such as ‘average delays’ and ‘levels of service’...

Accessibility is a product of mobility and proximity, enhanced by either increasing the speed of getting between point A and point B (mobility), or by bringing points A and B closer together (proximity), or some combination thereof. In this sense, an accessibility based approach gives legitimacy to land-use initiatives and urban management tools.

Compact, mixed-use development, such as embodied in New Urbanist communities and Transit Oriented Development (TOD), can substitute for physical movement by both shortening travel distances and prompting travelers to walk in lieu of driving (Ewing and Cervero, 2002). Some observers have referred to this as “trip de-generation” (Whitelegg, 1993).

DC Transit Future map of proposed streetcar lines, 2004.

DC Comprehensive plan map of proposed streetcar lines, 2006.

Map of Washington, DC , 1908, showing streetcar lines, railroads, and steamship docks (Hammond Company).

Labels: compact development, mixed use, transit, transit oriented development, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home