Today's

Post has a piece, "

Battle looms over transportation mandate," about how the Republicans are railing against mandated spending on walking and biking as part of state transportation programming of federal transportation monies. From the article:

The looming Capitol Hill battle over transportation priorities in a budget-slashing era may have found its lightning rod issue: bike paths, pedestrian walkways and wildflowers planted by the side of the road.

The question is this: With the nation facing a transportation crisis that has gotten little attention outside of policy wonks and Washington, should the federal government continue to mandate that states spend federal dollars on pedestrian safety, bicycling trails, landscaping and historic preservation?

Like many of the issues that get marquee attention in the partisan warfare in Congress, its symbolism outweighs the actual expense. And singling it out brings to the fore substantial philosophical differences over how to target transportation dollars and to what degree Washington should be allowed to set state priorities.

The transportation enhancements portion of the federal transportation program is designed to focus on what we would call the placemaking opportunities inherent in transportation infrastructure, in linking transportation investments with land use planning and urbanism as a more focused economic development strategy.

Sure there is funding for transportation-related museums and bike paths and such, which makes it easy for people to criticize.

But the "complete streets" movement is derived from a number of different threads: balanced transportation, rather than an almost exclusive focus on roads and automobiles; shifting travel to more sustainable modes (walking, biking, transit);and doing so in ways that enhance places rather than reduce local quality of the life in favor of enabling traffic to move more quickly.

Rockville Pike, Montgomery County, Maryland. Washington Post photo by Bill O'Leary.

Presuming that people are willing to act logically, and most often they are not (you know the saying by Winston Churchill, "you can always count on America to do the right thing, after she has exhausted all the other possibilities"), problems come up in terms of getting to the heart of the matter.

I aver it has to do with flaws in our planning processes.

First, we don't have a national transportation plan, not really, where, like the equivalent of the

Goals and Policies section of the Arlington County Master Transportation Plan, various goals, sometimes conflicting ones, get discussed and defined.

Second, so a complete streets policy--one that balances transportation needs across all modes rather than exclusively focus on automobility--as a component of national planning isn't there so much, at least not in the minds of conservative members of Congress, even though there are the refigured agendas of the US Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, the Dept. of Transportation, and the smart growth initiatives of the Environmental Protection Agency (which is getting major pushback from the Republicans).

Third, we don't have "history" sections in our plans, partly because history is contentious. But the

Master Plan for the City of Baltimore does have

a history element, and while I think it is a little too positive about urban renewal, it's interesting in that it does provide context for decisions. Transportation plans need such sections big time, because there are so many myths about transportation practice that need to be punctured, if we are to move forward in a substantive fashion.

Fourth, the same goes for transportation finance, there needs to be a section on transportation finance in every master plan, and that goes double for a national plan. Until we make it clear how transportation infrastructure is funded--local infrastructure is mostly not funded by federal excise taxes, and it is mostly spent on interstate freeways.

For example, the myth that road construction and maintenance is fully covered by payment of gasoline excise taxes is one that needs big time puncturing.

The real problem is that people aren't willing to raise the gasoline excise tax, which in the U.S. is significantly less than in Europe. The federal gasoline excise tax hasn't been raised since October 1993. According to an inflation calculator, just to keep up with inflation, the rate should be 27 cents/gallon. (State and local gasoline excise taxes have been raised in various jurisdictions. Virginia resists increasing theirs, while Maryland is fighting a major battle over a 5 cent increase.)

As

Mother Jones Magazine says in "

The GOP hates bikes," "States spend only about 1 percent of all transportation funds on projects devoted to cycling or pedestrian improvements. Yet Republicans see this as an area ripe for cutting."

If you want to fully fund roads, pay for the military-related costs of access to Mideast oil, public health costs, other environmental costs, etc., without subsidy (see the Brookings report by Martin Wachs,

Improving Efficiency and Equity in Transportation Finance) then the gas tax has to increase not by cents, but by dollars.

With regard to walking and biking more specifically, I think that our bike and ped plans tend to be deficient also, in ways similar to our failures in lack of national plans and gaps in state and local transportation plans more generally.

