Urg: bad studies don't push the discourse or policy forward | biking in low income communities (in DC) edition

themail, a local e-letter on good government, has sadly degenerated into an oldster policy promotion screed, including the regular denigration of sustainable transportation.

So it's not a surprise that the latest issue touts a City Lab/Atlantic Cities article, "How Low-Income Commuters View Cycling: Three policy lessons for cities trying to achieve more transport equity," that concludes that low income residents, in particular African-American residents in DC's Wards 7 and 8, aren't inclined to cycle for transportation.

The three lessons from the "study":

First, we advocate gradual policy changes in the short-term. Substantial infrastructure investments like protected lanes and cycle tracks are important, and may even increase cycling rates in the long run, but they probably do less for people who are currently uninterested in cycling and disproportionately pressed for time. A focus on making multimodal transit easier without substantially increasing time or cost—offering bike space inside subway cars, for instance, or creating secure bike parking at bus stops—might have more immediate success.In my opinion the article isn't particularly scintillating, although I am glad to see the reiteration of the need to focus on "socio-cultural shifts" or what we might call the mobility system components that support cycling.

Second, excessively denigrating automobiles might hinder cycling adoption and even poverty reduction goals. Yes, there are many ecological and social costs to car-dependent transport. But poor people face enormous multimodal challenges that should be considered in conjunction with such concerns. The rationale that leads some poor people not to desire a car-free lifestyle is likely very different from the rationale of planners and advocates who do. Cars have long symbolized social success and represented greater socio-economic freedom; indeed, some research suggests cars provide economic opportunities for low-income families. Reducing reliance on cars remains important for transportation systems, but we must also seriously consider the expressed desires of the most vulnerable members.

Finally, transportation policy must support a socio-cultural shift towards bicycling.

When "expressed desires" are counter to the policy needs of a city as opposed to the suburbs or other land use context, they should not be supported. This is the point I make all the time about "optimality vs. choice" ("Sustainable transportation is not about expanding choice, but about optimality, and how to design it into the land use and transportation system").

As the classic rejoinder from our parents with regard to peer pressure says "if your friend tells you to jump off a bridge, should you do it?" People's suboptimal transportation choices shouldn't be privileged by public policy.

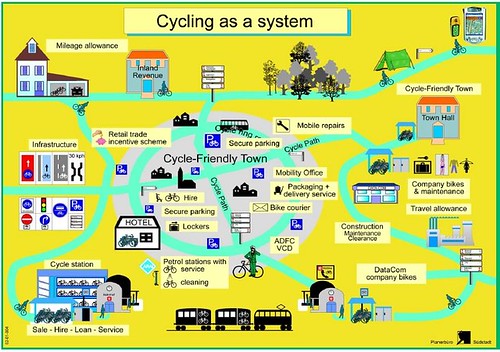

Bicycle Traffic as a system, diagram, German National Bicycle Plan, 2002-2012

My response

There is nothing new in this article concerning "low income commuters and cycling."

Like any system of mobility, people have to be trained to use it. We take that training for granted as it relates to automobility.

But the reality is that it took a long time to create a complete automobility system--including a variety of types of roads, a system to supply gasoline, gasoline stations, repair garages, places to park at various stages of trips, restaurants and motels to support people on their trips, maps, etc.

We are no where near having as complete a system to support bicycling transportation.

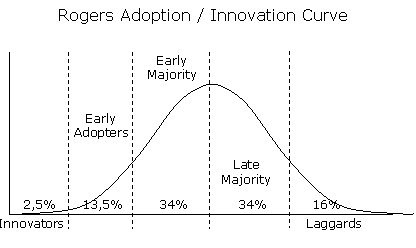

Another way to think about this is in terms of innovation diffusion theory as outlined by Everett Rogers. At best, bicycling uptake is still considered to be in the "early adopter" phase as it relates to widespread use. Economic "laggards" typically are not at the forefront of the adoption of new technologies and social change.

Lower income residents typically need more assistance, not less, in order to adopt new behaviors and "technologies" especially when the use of such equipment involves spending money. For the most part, such assistance isn't provided, so low uptake should not be a surprise.

c

cUsing ad hoc methods, it is almost impossible to counter decades of promotion of automobile primacy as the dominant mode for getting aroundtravel in the US, for either work or non-work trips.

For a variety of reasons, low income residents and African-Americans more generally lag "back to the city" trends, which include cycling and sustainable transportation promotion (e.g., look at resident opposition to streetcars as expressed by Anacostia residents as another example).

In our region, this point is demonstrated by continued African-American outmigration from Washington DC to Prince Georges County primarily and Charles County secondarily.

