Reassessing historic preservation on account of it being National Historic Preservation Month

------

This blog entry is in part a reprint, but has been significantly augmented. Also see "This place mattered #1: May is National Historic Preservation Month" from last year.

This is a doctored image, based on the NTHP promotional campaign.

------

This pathetic looking sign (I added the border) is the sign blank provided to preservation advocates by the NTHP for the 2009 and 2010 National Preservation Month.

In 2008, the Hill Rag ran a piece, "May is National Preservation Month," stating:

As we celebrate National Preservation Month each May, there is no better time to reflect on why historic preservation matters to us as a community. Perhaps you are already an enthusiast due to your passion for architecture or your interest in community history. Maybe you are the devoted steward of a home here that you wish to see protected, or perhaps your interests are even broader, applying to such issues as city planning, zoning and transportation. It is possible – I concede – that historic preservation would not top your list of priorities at all if asked. However, in this age of global awareness, most everyone is concerned about the environment. And if you care about the environment, then you care about historic preservation.

The hottest topic in historic preservation today is undoubtedly sustainability, with experts and enthusiasts presenting the valid argument that an existing building is the greenest building of all...

So here's my chance once again to reflect on the issues facing historic preservationists in Washington, DC.

1. The theme of 2010's National Historic Preservation Month is "Old is the New Green." I disagree that the hottest topic in preservation is sustainability, even though that is all that Pres. Moe of the National Trust for Historic Preservation seems to talk about at conferences.

For example, the 2009 op-ed piece in the New York Times by Richard Moe didn't read right to me, it seemed far too apologetic, and didn't adequately address the issue of historic windows versus replacement windows. See "This Old Wasteful House."

That headline is death.

It encourages people to believe that "old" houses are not environmentally sound. That windows ought to be replaced with vinyl pieces of crap that fail in about 15 years...

Sustainability as a term is bandied about and people using it often have a narrow focus on very specific aspects of environmental issues, rather than a full and complete concern about sustainability in every dimension, including land use, embodied energy, urban systems, etc. From that standpoint, you can't beat preservation and historic preservationists have nothing to be apologetic about.

2. The conflict over property rights issues vs. historic preservation, in a variety of respects is the number one issue, and will continue to be for some time.

No historic district sign, Lanier Heights, DC. Photo from DC Metrocentric. The sign here flips around the argument that I use, "it's our neighborhood" and therefore how individuals do things contributes to or diminishes from the neighborhood, and that's a strong justification for preservation protections via regulation.Instead their argument is "it's our neighborhood" and we should be allowed to f*** it up however we want. Really they should be saying "It's my property, f*** you, I can do whatever I want."

Why is this ignored, for the most part, by the National Trust, when at the local and state level, preservation organizations are getting their a**es kicked on this issue?

3. The National Trust is up in arms over President Obama's proposal to defund two preservation programs, Save America's Treasures and Preserve America (both programs were associated particularly closely with President Bush and First Lady Laura Bush, which is usually a kiss of death if the succeeding administration is of a different political party) and cutting in half the funds to the National Heritage Areas program.

I hate to blame the victim here, but I think this is an indicator of the failure to better articulate the aims and necessity of historic preservation as a key economic development and quality of life tool for the 21st Century.

The Trust has had many many opportunities to do better on this issue, and they haven't. Eventually, you can't continue to cruise on goodwill alone.

4. While NTHP President Richard Moe has been quite good, he is retiring, and it will be interesting to see which way the National Trust moves in selecting his replacement. Relating to (1) and (2), I was critical of Richard Moe's speech at the National Building Museum in 2007, upon his being selected as the recipient of Vincent Scully Prize, because I thought he was presented with a critical forum and opportunity to rearticulate the value of historic preservation in the 21st Century, to lay forward the agenda for the next two decades, and he did not, instead speaking about (yes) sustainability, but not in a manner that tied it to broader concerns within preservation.

