From Bloomberg: A Commuting Resolution for 2025: Ride Your Local Subway or Bus Regularly

-- article

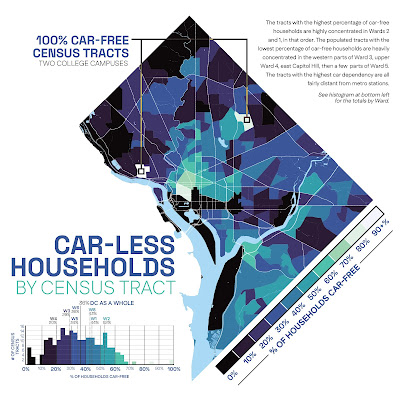

Only 3.1% of US adults use public transportation to get to work, according to 2022 data from the Census Bureau, down from 5% in 2019. That year, almost 76% of Americans said they drove alone to work, a number that fell to 68.7% in 2022 as more people reported working from home. Among those who take transit, 70% were located in one of seven metropolitan areas — Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Washington, DC.

This heavy reliance on private vehicles comes with a steep cost — both personally and to the environment (not to mention the fiscal health of your local transit agency). The average US household spends $13,174 per year on transportation, more than 85% of which go to car payments, gas and other automotive expenses. Driving costs help make transportation the second-largest expenditure for Americans after housing, representing roughly 17% of household income. In the European Union, it’s only 11%.

Transportation also accounts for 28% of US greenhouse gas emissions, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, with nearly 60% coming from cars, SUVs and pickup trucks. And while electric vehicles can help reduce that figure, research from the California Air Resources Board and others have found that switching to battery-power alone is not enough. To stave off the worst effects of climate change, fewer people need to be driving.

And yet getting more people in the US out of their cars has been difficult. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, transit ridership was falling in most US cities, with success stories such as Seattle’s expanding bus ridership standing out as a rare exception. Even nudges such as offering free fares have not substantially moved people from behind the steering wheel and onto trains, buses and light rail. A big part of that problem is structural — lots of US communities simply don’t have good enough transit service.But even in cities with bus and train networks that are adequate for commuting, many people still opt to drive. For some of them, driving to work is just a habit, and habits are hard to break. Research has found that people will only change their commuting habits “when they’re starting a new job or when they’re moving,” says Ariella Kristal, a behavioral scientist and postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University. “But they’re not just going to, in the middle of daily life, change an entrenched habit.”

Transportation Demand Management. Like with biking, people need assistance/help to make the transition from one mode to another. The US has spent the last 100 years prioritizing automobile dependence.

Labels: bicycle and pedestrian planning, car culture and automobility, transportation demand management, transportation management districts

.jpg)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home