Independent bookstores with a general stock might need to rethink their business models (revised)

Jaime of Stop, Blog & Roll has turned me on to a daily e-newsletter about the book industry and bookstores, called Shelf Awareness. Today's edition links to a Tucson Citizen story about the failure of Biblio, a pretty new store in downtown Tucson. I think that this story, "Final chapter: Downtown bookseller Biblio closing after 3-year run," (and SA has multiple stories each week about bookstore closures) communicates that bookstores have to change how they think of their market and their business plan, in order to succeed as independents.

The problem with retailing books in smaller places is that the average book, in a particular community, has a small market. (E.g., how many people want to read about commercial district revitalization even in a big city like Washington, so if I was a book buyer, and I bought only for my own tastes, I'd have a lot of stock sitting around on the shelves, unsold.)

VAL CAÑEZ/Tucson Citizen. The slow pace of downtown development didn't help Biblio's prospects, says owner Maggie Golston, but the corporatization of bookstores was the bigger reason behind her decision to close Biblio's doors. "You can't find a mom-and-pop hardware store . . . and books are the next thing to go."

VAL CAÑEZ/Tucson Citizen. The slow pace of downtown development didn't help Biblio's prospects, says owner Maggie Golston, but the corporatization of bookstores was the bigger reason behind her decision to close Biblio's doors. "You can't find a mom-and-pop hardware store . . . and books are the next thing to go."Plus, while the owner of Biblio criticizes the "corporatization" of bookselling, which because of Borders and Barnes & Noble, is increasingly competitive for the small shops, especially those that don't specialize, it really has a lot to do with the Internet, Amazon Books, and the creation of online bookbuying opportunities in many venues, from ABE Books to ebay to Powell's, etc.

Unless you are able to create a massive independent destination like Powell's in Portland or Tattered Cover in Denver, I think bookstores have to think more broadly and develop multiple revenue streams, most likely through cafes and restaurant operations, at least in smaller markets. And by smaller markets, I don't just mean cities, I mean traditional commercial districts that are in "big markets" but since most local businesses get 90% of their customers from a three mile radius, it doesn't matter that you're in "a big market" because your own retail trade area is but a piece of the big market.

It's a little different, but still not easy for specialty bookstores. Low rents and a destination clientele can make such bookstores work. Or high rents, but in the right location, such as the cookbook store in the Reading Terminal Market, can still work out. It's all about the rents and the margins and the inventory turns.

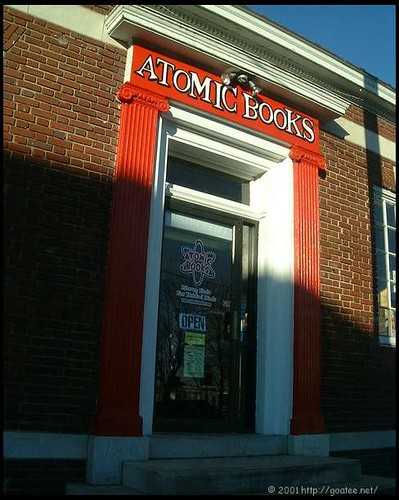

Atomic Books in Hampden Village in Baltimore is a cool place, but it has a unique appeal (zines and similar items, graphic novels) and a deep stock, and likely doesn't have to pay too much in rent. Photo by Goatee.

Atomic Books in Hampden Village in Baltimore is a cool place, but it has a unique appeal (zines and similar items, graphic novels) and a deep stock, and likely doesn't have to pay too much in rent. Photo by Goatee. Jill Ross' Cookbook Stall, from the Reading Terminal Market website.

Jill Ross' Cookbook Stall, from the Reading Terminal Market website.In the article, the owner attributed many of her difficulties to problems in revitalization of the area. I don't doubt it. Market development is tough, and emerging and transitioning commercial districts have particular difficulties. From the article:

Golston acknowledges that part of the problem that led to her decision has been the slow pace of downtown's redevelopment, not enough support from the city for downtown's smaller merchants, and little being done to solve the area's social ills and make it more inviting to Tucson shoppers.

How many times do you go into a bookstore and browse, but don't buy anything? But if you were buying food, hmm, it changes. We eat every day. But we don't buy books every day...

A University of Arizona business school professor attributes the closure of independent bookstore to changes in the industry and economies of scale enjoyed by the chain stores:

Marshall Vest, director of economic and business research at the University of Arizona's Eller College of Business said it all has to do with economics. "We are seeing consolidation in many industries, which reflects actually new and improved business models." Consolidation isn't new, but it has accelerated in recent years and you see it in banking, in retailing, in lumber yards, and in bookstores, Vest said.