5. And the resulting political machinations in the historic preservation process. In DC, legislation has been entered to provide churches with waivers--ironic because churchly mismanagement of historic buildings led to the creation of the local preservation law in the first place--and to make it even harder to create historic districts.

In Montgomery County, Councilmember Michael Knapp entered legislation which would significantly weaken local law there. See "More than 30 speak against proposed changes to historic preservation law" from the Gazette. Fortunately, at this juncture the effort seems dead, see this web update from Montgomery Preservation. But it is still chilling.

The demolition of this building, located at the corner of 5th and East Capitol Streets NE by the Capitol Hill Baptist Church, to be replaced by a parking lot, led to the creation of local historic preservation laws, providing for local protections independent of federal historic preservation laws, which only pertain to federal undertakings.

6. In large part, this problem (besides the unfettered desire to do anything with your property, regardless of potential negative impacts on others), derives from the difficulty that many people have with what we might call historic preservation of the "every day" -- preservation of neighborhoods -- in the same way that they understand the preservation of buildings, sites, and places that relate in some way to what we might call "the grand forces of history." Remember that I call preservation of "every day" history the nexus of place, architecture and people (history).

7. The protection of buildings and neighborhoods that are eligible for designation but are not designated and won't be any time soon. This conflict has many dimensions: building up (pop ups) and out (what I call supersizing), inappropriate design of new construction, teardowns for extranormally large (and usually ugly) houses, no protections against demolition generally.

This simple bungalow two doors down from me is no more, having been replaced with some ersatz building that the owners think they will be able to sell because it looks suburban and is larger than the building it replaced. (Meanwhile, a similar supersizing of a house around the corner from us has resulted in a house sitting on the market for about two years, and a more than $200,000 reduction in the asking price.)

Before.

After.

8. Dealing with preservation issues where development pressures are extremely high, which is partly related to #3 but important in and of itself. The failure to protect historic integrity at the St. Elizabeth's Hospital Campus because of "jobs" is a good example of this problem. See "St. Elizabeths could lose historic status" from the Washington Business Journal and this op-ed by NTHP president Richard Moe in the Washington Post, "A Disaster for St. Elizabeths."

Although I think that for the most part, this is being appropriately dealt with by the General Services Administration, the fact that the DC City Council didn't stand up for historic integrity simultaneously with economic development is very disturbing.

For most center cities, preservation is the only long term sustainable strategy for resident retention and attraction. As far as the Central Business District goes, DC is an outlier. Pressures for office space and redevelopment mean that preservation, while essential in most other cities, such as Philadelphia or Baltimore, takes a back seat to development in the core of the City of Washington.

Also see as resources:

-- Affordable Housing and Historic Preservation: The Missed Connection

-- Economic Power of Historic Preservation (Paper)

-- Profiting Through Preservation (report/NY)

-- Contributions of Historic Preservation to Quality of Life in Florida

- Research Report Executive Summary

- Research Report - Technical

9. Related to this is the stewardship of the DC Government with regard to the properties it manages in trust for the Citizens of the District of Columbia, and the pressure to deaccession buildings and sell them off for new development. Many buildings are left to rot. My joke is that DC's primary property management goal is demolition by neglect.

10. Dealing with the whole "recent past" question. (i.e., Christian Science Church, MLK Library, etc.) The debacle over the Third Church of Christ, Scientist, is not likely to bode well for how preservation is perceived. Now a local federal judge is not favorable but that is in part because the local federal circuit is not very progressive.

The city agreed with the economic hardship arguments by the Church, even though an alternative development project was not proffered. Economic hardship is a slippery slope.

11. Institutions and others desiring exemptions from the preservation laws: i.e., the church question (RLUIPA), the Mt. Pleasant debacle (how to handle modifications to buildings to handle accommodations for the disabled), etc. (This is also related to #2)

12. And why doesn't Marc Fisher, the former columnist for the Washington Post, now the enterprise editor for local news, appreciate historic preservation, when there is no question that for the almost 40 year period in which most people with choices abandoned the center city, preservationists were the urban pioneers and/or the people who saved the city for the latecomers to enjoy today. Every thing he writes about preservation (such as "Chevy Chase DC Rejects Historic Status" or "Human Dignity Also Needs to Be Preserved") is negative, and though I like his writing generally, misleading, or at the least, inadequately nuanced. (Part of the problem is that the column and Marc is focused on the individual, rather than systems and processes and the overall impact of decisionmaking, what is called "death by one thousand cuts." You don't notice things when it happens one at a time.)

