Historic preservation

One of the difficulties with historic preservation issues is coming to terms with two very different aspects. The first, and most commonly understood, is preserving the history of great men, women, peoples, and sites--e.g., Mount Vernon, George Washington's mansion and plantation, Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson, the Great Yellowstone National Park and the wonderful geysers, the Grand Canyon, etc.

The other is the history of the everyday, but that as a whole is unique, and also tells the story of neighborhoods, communities, cities, regions, states, and the country as well.

I call this kind of historic preservation preserving the nexus of architecture (mostly buildings), place (including urban design), and history (people). Another way to think about this is the concept of the cultural landscape.

This is the type of preservation most often associated with the creation of historic districts, especially of neighborhoods. Two concepts are key: (1) the period of significance--the time period for which the history of the neighborhood, including the predominant architectural styles, is significant in terms of preserving and recognizing the neighborhood; and (2) the context of the built environment.

Another important concept is what does historic mean? For many people, it is a legal definition, if a building or neighborhood is legally designated historic, then it is historic and is to be protected. If the building or neighborhood is eligible for designation as historic, but isn't designated, is the building or neighborhood worthy of stewardship, or just a bunch of buildings able to be altered beyond recognition?

The typical person unfamiliar with the details of preservation tends to miss the subtleties in all five of these concepts:

-- history is only of Great Men and Women, Events, and Noteworthy Places vs.

-- historic preservation and the nexus of architecture, place, and history;

-- period of architectural/historic context;

-- context;

-- "historic" as a legal definition only.

(The other important concept I didn't mention is the concept of architectural integrity--does enough of the building remain in its original state for the building to be designated as a historic resource, either on its own, or as a contributing resource to a greater whole. In other words a typical neighborhood house isn't architecturally significant on its own, but as part of a greater neighborhood, and should be interpreted within the broader context.)

The point about period of significance is particularly important--it's why you can make decisions about specific designs--design is more than just a matter of aesthetics or opinion*--because they are based on the period of significance for a neighborhood, the history of the architecture and pattern of building, etc.

* Part of the problem here is people's own level of intellectual complexity. For people who reason at lower levels, they are often stuck in relativistic thinking patterns, and believe that everything is relative, that there aren't specific merits to be considered that lead to particular kinds of decisions. See "WILLIAM PERRY'S SCHEME OF INTELLECTUAL AND ETHICAL DEVELOPMENT" for more on this broad point.

The other point is context, including urban form, not just building form. Based on urban design principles, you can make assessments and judgements about whether or not proposed projects fit.

This comes up because of the letter to the editor in the Post, "Sending Apple Back To the Drawing Board," about the Apple Store in Georgetown matter ("Apple Store Design Hits a Glass Wall Again" from the Post) which I have written about previously. Jeff Leitner of Bethesda writes:

... What is historic preservation really all about? I had naively assumed the goal was to preserve old buildings of historic significance from the ravages of modernity. But the building Apple intends to raze is 24 years old. As I understand it, the board doesn't even concern itself with the interiors of these allegedly historic buildings.

What is clear to me now is that historic preservation is about creating a facade of history without particular regard for the history itself. This is dangerously close to a homeowners' association telling a homeowner that she cannot plant a particular kind of bush in front of her house. So is historic preservation really only about a few uptight architects trying to foist their superficial sense of architectural fashion on the rest of us?

No it's not about architectural fashion, it's about architecture based on the period of significance, urban context and appropriate urban design. And context includes concerns about the "viewshed" and broader streetscape.

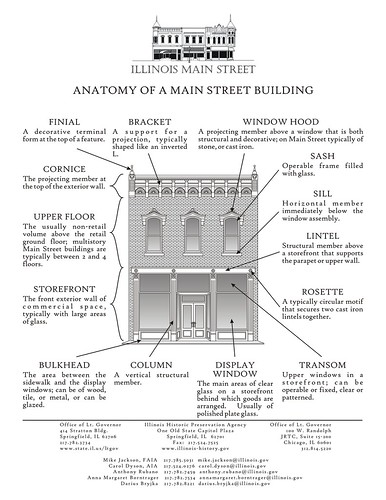

From the standpoint of Georgetown, it's about buildings with ground floor facades that look more like this.

