Historic preservation in low income neighborhoods

Disinvested block in Philadelphia. Flickr photo by MikeWebKist.

Disinvested block in Philadelphia. Flickr photo by MikeWebKist.On the forum-l e-list (the Preservation Forum), there has been a discussion about the creation of historic districts in "low-income" neighborhoods. Because historic preservation based revitalization strategies tend to be the only strategies that work long term (sustainable) in rebuilding cities or at the least stabilizing and improving disinvested neighborhoods, you can imagine that I am a proponent. However, it's important to look at this issue in a more micro fashion.

Below is what I wrote (slightly edited), in two emails:

In strong real estate markets, the value of historically-eligible buildings and districts is already reflected in the asking prices of houses. This is true in DC and I can't imagine it is not true in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

So it ends up being a chimera to say that historic designation will lead to displacement. Displacement, for a wide variety of reasons, is already occuring, whether there is a historic district or not. (cf. "Gentrification article in USA Today")

I have written about this issue a fair amount, in "More about Contested Space: Gentrification" -- -- "Community Preservation and Gentrification" and "Saturday musings on "gentrification," change and what, if anything, can we do about it."

[From "More about Contested Space":

As far as displacement goes, it's part of what people call "gentrification". But gentrification is phenomenon with multiple effects, which I describe as:

(1) new investment in a previously underinvested area;

(2) change and different people coming into a neighborhood -- most importantly, different people from those currently in residence (the differences--race, class, ethnicity, levels of educational attainment, attitudes toward the urban experience, etc.--are usually not "celebrated" (I make this point because I still remember first being taught about diversity and multiculturalism in 7th grade, and I specifically remember the "melting pot" and "celebration of differences" phrase -- I have a hard time seeing the celebration, at least in DC);

(3) increase in conversion of previously rented dwellings to owner-occupied, leading to a displacement of renters and an overall reduction of the number of rental units available in the neighborhood;

(4) related to the new demand for living in the neighborhood is an increase in rental rates, which contributes to the displacement of low- and moderate-income residents;

(5) neighborhood improvement as investment (primarily through the renovation and sale of houses to new residents) continues to increase and begins approaching critical mass (cf. Goetze Building Neighborhood Confidence);

(6) faux-displacement as long-time residents decide to "cash out" and take profits on the sale of the finally appreciated property (this is accelerated by, in my opinion, the still prevalent pro-suburban, anti-city attitudes embraced by particular demographics that tend to represent the long time population groups in traditional center cities); and

(7) ongoing increases in property tax assessments which contributes to the displacement of longtime residents on fixed or lower incomes (note that this effect is hard to separate out from [6]).

Note that Lance Freeman's work which finds that displacement doesn't increase with "neighborhood improvement" is explained by the fact that lower-income households want to stay in nicer neighborhoods, just like anybody else, and respond by doubling up (increasing the number of rent-payers in a household) and/or by paying more of their total household income stream in rent.]

In weak real estate markets, historic designation likely leads to increased interest of otherwise under-appreciated building stock, which likely leads to increased community interest, self-investment, efficacy, and improvement.

In strong real estate markets, the point and value of historic designation varies according to the vagaries of the local legislation. In DC, I am a strong proponent, because local laws provide strong protections limiting demolition, and for helping to maintain and strengthen architectural integrity.

Perhaps most importantly, under DC zoning regulations, only in historic districts is there a mandatory process for design review. This is pretty significant and important, and one of the most important reasons to advocate and agitate for historic designation in DC.

Someone quoted from a Philadelphia City Paper article, "What Price Preservation:"

"There's a thin line between critical revitalization and excessive gentrification. Historic preservation "can help save a crumbling neighborhood; It can alsobe used as a form of economic cleansing - a way to 'improve' a neighborhood by attrition, forcing the less affluent to sell out to those who can keep up with the expense and paperwork....

If you are approved for federal historic tax incentives, there is a 20 percent tax credit available to investors. This credit is available only for rental properties. Say the total development cost is $100,000. An investment of $20,000 for a tax credit of the same amount can lure funding from people who would not otherwise dream of an edgy neighborhood like Parkside, and make a significant dent in mortgages for those, like Brown, with equal passions for history and community."

Penrose Rowhouses, Fairmount, Philadelphia. Flickr photo by MikeWebKist.

Penrose Rowhouses, Fairmount, Philadelphia. Flickr photo by MikeWebKist.The Philly City Paper article is proof that it's important to distinguish between strong and weak real estate markets, and from an advocacy standpoint, to think about broader policies we need to push at the local and state levels.

Most traditional center cities (at least from St. Louis eastward) have thousands and thousands of vacant buildings. This is part of what defines a weak market. (Not DC, not Center City Philly, but other parts of Philly, not Brooklyn Heights, etc...)

I was in Baltimore Thursday for market research purposes and it practically makes me cry to look at block upon block of almost completely empty (eligible for designation historic) housing. Baltimore has more than 16,000 vacant rowhouses and thousands of empty lots. Detroit has 55 square miles of empty land. Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Newark, ...