13. Preservation isn't just for whitey either.

From a past blog entry (Historic preservation and public history: whose history is history anyway?):

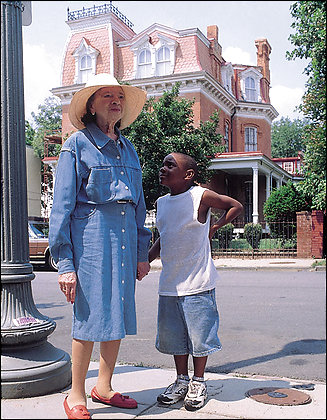

The Post reports the obituary of Theresa Brown, the "Theresa F. Brown Dies at 86; Advocate for Preserving Historic D.C. Neighborhood" -- but the headline in the paper is better "Tenacious Protector of LeDroit Park."

She led the effort to stabilize and improve the LeDroit Park neighborhood of Washington, DC, one that had been home to the city's "upper crust" African-Americans for many decades, but had declined along with other neighborhoods in the city due to population loss and then the impact of the riots.

From the article:

Hammered by the 1968 riots and the flight of both residents and businesses, LeDroit Park took on a shabby appearance. Homes were left vacant, drug dealers moved in, and Howard University's expansion ate away at the edges of the area. Mrs. Brown, who worked for the old Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co. and was one of the first black women hired for its Baltimore office, told whoever asked that although she couldn't afford to live in the best neighborhood, she could work to make her own neighborhood the best. So she set to it.

She formed the LeDroit Park Preservation Society and began educating residents about their area's history. The tree-lined streets and landscaped traffic circles remained, as did 50 of the original 64 large homes, featuring beautiful tile roofs and gingerbread trim, expansive chimneys, iron grillwork, solid wood porch columns, bay windows and high ceilings.

In 1974, the neighborhood became an officially registered historic district. Some of her neighbors thought it silly, Mrs. Brown told The Washington Post in 2001. "I didn't care what the neighbors thought," she said. "There weren't enough of them to get in my way. I just kept going."

Theresa F. Brown poses with a child in her beloved LeDroit Park, a neighborhood filled with history. (By James Kenah)

14. The height restriction. I am a hardcore preservationist, I think people know that. But looking at the height restriction objectively, there is no question that continued demand for commercial space downtown, and the inability to build up, means that developers build outward instead.

So what you have happening is the "reproduction of the space" east and southeast of the Central Business District. We're losing historic building stock and making business districts out of what were once neighborhoods.

Soon enough M Street SE and NoMa will look just like K Street NW--an onward spread of 12 story boxy glass buildings. Even the H Street NE corridor is under threat, depending on what happens with the Dreyfus project at 200 H St. NE.

The only problem with puncturing the height restriction is that it is too late. The damage to neighborhoods east and southeast of the Central Business District has already been done.

But in any case, it's a good lesson for considering all the consequences, including those unintended, of urban development policies.

15. Not to mention how undifferentiated property tax policies put smaller commercial properties at risk, especially in neighborhood commercial districts. I have written about this a lot:

- Testimony -- Historic Neighborhood Retail Business Property Tax Relief Act (2006)

- A solution for the overtaxing of properties in neighborhood commercial districts (2009)

- Displacement of retail businesses through increasing property tax assessments (2005)

- Forcing Displacement by the disconnection of tax assessment models from public policy goals (2005)

- Globalization of the DC real estate market catches neighborhood commercial districts up in the wake (2006)

- Avoiding the real problem with DC's property tax assessment methodologies (2007)

- The hot real estate market Downtown and Georgetown (2007)

- Even more on commercial property tax assessment policies (2007)

16. Local preservation organizational capacity, communications, and the need to attract the next generation of people to the movement. Most of DC's citizens groups have leadership that came to prominence during the time when the city was shrinking, and stabilization of neighborhoods was the most important goal. Now the city is growing, how do we as preservation activists, and how do our preservation organizations respond to this fundamentally different condition and situation?

