LOL Quote of the Day: fuel prices have little effect on gas consumption (Letter to the editor of the New York Times)

Yesterday's New York Times has a set of letters to the editor ("Conservatives' Plan for a Carbon Tax") on the carbon tax proposal offered by a number of Republican luminaries calling themselves the Climate Leadership Council ("Carbon Tax- Not Perfect, But Good Enough," Forbes Magazine).

One, by Scott Edwards, co-director of the Food and Water Justice Program at the advocacy group, Food and Water Watch, made me laugh good and hard:

It is promising to see conservatives finally suggesting ways to protect our planet from the effects of climate change. But their proposed solution of a carbon tax is built on a false premise: that economic pressure will attach itself to fossil fuels as readily as it does to some other consumer products.It should be obvious why I laughed.

For example, their presumption ignores the fact — as documented by the Energy Information Administration and experienced by anyone who must drive regularly regardless of cost — that fuel prices have little effect on gas consumption. This is partly why a carbon tax in British Columbia in 2008 has failed to reduce carbon emissions.

Carbon tax schemes are supported by Democrats, Republicans and even oil and gas giants like Exxon Mobil because they avoid stricter environmental regulation and allow for corporate business as usual. Only reining in the extraction of fossil fuels at their source — keeping fossil fuels in the ground — will limit greenhouse gas emissions and looming climate catastrophe.

How amazing is it that under the Trump Administration, the Secretary of State is Rex Tillerson, former Chairman of ExxonMobil?

Because the U.S. is a major producer of oil ("The Petro States of America," Businessweek; The petrostate of America," Economist), its land use and transportation planning paradigm promotes the consumption of gasoline.

To facilitate this, it means keeping the cost of gasoline relatively low.

In keeping with the promotion of oil consumption, for 70+ years, US land use and transportation policy has prioritized "sprawl," the form of land use that requires an automobile to get around.

After so many decades of developing the built environment in a manner that requires a car, of course in the short term--which over the course of 70 years can be a minimum of a decade--gas price increases of a "medium" amount won't change consumption that much, because it is very difficult to change the built environment in ways that support a reduction in gasoline use.

And in fact, on an inflation-adjusted basis, gas prices are still pretty cheap--the 30 cents/gallon I remember from just before "the gas crisis" would be $1.75 today.

Even if on the margins, price rises do lead to increased transit use ("Lower Gas Prices Test Transit Ridership Models," Wall Street Journal) and a shift from larger to smaller automobiles, with improved efficiency ("better gas mileage").

These days, as gas prices have declined, the US auto industry is selling a higher proportion of SUVs and larger automobiles ("Low gas prices boost SUV and pickup sales," CNN).

On the other hand, as discussed in David Owen's book Green Metropolis and the extensive writings by Jamie Kenworthy and Peter Newman (e.g., "Australian Peter Newman: To make a sustainable city, boost rail and reduce driving," Portland Oregonian), it is possible to create a different kind of land use and transportation planning paradigm.

In some US and Canadian legacy cities, a robust transit network and high density development means that many households aren't automobile-dependent and per capita energy consumption is significantly lower than the national average.

-- "Earth Day," 2015

The inflection point on the price of gasoline between North America--Canada is also a major energy producer--and Europe came with the "Gas Crisis" of 1973, when Saudi Arabia expropriated its oil industry and raised prices.

The US did respond to the change in oil pricing by promoting energy efficiency, in many elements of the economy, including cars, but it didn't change the land use planning paradigm, nor did the Federal Government institute high excise taxes on gasoline.

So while energy efficiency has improved for cars, appliances, trucks, manufacturing, etc., overall use has risen, partly because of the rise in population, but also because of the continued dominance of an automobile-dependent land use and transportation planning paradigm.

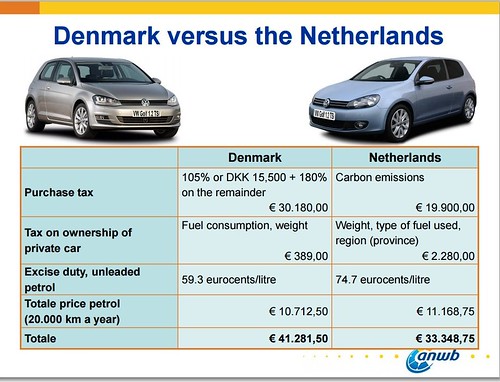

The cost to own a car both to purchase and to operate on an annual basis is significantly higher in most European countries than it is in the US. Slide from a presentation on car taxes in the Netherlands.

By comparison, in DC a 6% sales tax is applied, as well as an additional purchase excise tax of 6-8% depending on car weight, and a small registration fee. The sales and excise taxes on a car costing $50,000 would be as little as $6,000--less than 1/3 the cost compared to the Netherlands and about 20% of the cost in Denmark.

Europe is the opposite.

Out of a desire to increase their political and economic resiliency, by contrast most European countries responded to the quantum change in the price of oil by choosing to prioritize policies, practice, and investments that reduced dependence on oil.

That meant shifting to sustainable mobility when possible and to emphasize this change in policy, most of these countries significantly raised the price of gasoline, which by contrast to today's price in the U.S. of say $2.50/gallon, in Denmark, today, the price is $5.54. And such pricing has been the norm for decades.

These countries also significantly raised the excise tax on a car purchase, equal to as much as 100% of the cost of the car, and made it much more expensive and difficult to qualify for a driver's license.

In Europe, there is no question that "fuel prices have had a big effect on gas consumption."

That's why diesel engines are popular there--because they get significantly better gas mileage, but at a severe cost to air quality. It's why electric trucks are competitive with diesel engines, because the excise tax on fuel means that despite the higher cost of an electric motor, the overall cost is still cheaper. It's why transit networks in many European cities are deep and wide. It's why when people buy cars, they buy smaller ones rather than bigger ones. It's why they try to live close to work, and in denser quarters. Etc.

Is a carbon tax enough to change long term policy that prioritizes automobility? In North America, the truth is that a $40 tax per ton of carbon is probably not enough to shift the land use and transportation planning paradigm towards the kind of built environment and transportation system that isn't reliant on gasoline and the automobile.

That's why Food and Water Watch can say that British Columbia's carbon tax isn't having much effect--they are one province out of many in Canada, and policies like these need to be coordinated at a very large scale, maybe even larger than the nation--at the scale of the continent.

If you want to shift energy and land use development policy and practice, raise the price of gasoline, in steps, to levels comparable to those in Europe. Or do both. But as long as gasoline prices stay low, it is too difficult to shift behavior and practice in a structural fashion.

Instead, change comes very slowly at the household, community (many cities and counties have sustainability plans), and state/province scale, not being coordinated in a comprehensive fashion at the scale of a state, nation, or continent.

-- "Quote of the day: "it isn't the place of the government to push people out of their cars and into alternative transportation"," 2015

Labels: car culture and automobility, energy policy, gasoline excise taxes, public finance and spending, sustainable transportation, transportation infrastructure, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home