National Engineers Week, founded by the National Society of Professional Engineers in 1951, starts today and lasts through February 27th. There are many professional engineering organizations that address transportation engineering matters.

Two of the most prominent are the Institute for Transportation Engineers, "famous" for their manual on recommended parking requirements in association with new development, and the American Society of Civil Engineers, which publishes an annual report card on the quality of the nation's infrastructure.

-- American Infrastructure Report Card | Society of Civil Engineers

-- InfrastructureUSA

-- State by state reports, American Infrastructure Report Card

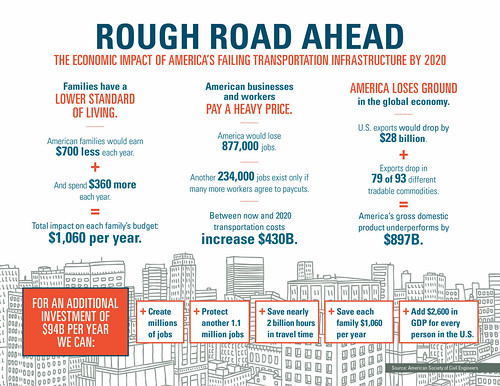

ASCE infographic.

Mostly people think about traffic engineering in terms of traffic signal timing and what they perceive are significant delays ("To Fight Gridlock, Los Angeles Synchronizes Every Red Light," New York Times).

National Engineers Week should be seized by the sustainable mobility profession as an opportunity to present engineering-related information and concepts from civil and traffic engineering that support sustainable mobility.

The need to integrate placemaking into roadway projects. In transportation agencies, the Chief Engineer is responsible for overseeing both construction and traffic engineering, but agencies tend to not be too focused on the experiential elements of the finished "product" and how it fits in within the built environment in terms of urban design and placemaking.

In response, the "Complete Streets" approach has been developed, but I don't think it's enough, because Complete Places are more than streets. Complete Streets tend to be infrastructure heavy and can stint on placemaking qualities. See the past blog entry, "Complete Places are more than Complete Streets" as well as the somewhat out-of-date Smart Transportation Guidebook for more discussion of this point.

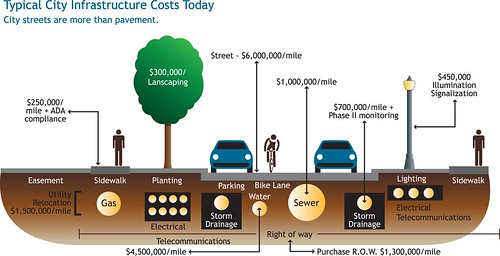

Diagram from the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Create a high-level position in transportation agencies focused on enhancing the placemaking elements of transportation projects. One of my recommendations for addressing this is for Departments of Transportation to appoint a "Chief Thoroughfare Architect" focused on the experiential quality of the constructed environment.

One way to think of this is how parks planner David Barth suggests that streets should be treated as linear parks. In any case, likely there aren't enough landscape architects working for transportation agencies. Also see "DC's bad urban design as it relates to new transportation infrastructure" and "I think this is hideous: metal sculpture on the New York Avenue bridge."

St. Louis pedestrian crosswalk painted in leaves to call attention to its location by the Missouri Botanical Gardens. Photo by Robert Cohen, St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

In the past couple weeks, media attention has been brought to the experiential quality of streets when St. Louis traffic engineers, relying on guidance from the Federal Highway Administration, stopped supporting the creation of artistic treatments within pedestrian crosswalks ("St. Louis will let crosswalk art that violates federal rules fade." St. Louis Post-Dispatch).

Another way to address this is by calling attention to the concept of "Levels of Quality" balancing the needs of all road users rather than the "Levels of Service" method derived from the Highway Capacity Manual (link to an older edition), which focuses on speeding up the movement of traffic.

-- Level of Quality posters demonstrating LOQ concepts for biking, street elements, street crossing, transit stations, traffic calming, and walking, produced by Dan Burden of Walkable Communities.

Changing roadway materials. For example, because current practices in roadway construction create streets capable of supporting high speeds by motor vehicle traffic regardless of land use context, I argue that we should construct roadways with materials that support desired traffic speeds congruent with land use context.

One way to do so is to bring back belgian block materials treatments in cities--although it does cost more--in places that are likely to have a great deal of pedestrian and bicycle traffic, including commercial districts, and around schools, parks, libraries, and other civic assets.

Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia is an example of such a street, where the pavement provides visual, aural, and physical cues to drive more slowly.

Belgian block remains the primary pavement type on a section of South Carolina Avenue SE in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, DC.

Bridge design and incorporating pedestrian and bicycle access. Serving on the Design Oversight Committee for the 11th Street Bridge Project made me think more about treating bridge design in the city as a system ("Anacostia River and considering the bridges as a unit"), rather than dealing with each bridge separately and independent.

As it relates to biking and pedestrian infrastructure, it's important to stress the integration of access for sustainable modes when bridges are constructed. Generally this is a struggle, because there aren't national standards for such integration, instead discretion is left to state transportation agencies.

Some do a good job of it, others don't, and even within states, there can be inconsistent treatment. For example, the DC area has a number of Interstate Highway bridges that incorporate bike and pedestrian crossings, while Baltimore doesn't.

Nationally, more recently a number of pedestrian-bicycle only bridges have been created, often using bridges that have become obsolete for motor vehicle traffic, for example the Walkway Over the Hudson and the High Bridge ("Pedestrian High Bridge over Harlem River to reopen," Wall Street Journal) in New York and the Walnut Street Pedestrian Bridge in Chattanooga.

Portland recently opened a bridge, Tilikum Crossing, dedicated to sustainable mobility, serving bicyclists, pedestrians, and transit--bus, streetcars and light rail, but not motor vehicles.

Europe especially has a number of recently constructed pedestrian and bike bridges of advanced design that have been integrated into waterfront revitalization programs such as the Gateshead Millennium Bridge across the River Tyne in England. These Wikipedia photos show that bridge in both the up and down positions.

And inspired by the High Line in New York City, which repurposed a former elevated freight railroad line into a linear park, garden bridges are being created in DC (Can D.C. build a $45 million park for Anacostia without pushing people out?," Washington Post and London, although the London project has been controversial ("London's garden bridge: the end of the road?," Guardian).

This infographic from the New Jersey Institute of Technology on advances in bridge engineering shows us that there is plenty of opportunity to keep things interesting in bridge engineering.

NJIT Online

No comments:

Post a Comment