While I do believe that the Apple Store design recently proffered is not completely unreasonable, it is a 100% glass storefront which is out of context for Georgetown, although not for a shopping mall (which has a different period of architectural significance). People with greater familiarity with Wisconsin Avenue's viewshed, for this building, the significance comes from looking west from vantage points such as Book Hill at R Street NW, argue that the virtually all glass front of the building, due to the particular location of this site, is particularly inappropriate.

Design 4, Apple Store, Georgetown.

Macy's store at Citi Plaza, Los Angeles. AP photo by Damian Dovarganes.

While the front entryway of this Macy's store is not glassed in, it is similar to the design offered by Apple in their most recent proposal. The antecedents are clear, demonstrating that the design offered by Apple is more appropriate for a shopping mall, not for a storefront on a traditional commercial district streetscape.

Georgetown.

This comes up also because of this interesting article in the Pacific NW Magazine supplement of the Seattle Times, where the residential design writer mulls over 20 years of writing, and recognizes that "Preserving our unique Northwest neighborhoods is everybody's business," that it's not about fashion, but not just about history either, but also about sound economic and eco-friendly decisionmaking.

From the article:

As I've tried to educate people here about the value of the region's history, its built heritage and the many good stewards of older homes, I have also gained a great deal of knowledge about buildings, neighborhoods and personalities that I might otherwise have missed. In particular, it has been a privilege to talk with homeowners whose love for their homes mirrors my own passion. ...

Unfortunately, for all the older homes in the Puget Sound area that have worthy stewards, many more are neglected or insensitively remodeled. Others are razed for bigger, more up-to-date, but not necessarily better, fits in traditional neighborhoods. Hardly any of the houses I have written about in 20 years are designated city landmarks or are in historic districts, either of which would offer some degree of protection and oversight for their futures.

Preserving our residential heritage is everyone's business. It's not simply a regulatory function of city government. Landmark designation and historic-district protection are only partial solutions for addressing the broad-based challenges of preservation in a market economy that sees dollars in the developable land — not the building on top of it. The question of how the landmarks process affects land use will continue. I'm hoping that, with education, property owners will not see the process as punitive but as stimulating to both creative ideas and a better ethic of neighborhood planning.

BENJAMIN BENSCHNEIDER / THE SEATTLE TIMES. Traditional housing stock, century-old trees, formal boulevards and less-formal planting strips and greenbelts such as this streetscape in Madrona are elements that make Seattle's historic neighborhoods so appealing. Conserving irreplaceable resources while allowing new construction requires striking a balance which recognizes that larger is not necessarily better.

It is true, as Mr. Leitner writes, that for the most part building interiors are not "regulated" under historic preservation guidelines. The same is true, for the most part, for grounds. Maintaining "historic" interior features is a matter of individual stewardship, and something I've become more conscious about since we moved to a 1929 bungalow near Takoma DC, a house that has only had 2.5 owners + us, in its 80 year history.

While we haven't tracked down the full history of the house yet, at some point in the 1930s probably, a family including their adolescent daughter, moved into the house. That daughter stayed on in the house until she died at the age of 94. And for the most part, the house stayed the way that it was originally built (some changes occurred in the living room and front bedroom), even the original keys for the bedrooms and bathroom are still here, never having been remodeled

And not having been remodeled, the house's timeless qualities have been preserved (and except for one replacement bathroom sink--since replaced--nothing significantly inappropriate was ever added), making me much more interested in the interior side of historic preservation, and doing necessary changes in a manner that also respects the "architectural period of significance," "building materials," and "context" of the house.

I have to admit there are a couple things we want to do that a preservationist might not agree with--we'd like to put a bungalow-type porch on the house, which unlike most every bungalow ever built, was not constructed with a full length front porch--but since such a porch was never built on this house, you can argue that doing so now would be an inappropriate modification. But all in all, we will be stewards of the house, just like the previous owners. None of this is merely "architectural fashion."

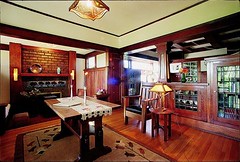

Our house is pretty simple and straightforward. It does not have the kinds of interior architectural details such as this house in the Wallingford neighborhood of Seattle.

The lead photograph of the Oct. 9, 1988, Northwest Living feature showed the living room of the Paul Parks bungalow in Wallingford, furnished with sturdy oak furniture. Unusual interior features include the divider pillar that doubles as a colored-glass lighting fixture, and the gold glass mosaic fireplace surround with tree motifs. CRAIG FUJII / THE SEATTLE TIMES FILE

Labels: historic preservation, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home