This rare instance of the Historic Takoma organizational newsletter distributed at a neighborhood coffee shop is an example of something that needs to happen more often. It probably is there to promote ticket sales to the upcoming house tour.

Preservation promotion at the Sunday Takoma Farmers Market.

17. Relatedly, in the rise of the Internet and the focus on the power of the network is the failure to adequately leverage the power of the network of people and organizations focused on historic preservation in DC. Neighborhood groups need more support and capacity, but at the same time, by sharing resources across the "network" of preservation organization, more can get done.

18. Looking at the local preservation operation in DC Government, and comparing it preservation agencies across the county, I think we could do a lot more to articulate, communicate, and market the value of historic preservation both to the city and to individual property owners, but mostly as essential to the city's competitive advantage as a real, authentic, special place.

At Magical Montgomery, the Montgomery County arts festival, held in Silver Spring in September, the County historic preservation office has a booth. (Other county preservation groups had booths as well, including Silver Spring Historical Society, a group focused on teh Forest Glen Seminary, and others). Similarly, at the Arlington County Fair, the major county offices, including planning and historic preservation, have booths in the county aisle (and the county preservation organization had a booth elsewhere on the exhibit floor).

Display board, Montgomery County Historic Preservation Office, Montgomery Spectacular, Silver Spring, MD, 2006.

Display board, Montgomery Historical Society, Montgomery Spectacular, Silver Spring, MD, 2006.

I can't say I've ever seen much of this kind of outreach on the part of the DC Historic Preservation Office.

Sure the office reaches out to the activists or the enraged, but what about everybody else?

19. Many other historic preservation organizations elsewhere sponsor an annual "expo," sometimes as part of an annual conference, but focused on the practical, on how to take care of your historic (or eligible for designation) home. A particularly good example is the Historic Chicago Bungalow and Green Expo in Chicago. Last year, 8,000 people attended! Talk about building the knowledge and capacity of homeowners and interested stakeholders...

From the Historic Chicago Bungalow and Green Energy Expo website. Individual homeowners are acknowledged for their preservation-sensitive efforts.

20. Oh, and the street signs that DC uses to acknowledge historic districts are hideous.

There are many examples of sign toppers elsewhere that are much better. Some cities also list neighborhoods on the signs at major arterials.

These street signs on the border of the Bloomfield and Lawrenceville neighborhoods in Pittsburgh, list the respective neighborhoods.

21. And using the Silver Spring heritage trail as a model, why not provide all neighborhoods with gateway historic-heritage-cultural interpretational signage, so that people can learn more specifically about their neighborhood and why it matters, what the narrative themes are for the city generally, and how their neighborhood fits into the overall neighborhood, and how it contributes in special ways, what the nature of the building stock is, the development history, etc.

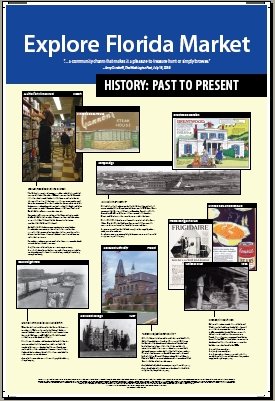

The signage prototype that Christopher Taylor Edwards and I created for the Florida Market is a good model for how this could be done with 2-4 signs, rather than a set of 19 signs as is done through the heritage trails program.

Labels: building a local economy, civic engagement, economic development, historic preservation, sustainable land use and resource planning

1 Comments:

Windows in Norfolk Virginia and their restoration is what my company primarily does. Vinyl windows are not always the answer as you have stated

Post a Comment

<< Home