In conversations with various people on this issue, trying to figure out why this is, I have come to the conclusion that many later generation "Washingtonians" see "the city" as "old and tired" and the suburbs as the culmination of the American Dream even though a variety of counter-trends and perceptions exist.

This is particularly pronounced in my area of Ward 4, historically the center of the city's black middle class, where younger residents see our neighborhood as where their relatives live/d and old and undesirable. Meanwhile, virtually every house turnover brings new white or Hispanic or mixed-race couples to the neighborhood, which is changing the demographics of the ward in significant ways.

Not having read the report, just the article, it isn't clear to me that either or both a substantive literature review or a best practice review was conducted. These blog entries are a decent review of best practice in terms of barriers to cycling:

-- Ideas for making cycling irresistible in DC

-- Best practice suburban bicycle planning

-- Best (or at least better practices bike parking and bicycle facilities

-- What should a US national bike strategy plan look like?

A high quality research study would have addressed:

(1) identification of significant "barriers to cycling" including topography that make biking from "east of the river" to the core of the city particularly difficult and

(2) solutions that can successfully address identified barriers to cycling, based on a survey of best practice initiatives such as in Boston or Portland, Oregon (Community Cycling Center of Portland's low income commuter assistance program, etc.) which provide bicycles to low income commuters or residents, and provide the training and assistance necessary to adopt new behaviors.

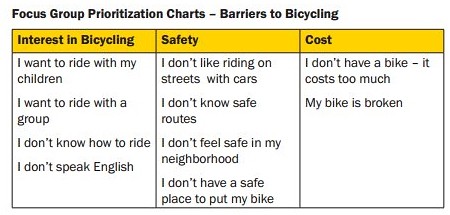

The Community Cycling Center of Portland did a study on "barriers to cycling" amongst low income populations. Unfortunately, they didn't include "cultural barriers to cycling" in this graphic.

The UK is also a great source for studies on promoting cycling uptake in diverse communities. Here are some particular best practice programs that come to mind:

- Understanding Barriers to Bicycling Project, Final Report, Community Cycling Center of Portland

- Create a Commuter program, Community Cycling Center of Portland

- Roll it Forward program, City of Boston

- Hubway discounted memberships program, City of Boston

- Recycle a Bicycle youth program, New York City

- Youth Bicycle Summit, sponsored by Recycle a Bicycle, New York City

- Neighborhood Bicycle Works, Philadelphia

- Major Taylor Bicycle Club, Seattle (Young people find cycling gets the wheels turning," Seattle Times))

- Phoenix Bikes, Arlington County, Virginia

- Bicycle User Groups Network, City of Toronto

- Community Cycling Fund for London, London Cycling Campaign

- Momentum Bike Clubs, Building Dreams Initiative, Institute on Family and Neighborhood Life, Clemson University, South Carolina

- biking expos (many examples, including a women's bike expo by City of Boston and a general biking expo by the Utah Transit Authority)

Another best practice would be to systematically train all of the elementary school students in schools east of the river in safe cycling. And, there are many other best practices examples with regard to women, immigrant populations, and the disabled.

To my knowledge none of say the top 5-10 best practices that are "top of mind" for me have been implemented in a systematic fashion East of the River in DC (other than "Black Women Bike," a program created by Ward 7 resident Veronica Davis)..

But with regard to cycling specifically, while WABA has been doing trainings, and Veronica Davis created the "Black Women Bike" group, there isn't a bicycle shop east of the river in DC.

There aren't any nonprofit initiatives fostering cycling based there to my knowledge, such as bike co-ops, even though programs located elsewhere in the city do operate there.

The DPR recreation centers aren't utilized systemically as a way to foster bicycle usage.

And there are many many tough hills--e.g., try riding to the Anacostia Community Museum some time or up Stanton Road to Congress Heights, or up Martin Luther King Avenue to St. Elizabeths, not to mention limited ways to get across the Anacostia River--although the new 11th Street "local" bridge is a far better means of doing so compared to what existed previously. Etc.

Conclusion. We understand already that there are barriers to cycling take up in the US.

Comparatively speaking, bicycling take up is low for all demographic segments, regardless of income, but even lower for most lower income segments (with some exceptions, like Hispanics, see "Spelling out bike safety, in Spanish" from the New York Times).

These barriers are not unique to low income populations, but lower income households likely need additional programmatic support to assist the adoption of bicycling as a regularized mode of transportation.

What we need are focused policy solutions to move change forward.

Because most people are

Because to me the solutions are obvious, I find this very frustrating.