The National Household Travel Study (

League of American Bicyclists blog entry) finds that 64% of trips are 5 miles or less. About 25% of trips are one mile or less, and with the right infrastructure, can be achieved by walking or biking. 26% of trips are from 1 to 3 miles. And 13% of trips are from 3 to 5 miles.

With the right infrastructure, many of these trips can be shifted from automobile to bike. Or to transit.

And not only is it less expensive to support bike and transit trips (it seems like transit is more expensive but it isn't, because 3 cars take up the space of one 40 foot long bus, etc.), it is more efficient to do so, and in the places where walking, biking, and transit is optimized, such as in the core of Washington, DC, you find--except for a handful of streets which are major entry and exit points into and out of the city and they tend to be congested often, such as New York Avenue--that there isn't all that much congestion--roads are relatively empty.

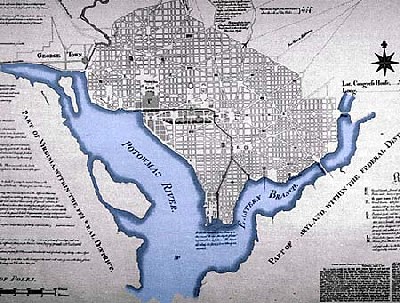

Of course, this is aided by the city's dense street network which is organized in a grid fashion, with small streets, lots of alternative routes, and radial avenues which provide direct routes to and from key destinations and activity centers.

L'Enfant Plan for the core of the City of Washington, 1791.

But for the most part bike plans don't discuss this to the level it deserves, nor the research findings of Roger Geller ("

Portland's Bicycle Brilliance" from the

Tyee) which state that of the 70% of the population that is willing to bike for transportation, only 10% does so, because the other 60% fear riding in heavy traffic and/or fast traffic--but with the right kind of infrastructure they will ride.

Instead, plans talk about all the infrastructure that is needed (and not enough on programming, but that's another issue), and when infrastructure is built it's done at the schedule and convenience of transportation departments, which usually retrofit bike infrastructure--if they do it at all--when they are rebuilding/resurfacing a road, rather than prioritizing bike infrastructure improvements in those places where biking is most likely to occur.

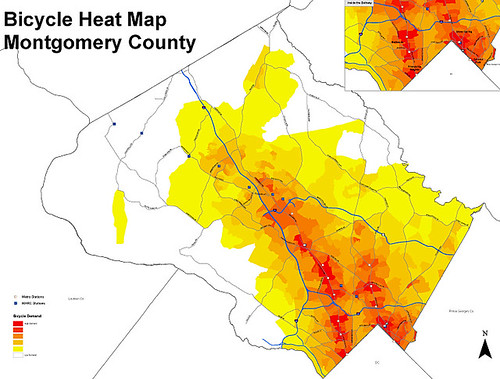

One way to show the difference in approach is to look at the (in draft)

Montgomery County "heat map", which shows the places where biking is most likely to occur, based on population density, route options, and proximity to key destinations.

That's where bike infrastructure should be prioritized, but that's not the way it works for the most part.

So bike infrastructure is put in various places, based on the convenience of DPW/DOT planning, and not in what we might call the Biking Mode Split Opportunity Zone, and when bike infrastructure doesn't get used, because it has been installed in places according to the master plan and convenience of the DPW, but not in the places where it would be more likely to be used, people who are more likely to support transportation investments in automobility are quick to criticize the "waste" of spending money on bike lanes, when the real problem is that we aren't building bike infrastructure in the right places, where we know it will be used.

As long as this continues to occur, we are going to have problems with transportation funding being directed to bike-related uses.

-- Sen. Tom Coburn, Oklahoma, calling bike/ped funding pork and trying to get such funding removed from federal transportation funding in

2007, in

2009, and in 2011.

Of course, it doesn't help that people like Rep. Kingston and Sen. Coburn think of bikes as toys and not something you use for transportation. Rep. Kingston is from Brunswick, Georgia, where bike as transportation is more difficult. They might bike recreationally, but have no conception of biking as transportation.

As long as they don't focus rightly on biking as transportation, they are going to continually advocate in favor of the car.

And in the meantime, it's up to the sustainable transportation community (planners, advocates, etc.) to rework our processes and plans to make our points much more directly and clearly.

Labels: bicycling, car culture and automobility, sustainable land use and resource planning, sustainable transportation, transportation planning, walking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home