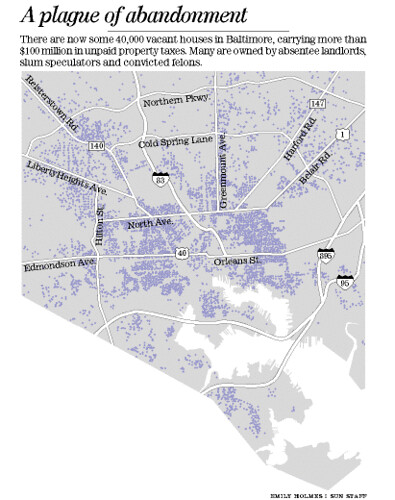

Map of vacant houses in Baltimore. Baltimore Sun graphic.

Map of vacant houses in Baltimore. Baltimore Sun graphic.The Parkside neighborhood in Philly has many vacant buildings, and so do nearby neighborhoods such as Girard Avenue. In fact, it was going on a tour of Girard (at the Urban Forum in 2003), seeing block after block of vacant buildings, and then hearing a city official talking proudly of building these godawful new dinky houses that sold for $50-60K (and appreciated to $80K) while a block off the main drag there were plenty of amazing 3-story large historic rowhouse buildings, often shells, led me to write an op-ed that ran in the Philly Daily News, comparing Philly and DC and these issues.

So it's hard for me to get worked up about potential negatives of reinvestment in weak market center city neighborhoods. For the longest time that's what I focused upon more than displacement, because mostly, I see vacant buildings coming back on line, rather than displacement.

However, I have come to agree to the use of the word "gentrification," which for me is defined as neighborhood investment and improvement that has significant market effects (on rents, demand in general, prices of houses for sale, and on property tax assessments) without any provision-protection for people of limited means. But gentrification tends to be an effect prevalent in strong market cities almost exclusively.

The blog entry that I cited before, "Community Preservation and Gentrification," discusses this in more depth. Lance Freeman's work has been used to say that preservation and neighborhood improvement doesn't lead to displacement. This has been true in NYC, in part because people spend an increasing amount of their income stream on housing. But it is also because, compared to most cities, NYC has more programs that provide a variety of housing assistance and the maintenance of housing for people on limited incomes (i.e., NYC giving or selling at low-cost buildings to housing coops, land trusts, etc., which then produce affordable housing which remains somewhat disconnected from normal market forces).

Strong markets have different dynamics. It's hard to remember though that this can change very fast. Even in 2003, you could buy houses and commercial buildings relatively cheaply in many DC neighborhoods. Not now (even though the market has cooled a bit).

Without looking at this question in a very nuanced way, it is hard to pull out meta-lessons that are helpful and shed light on multiple situations and settings.

E.g., the tax credits are written to only benefit properties with a 5 year income stream. That means rental properties when it comes to housing. If it's a building previously empty, like a warehouse or factory newly converted into housing, this is adding housing inventory and how is that bad? If it's something that works toward a conversion of rental housing to condos, maybe it's a different story.

But as we all know, only at the state and local level can there be various incentives for residential owner-occupied housing in historic districts. And some places have some interesting incentives or policies that mitigate against displacement when neighborhoods become designated (i.e., San Antonio has a 10 year property tax freeze for owners of record before the change in historic status).

I do think that designation can create hardships for those on limited income, if down the road for maintenance or other reasons, property owners must make changes that because of the architectural integrity issue, are more expensive than if the area were undesignated and they could use aluminum windows, siding, baling wire, and whatever other materials Home Depot has on sale (i.e., fanlight doors not historically accurate for the DC region) with impunity. Note that I think that maintaining and enhancing the historical integrity of a house benefits the property owner by increasing the value of their house, which likely comprises the most significant portion of their total household asset portfolio.

I think it's important for localities to develop revolving funds, tax credits, and other programs that can mitigate the hardship that architectural integrity issues can cause.

And in weak market cities, I think it's important to offer tax abatements and other programs to attract people with incomes into disinvested neighborhoods that desperately need to add economic, social, and organizational capital in order to turn around otherwise desperate situations.

Would historic preservation, bringing more attention and interest to disinvested neighborhoods, be such a bad policy for this neighborhood? Disrepair and disorder: Two of George Dangerfield's rental properties on North Regester Street: 1829 (with plywood around first-floor window) and 1831 (house next door). (Baltimore Sun photo by Kim Hairston) May 29, 2001.

Would historic preservation, bringing more attention and interest to disinvested neighborhoods, be such a bad policy for this neighborhood? Disrepair and disorder: Two of George Dangerfield's rental properties on North Regester Street: 1829 (with plywood around first-floor window) and 1831 (house next door). (Baltimore Sun photo by Kim Hairston) May 29, 2001.(I joke that the "old" "hysteric" preservationists criticized today were the "urban pioneers" of 30-40 years ago.)

Traditional center cities, for the most part, are still in desperate straits. Complaining about "gentrification" in weak market cities hardly focuses on the real and persistent problems of disinvestment. The point is to get reinvestment, and figure out a way to do this that doesn't deleteriously impact people with few protections vis-a-vis the market.

Index Keywords: historic-preservation; urban-revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home