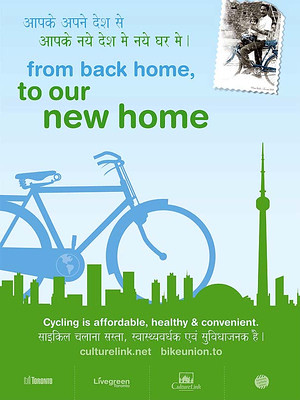

Bicycle promotion poster targeting immigrants, Toronto. (See "A Toronto program uses two wheels to connect newcomers to the city," Canadian Immigrant.)

Labels: bicycle and pedestrian planning, bicycling, car culture and automobility, change-innovation-transformation, low income households, social change, sustainable transportation, transportation planning

6 Comments:

You're assuming that "sustainable" and "cycling" belong together. They don't.

Cycling makes sense when it moves you quicker. And being a "cycle" that really means you, not a passenger.

Whether it is a social justice issue is another question altogether.

In fact, the opposite approach (build shiny new toys for the middle class first) is better suited for success. I don't see complaining "Oh, Uber isn't for poor people" or "We don't have Teslas for poor people".

(BTW, you can lease an electric smartcar for 129)

And that goes to the report, which is the car-bike cultural wars are pretty meaningless. Well except for bloggers.

Most people want a car, and most people would prefer to drive less.

Given that W4 is a bunch of old people, and the geography of W7+8, I don't see much change here. I know my biking increased by many 25% after moving to DC vs Rosslyn because of the bridge and the hill.

Three stories:

1. Got caught in a bike traffic jam of 10+ people waiting for lights on the 15th st bikelane. That is great.

2. I was riding behind a dad with a kid, and the number of dumb, agressive moves by people behind us was stagggering.

3. I almost got run off the R st bikeland into a bad street cut by another biker.

Mote in the eye, and all that.

1. whoah on the stories.

2. the basic point about biking (and walking and transit) is that the L'Enfant City optimizes those types of trips.

Plus the city wasn't built to be able to accommodate cars for every adult, on either the traffic lanes or in the various plaes those need to be parked.

3. relating to social justice, biking in the places where it is an efficient choice not only gets you there, often faster, but most importantly cheaper than the other modes.

That matters a lot when you make less money. Paying for a car is a significant chunk of household income. So if you don't have to pay for one, you can spend money on other things. It's one way to build financial security amongst lower income households.

The reality is though that it is a distance from from east of the river to downtown, etc., it's about 4 miles from THEARC to Eastern Market Metro, and further to other places. It's about 3 miles from Hillcrest to Capitol Hill.

I don't mind riding those kinds of distances (add another 3 say to get to your final destination) but most people do. Unless they are what we might call bike-dependent.

4. I better not tell Suzanne about how cheap it is to lease an electric smart car...

I have, but haven't yet read Zach Furness' _One Less Car_ which is about the identity and culture war issues.

I agree that the war is not very useful. However, understanding that the "war" is really about privilege and the use of space and the unwillingness to cede motor vehicle primacy.

"...biking in the places where it is an efficient choice not only gets you there, often faster, but most importantly cheaper than the other modes..."

hm-m-m-m...cheaper than walking, say?

RL, I'm sure this will sound harsh, but I think you have blinders on regarding the effect cyclists have on pedestrians, e.g. your comment rejiggered to express my position as a walker, specifically in my own neighborhood (where I am subjected to numerous incidents biker craziness on a daily basis), and, more generally, throughout DC and environs.

"However, understanding that the 'war' is really about privilege and the use of SIDEWALK space and the unwillingness to cede BIKE primacy ON THEM."

There is a reason that they're called "SIDEWALKS" not "SIDEBIKES" or "SIDECARS." They are for walking. There is no vehicle--bike, car or otherwise--indicated. If a cyclist wants to dismount from the vehicle/bike and walk it while he or she is on a sidewalk, that would be acceptable. Otherwise, get off the sidewalks.

-EE

not cheaper than walking but definitely faster.

and a point I should have made in response to charlie is that maybe it doesn't make sense east of the river to ride west of the river, but if you can get to and from Metrorail stations by bike that gives you a lot more control over your time and saves plenty of it. Bus service doesn't have the same level of predictability.

But yes, you don't have to convince me that sidewalks are for WALKING not bicycling.

FWIW, while I do ride on the sidewalk at times, I try to never ride faster than walking pace (unless there are no pedestrians present) and I always defer to pedestrians.

If bicyclists ride on sidewalks, then they should be trained to ride in this way.

I don't have any problems with the current restrictions on sidewalk bicycling and have no problem with those restrictions being expanded to neighborhood commercial districts and other pedestrian predominated areas.

As a pedestrian there are plenty of times I've been buzzed by bicyclists, and I hate it.

Thank you for providing such a valuable information and thanks for sharing this matter.

Post a Comment

<< Home