The fifth phase of center city revitalization (reprint)

It's worth reprinting this entry, from September 2006. For the most part, I believe that the text holds true today (in December 2011) for those center cities on the East and West Coasts that are holding their own, relatively speaking, despite the 2008 real estate crash.

Froma Harrop of the Providence Journal has a column from the last week, "Congratulations Seattleites, you live in a cool city," about what's driving this, young people's desire to live in interesting places. (I am a proponent of face-to-face connection and agglomeration economies, so I believe her thesis.)

She jokes somewhat in the piece that young people are going to live in these places, even if there aren't jobs there (which is the joke behind the IFC series "Portlandia"). This is fueled by having a decent supply of relatively low cost housing which supports shared housing, etc.

I am not part of that segment of the housing market anymore, but wonder how much of it still remains in DC...

--------------------

Entry: Tuesday, September 19, 2006

The other thing that I thought about in terms of Mallach's talk and my own learning, some recent planning history and theory I've been reading, my reaction to a particular part of a presentation at a preservation fundraising training held last Saturday, and my continued incredulity about the failure of current residents to understand the antecedents of city livability, is phases of urban revitalization since just after World War II.

Outmigration from center cities was pretty much halted by the Depression and World War II, which diverted most resources to the war effort. But the process of outmigration started decades previous to the Depression, mostly enabled by railroads and then streetcars, but made relatively simple by the car, especially as a reliable road and service network developed.

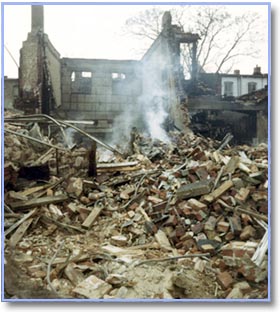

After the War, the pent up demand of the American consumer was released. And rather than work to rehabilitate the cities, which experienced a good 16 years of disinvestment and it showed--many residents chose to leave the city and move into greener pastures.

The five phases of urban revitalization:

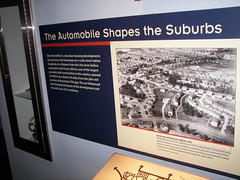

1. Urban renewal and a focus on accommodating the car. For centuries cities were designed around walking. The horse, carriage, and stagecoach were the most advanced technology for getting around. Cars changed everything. The ability to conquer distance changed everything, and scale and use of space changed dramatically.

The construction of the Interstate highway system should be considered part of this movement although it was more about enabling suburban development. Highways for the most part raped the center cities, which have not been able to recover still.

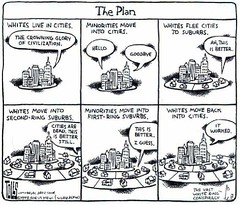

People moved out of the city, seeking the "American Dream" and a bit of lawn, but still worked in the city. Suburban development was mostly focused on retail and housing. As urban neighborhoods were cleared for "renewal" and "renewed" other city neighborhoods were destabilized by receiving the dispossessed which challenged neighborhood social networks.

From the 1960s, until the last decade, most urban sociologists believed that cities were born, grew, declined, and died. There was no sense within academia that center cities could revive.

2. The historic preservation movement in the early 1960s. People, attracted by the historic building stock in many urban neighborhoods, moved to the city. Center cities had changed significantly in terms of population as a result of white flight. The preservation movement was two pronged, mostly augured by new residents, usually white, but also with a current resident thread, in some African-American neighborhoods.

The preservation movement was also an outgrowth of the anti-freeway movement in places like Greenwich Village in NYC, the French Quarter in New Orleans, Washington, DC and other places. The National Historic Preservation Act was first passed in 1966, and it called for protection of designated neighborhoods vis-a-vis federal undertakings, in particular, freeway projects.

3. The "Community Development" refashioning of the urban renewal philosophy. Community Development Corporations were created to step in and act where the market refused. And especially after the period of urban unrest (riots, rebellion, civil disturbances--choose your term) peaking after the assasination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., cities emptied out of both middle and upper income residents, as well as businesses, especially in those areas scarred by unrest.

Most CDCs built housing. For the most part, CDCs saw the solution to the urban problem in terms of the automobile-centric suburban development paradigm, and most projects aggressively suburbanized the city through the construction of strip shopping centers, shopping malls, and housing oriented to the car, driveways and parking, rather than attached, more dense housing (for the most part). Rather than enhancing population through adding residents, many CDC and post-riot renewal projects ended up reducing the number of middle income residents, and focused on serving lower-income residents.

In my opinion, in most places, the millions of dollars invested in CDCs from the mid-1970s to today have had little impact in terms of positive urban revitalization, because they adopted a paradigm antithetical to the competitive advantages of the city. I don't think they were mendacious, but I bet it's the rare CDC director or board member who has ever read Jane Jacobs.

4. Continued in-migration by people attracted to urban living, in part due to overt or covert strictures on choice or appeal of where to live. (I need better language for this.) Immigrants, artists, and other people with alternative lifestyles found urban living to be affordable and/or attractive for a variety of reasons, and continued to move into urban areas, despite recent experiences with civil unrest, national and regional trends and polices that continued to favor suburban development (including federal mortgage policies), increased municipal dysfunction and decline in the provision of services.

These populations built on the efforts started by the preservationists. In certain places with extremely low real estate demand, immigrants had tremendous impact. Improvement cumulated over generations, as financial capacity developed with assimilation and the achievement of critical mass, assisted by continued immigration by members of the extended family.

5. Renewed interest in urban living by younger and older people. Spurred in part by tv shows such as Friends and Seinfeld, as well as a desire for a lifestyle not centered upon the automobile. Some say there is actually a "bookend" effect with seniors attracted to city living as well because of the ability to get around without a car (driving abilities often degrade with age), transit, and the amenities.

One aspect of this phase is an interest in historic residential building stock is paired with demand for lower-maintenance living in multiunit apartment and condominium buildings. But a big part of the attraction are walkable neighborhoods anchored by commercial districts, cafes, coffee shops, etc.

There are many more issues that could be discussed, but then this would become a 10,000 word essay. Displacement, programs to support housing options for those of lesser means, strengthening independent retail, transit, dealing with new residents possessing a suburban, car-centric paradigm about land use, how to add infill housing and commercial development in ways that don't overwhelm extant neighborhoods, the quality of municipal services, especially public safety, and public education, the issue of change in power relations and contested spaces, are just a few that come to mind.

But one concern that initiated this piece to begin with is the failure of many new residents to understand that they wouldn't have attractive urban neighborhoods to live in if it weren't for historic preservationists and their efforts over the many decades when people thought they were crazy for remaining committed to the city.

New residents ought to be the first to support preservation, if they want to remain in a livable city, one that faces tremendous pressures to redevelop into a more dense pattern, because of the profits that can be reaped by doing so.

But this could come at a great cost: the loss of the very characteristics that make the city livable to begin with.

Labels: housing policy, urban revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home