Urban design, sprawl and the automobile

SE-SW Freeway under construction near the Marine Barracks, 1971. DC Dept. of Transportation photo.

The Weekend Financial Times has an article, "Highway to hell revisited," about the negative impact of the Interstate Highway Act on the country in terms of sprawl and gasoline dependence, and how President Obama has praised this act. (You'll have to register for access.)

It discusses how most highway advocacy is directly or indirectly supported by the consruction industry, and how for the most part, the Interstate Highways led the destruction of cities both in terms of cutting up neighborhoods through the construction of various routes as well as the roads serving as the way out of the city to live, but back to the city for the best jobs.

A tanker truck carrying 8,700 gallons of gasoline burns after exploding this morning on Interstate 95 north of Washington, D.C. The driver was able to escape unharmed after he noticed one of his rear wheels burning as he headed south from Baltimore.(AP photo)Nov 23, 2005

The article, by a columnist who is an editor for the Weekly Standard, also discusses how government projects aren't always a good thing. There is a lot to be said for this belief. We need to differentiate between projects that add value or projects that destroy value. As much value has been added by the creation of a robust freeway network, as much may have been destroyed in terms of building an economy dependent on automobiles, gasoline, and roads.

(Also see, from 2008, "On the pot-holed highway to hell," also from the FT.)

From Scott Doyon--Re: the depiction of urban environments in media directed at children, my six year old daughter recently brought home a book from her school library called The House Book by Keith DuQuette. Included in it, following a lot of nice traditional home illustrations, was the attached depiction of city to country. It's so good for what it is, I was surprised it didn't have a DPZ credit at the border. My daughter understood it immediately. There is hope.

This question is also relevant to intra-city issues in the center city. David Alpert, of Greater Greater Washington, opines about opposition to significant changes to the philosophical and regulatory provisions of DC's Zoning Code, in "Zoning update opponents attack Office of Planning."

Surprisingly, the Zoning Commission is open to the idea that the Zoning Code should be supportive of urbanity, rather than a slight rewrite of the suburban oriented Zoning Code that DC first imposed in 1958, and has modified since. (this process started in response to the revision of DC's Comprehensive Plan in 2006).

This change is sparking reaction in many quarters. A lot of the reaction either directly or indirectly ends up supporting automobile-centricity, which I find incredibly ironic and sad.

Like David, I have written about what I think is the source of this reaction. Many of the city's long time and "traditional" activists took up their efforts during the many decade period when the city was in financial exigency and the population continued to shrink. These residents help stabilize and maintain neighborhoods that otherwise would have been disinvested.

This is one of the reasons by the way that I am such a fervent historic preservationist. There is no question that historic preservationists "saved" the city during those long decades when behaviors and trends did not favor urban living. The same laws about preservation that people revile today were the laws that saved many neighborhoods from possible destruction, or at the least, significant disinvestment. Those efforts should be respected and extended, by continuing to practice historic preservation by extending the provisions and protections to more places within the city.

Anyway, I think a useful way to approach how we do things _in the city_ is to be aware of how the city was constituted, on what principles. In short, the urban design and development principles that characterized the city as it was first laid out by L'Enfant in 1791 and subsequently developed through two eras, that of the Walking City (1800-1890) and the Transit-Streetcar City (1890-1920), should be respected and supported via the Land Use Plan and Zoning Code of the 21st Century.

The primary aspects of the city's livability were created in an era without automobiles, and to continue to apply automobility based land use and design principles to fundamentally urban questions is a mistake and needs to be stopped.

It is unfortunate that yesterday's activists don't understand the underlying principles of what they were doing 40 and 30 years ago, and how those principles need to pay fealty to the urban question.

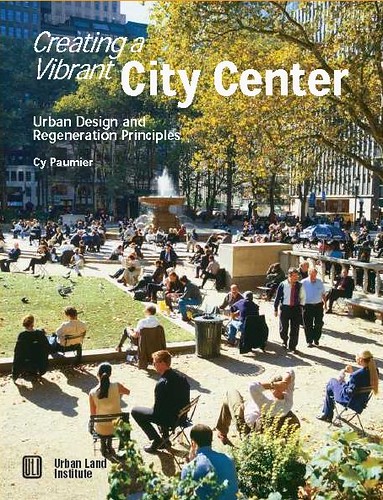

Cy Paumier writes in Creating a Vibrant City Center that the pattern of downtowns (central business districts) developed around pedestrian-scaled streets, blocks, and buildings because of:

Concentration and Intensity of Use: "The intensity of development in the traditional central area was relatively high due to the value of the land. Maximizing site coverage meant building close to the street, which created a strong sense of spatial enclosure. Although city center development was dense, construction practices limited building height and preserved a human scale. The consistency in building height and massing reinforced the pedestrian scale of streets, as well as the city center's architectural harmony and visual coherence." (p. 11)

Organizing Structure: "A grid street system, involving the simplest approach to surveying, subdividing, and selling land, created a well-defined, organized, and understandable spatial structure for the cities' architecture and overall development. Because the street provided the main access to the consumer market, competition for street frontage was keen. Development parcels were normally much deeper than they were wide, creating a pattern of relatively narrow building fronts that provided variety and articulation in each block and continuous activity on the street." (p. 12)

The street grid, transportation practices and construction technology of the times, and the cost and value of the land led to a particular form of development on city blocks that focused attention on the streets and sidewalks, creating a human-scaled, architecturally harmonious built environment.

As construction technology advanced and taller buildings could be constructed, and as the walking and transit city was supplanted by the automobile, the scale of block development changed significantly, with a focus away from the pedestrian and towards the car.

OTOH, because TOD proponents are usually working on greenfield sites or grayfield site adaptations, it doesn't have the same kind of antecedents as the type of development described by Cy Paumier as typifying the development of downtown and the close-in neighborhoods near to downtowns.

And note, the report-publication produced by Karina Ricks (now the deputy director of transportation planning for DC's Department of Transportation) back in 2002 when she worked for the Office of Planning, Trans-Formation: Recreating Transit-Oriented Neighborhood Centers in Washington, DC, is really quite good. Frankly, it's one of the best descriptions that I've seen lately of how to (re)do infill development and build stronger neighborhoods. (I never really worked through the tome when it came out because I wasn't working very much on transit issues then.)

------

Speaking of irony, I find that some of the most ardent anti-freeway activists from the 1960s have become--even though they wouldn't think so--ardent proponents for the car, because of their unwillingness to support land use patterns that favor walking, bicycling, and transit use, rather than automobile trips for getting around.

Labels: car culture and automobility, civic engagement, land use planning, progressive urban political agenda, sustainable land use and resource planning, transportation, urban design/placemaking, zoning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home