When residents of a neighborhood fight a day care center (Toronto)

When I ran for City Council in Ann Arbor in 1987, I was called to speak at a neighborhood meeting organized to fight the approval of a day care center. I couldn't bring myself to be against it, and it cost me votes although I would have lost anyway (I ran in a Republican ward, back when the election for local offices was in the Spring, disconnected from the state and national election cycle, which got students out to vote).

I sure didn't understand transportation demand management then, but the fact of the matter was that the proposed location was at the very outside edge of the neighborhood, proximate to a major street and so the traffic of dropping off and picking up children wouldn't have impacted them.

(These days I do argue that while embedding schools and such in neighborhoods is a good thing, at the same time they need to be placed in ways that facilitate traffic movement and that these kinds of facilities need to have transportation demand management plans to minimize negative traffic impacts.)

Columnist Edward Keenan of the Toronto Star writes about the Cabbagetown neighborhood's successful opposition to the approval of a day care, which didn't go through a relatively objective approval process, but through the City Council ("Consider the character of a neighbourhood that rejects a daycare")..

From the article:

I am trying to imagine the absolute misery of a life that would lead someone to say — publicly — about the sound of children playing in a backyard, that “the idea of tolerating this type of noise is frankly ludicrous, and completely incongruent with this, or any other, residential corner in this city.”

How scarred and dark the psyche of an adult human being would have to be for her to stand up in a room full of other people and suggest that strollers on a front porch present an unbearable “heritage concern” or a threat to the “character” of a neighbourhood. ...

Good neighbourhoods need day nurseries, and they need schools and healthcare facilities, and other amenities. For that matter, a strong city needs homeless shelters and needle exchanges and half-way houses. Many of those are things you might prefer to locate a few blocks away, rather than directly next door to your house. But all of them are things that need to go next to someone’s house. “I was here first and prefer not to have anything change on my street” is not an argument worthy enough to justify impoverishing your community and your city.

Given the range of possible new uses for a building—a Wal-Mart, a tire factory, an abattoir — most of us would find a new daycare welcome, even enriching. A sign of our neighbourhood’s health. ...

Indeed, it seems to me that if somehow the presence of children threatens the character of your neighbourhood, then the character of your neighbourhood sucks. And if you find yourself arguing for the preservation of that character over serving the needs of a living urban community of your neighbours, consider that you might benefit from spending some time reflecting on your own character instead.

=======

You get what you plan for

(Also see "Keeping Cities from Becoming “Child-Free Zones”: With kids on the decline in urban areas, cities can make themselves more attractive to young families by building more playgrounds," Governing Magazine.)

While I don't have children, I live in an area with children, and close to a bunch of schools, and we have watched the two girls next door grow up, and we interact with them and other kids as a result.

For a long time, the idea was that the city wasn't a place for kids, that you need a big yard which is only available in the suburbs (our neighbors as it happens do have big yards), city schools aren't very good (an issue to be sure but an overgeneralization at the same time), public safety as an issue, that commercial districts were only for adults, etc.

But it's not that simple. Or that hard. Making places amenable for families and children merely means taking the time to consider those needs, and accommodating them, like playgrounds. How hard is to have a pocket park playground in a commercial district, especially the larger ones? It's not hard at all.

And kids repurpose stuff anyway. I've seen kids play on bike racks, while I use them for parking. Play on rocks put into the streetscape, etc.

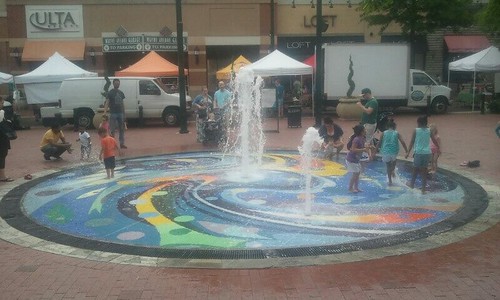

Children watching a street performer on Ellsworth Ave. in Silver Spring, Maryland

A public scrabble board set up on one of the piers at the Wharf District, Southwest DC

The charter school a couple blocks away put the playground in the front yard and it is open to the community.

A hopscotch box painted on a driveway, Maple Street, Takoma Park. Maryland

Kids playing on a kinetic sculpture in Takoma Park, Maryland

Labels: building regulation, children in the city, civic assets, commercial district revitalization planning, families and the city, integrated public realm framework, urban design/placemaking, zoning

4 Comments:

There are other things at play as well. Smaller families, rise of childlessness, changing parenting styles and greater segregation (not so much on race but age and the like). People can live in 55+ communities or try to make their communities more adults only spaces. This seems easier when there are very few kids in the community to start with.

People, citizens, seem to get irritated with city related things they don't think are for them. We see this with dog parks and bike lanes. In my native Florida, northern retirees grumbled about paying taxes for schools. Of course it does not help that the property tax bill lists how much goes to public schools.

The other thing I wanted to briefly note is helicopter parenting and others' support of that kind of parenting style. Parks may go unused if the equipment there is for elementary and middle school aged kids, if those kids can only access those parks as long as they can drag along a tired adult to watch them. And we've experienced parks that were nothing but hangouts for druggies and bums, despite the presence of playground equipment. Many parents would be unwilling to let their kids visit such parks regardless if they are accompanying them or not.

wrt the last paragraph, I will say that the Takoma playground used to be pretty crappy. We'd take the girl next door there, and normally there would be no more than a handful of people there. Then they reinvested in it, fixed it, redesigned and reequipped it so that it appeals to a wider age range, not just kids from 3 to 8.

Now hundreds of people are using it during the high use periods on the weekends.

Granted you need to make those kinds of investments where they will be used.

E.g., Fort Lincoln has an elementary school. But 90% of the housing (before the rowhouses) was set up to be senior housing. Should they be surprised there were never enough children to populate the local elementary school?

https://www.geekwire.com/2018/secret-footage-hopscotch-court-downtown-seattle-proves-lot-us-still-kids-heart

Don't have much insight into the "I'm not using X, why should I pay for it" trope. Yes, that's a problem especially with schools. And in a lot of communities it's a huge amount, e.g., in small districts in NY or NJ, people pay multiple tens of thousands of dollars in property taxes, the bulk for schools.

Yes, dog parks and bike lanes. I use bike lanes. Not dog parks. I don't use playgrounds. I begrudge none of them.

In fact, one of my criticisms of Derek Hyra's book about "investments in bike lanes" and not parks is that it was wrong. In the early part of last decade, DC spent hundreds of millions of dollars upgrading rec centers, many in lower income communities or used by low income households.

Post a Comment

<< Home