Basically, the big players have become very good at what they do (selling books, for example) and they outsource the other pieces of the business, such as payroll or advertising. In the process they become very efficient, and make it very hard for small stores that don't have the size or the know-how to compete. "It's terrific for the consumer because they have a wider choice of product at a lower price," Vest said. "It's a 31-flavor world nowadays, and consumers like choices."

I think he's overly facile with his explanation. Chain stores enjoy a number of advantages compared to independent bookstores. First, chain stores usually buy books at a 50-55% discount, which adds 20% or more to their gross margins compared to independents. Second, chain stores get financial considerations not often granted to small independents. For example, when you see a big end cap at a store featuring a specific book, or books on prominent tables, a chain store is likely to be paid extra for placing books there. Third, for books bought in large quantities that don't sell well, they will be "remaindered in place" for chain stores, which mean the store gets a financial payment to keep the books, but to sell them at a steep discount. Finally, chain stores are likely to receive buildout allowances and rent considerations--terms unlikely offered to an independent bookstore.

As us Washingtonians know, Kramerbooks and Afterwords Cafe on Dupont Circle is a perfect example of combining a bookstore with a cafe to make a destination and to make more money. The restaurant is in one of the best locations in the city, enjoying access to a dense nearby residential population likely to go out at night, across the street from a subway station, and conventient and popular with business travelers and tourists. The cafe does at least $6-7 million/year in food sales. And the bookstore turns its book inventory on the average of once/month, which is about 7-8 times more in a year than the national average for bookstores.

This means less money is tied up in inventory, and more goes into the cash register. (See this article from the AU student newspaper for background. The numbers I'm using come from memory, from a Publisher's Weekly article from ten years ago or more.) Even so, the average Washingtonian probably spends more money at this place on food than on books...

According to the AU article "Kramers has been rated the nation´s highest-grossing independent bookstore per square foot within the past few years." But the neon in this photo from Furcafe also explains where they make a goodly amount of money--from wine, beer, liquor, and food...

According to the AU article "Kramers has been rated the nation´s highest-grossing independent bookstore per square foot within the past few years." But the neon in this photo from Furcafe also explains where they make a goodly amount of money--from wine, beer, liquor, and food...Note that you have to be very careful on where you try to do this. A Kramerbooks in Arlington County, with the same concept, failed. I don't know enough about that area to have tried to figure out why. I do think that any concept needs to be rigorously considered before it is duplicated willy-nilly elsewhere.

Note also that I have discussed this in the context of getting college bookstores out from the campus and onto the streets of the adjoining neighborhood, in order to make a local bookstore available and likely more successful because it could already count on the steady revenue stream from the sales of college textbooks and related sundries (how much money could Georgetown make selling college logo merchandise with a store on Wisconsin Avenue?).

See the blog entry "University + Community = Bookstore" and this press release about the opening of the Pratt Institute bookstore on a street in the Brooklyn neighborhood adjacent to the school, rather than deep within the campus.

Prattstore College Bookstore in Brooklyn. Can't say I love the design, but I do love the idea. Photo by archit_k at Wired New York.

Prattstore College Bookstore in Brooklyn. Can't say I love the design, but I do love the idea. Photo by archit_k at Wired New York. Note that the new Borders in Downtown Detroit appears to be doing pretty well, although they have the money to be able to support the long term development of new markets. Most independent business owners don't have that kind of patient capital, or multiple-revenue streams which allow certain locations to be subsidized by others. (See "New businesses give Detroit reasons to hope for the future," from the Detroit News.)

Don't get me wrong. I think making bookstores work these days is damned difficult. That's why proprietors must rethink the whole business model. Bookstores are integral parts of livable communities, but the way the economics (a small bookstore makes less per copy than the big chains, maybe about 40% of the list price of the book, and from this comes rent, salaries, other expenses, and hopefully a modicum of profit) and market works, it's a brutal business.

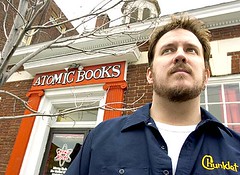

Benn Ray, owner of Atomic Books on 36th Street in Hampden, is leading an effort to prevent chain businesses from opening on the community's commercial strip. (Sun photo by Monica Lopossay). Dec 30, 2005

Benn Ray, owner of Atomic Books on 36th Street in Hampden, is leading an effort to prevent chain businesses from opening on the community's commercial strip. (Sun photo by Monica Lopossay). Dec 30, 2005Index Keywords: retail

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home