Understanding gridlock (and extending the concepts to parking inventory)

(Text and image from Danspotting.)

(Text and image from Danspotting.)Caption: The community on the bottom is much more walkable and transit-friendly than the community on top, but for the sake of argument let’s ignore that and assume that everyone in both communities will drive for all trips. In the top community, anyone traveling from their home to work, a store, or any place that isn’t in their immediate residential “pod” must first drive on to the shared arterial highway. All traffic, regardless of where it is going or coming from, uses that same single road to get there. That road inevitably becomes hopelessly congested. Conversely, the community on the bottom is laid out in a manner that provides many different routes for any given trip. Different people could travel between the same destinations any number of different ways, and there is no need for anyone who isn’t traveling outside the area altogether to get on the arterial highway even once, if they don’t want to. No single road gets too busy because every street in the neighborhood is created equal.

Danspotting has a nice entry explaining why gridlock, or traffic congestion, works the way it does because always extant latent and induced demand can increase traffic by upwards of 40% (my interpolation, not his). One thing he didn't mention is throughput per lane of road, which I've mentioned from time to time, using figures presented by Jeff Tunlin of Nelson/Nygaard, at the DC Great Streets conference in January. It's useful to think about these numbers while considering this topic.

One lane of roadway/or equivalent can move in one hour

-- 900 cars;

-- 6,250 people by regular bus service;

-- 10,000 people by bus rapid transit; and

-- 16,000 people by light rail

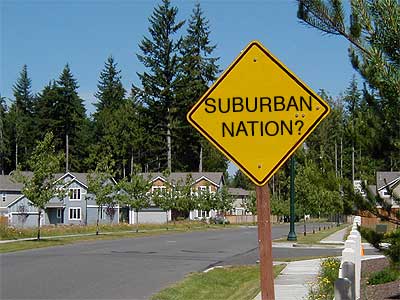

The Danspotting entry also has an extensive excerpt from Suburban Nation, which he calls, "arguably the second most influential book on urban planning." Do you agree? What would be your vote?

Image from the Suburban Nation course at Evergreen College.

Image from the Suburban Nation course at Evergreen College.Another Virginian making similar arguments as Dan, is Ed Risse, the land use commentator on the Virginia politics website entitled Bacon's Rebellion. In the entry "Dying Young in Traffic" (linked to in the entry "Urban Health, Nasty Cities, Broken Windows, and Community Efficacy") he writes:

The Private-Vehicle Mobility Myth is cited often in this column. It is one of the myths addressed in “The Myths That Blind Us,” October 20, 2003. Most recently, we explored this myth in “Clueless,” January 19, 2004, and in “Self Delusion and Fraud,” June 7, 2004.

For those who just came in, here is a refresher on the Private-Vehicle Mobility Myth:

Regardless of where they live, work, seek services and participate in leisure activities, citizens believe that it is physically possible for the government to build a roadway system that allows them to drive wherever they want to, whenever they want to go there and arrive in a timely and safe manor.

The Private-Vehicle Mobility Myth helps parents convince themselves that the house with the “big yard” may be a long way from where the jobs, services, recreation and amenities are now, but that will change. Politicians reinforce the myth by continuing to promise that “soon” they will improve the roads and the big yard owners will be able to get to wherever quickly.

There is a companion illusion that all the things the family needs for a quality life will somehow be much closer when those roads are built. It is never mentioned that the current mobility problems are the result of the scatteration (aka, random distribution) of urban land uses. It is also not acknowledged that more roads will not improve mobility and access unless there is a Fundamental Change in settlement patterns that result in the creation of Balanced Communities.

Now I haven't read Donald Shoup's book yet The High Cost of Free Parking, but I imagine the arguments are similar, about latent and induced demand, as well as street capacity. This keeps coming up in themail, the e-newsletter from DC Watch, the good government website, in the context of the churches and parking issue.

People keep using the example of Bethesda and Silver Spring building parking garages as something we need to consider for our neighborhoods in the center city.

BUT the Bethesda and Silver Spring parking garages were built in the commercial districts, for commercial purposes. So this example is completely irrelevant to the issues of residential sections of neighborhoods.

Tear these houses down for a parking structure. Caption: Rowhouses on 8th Street NE (by Gallaudet University), Washington DC. Photo by Inked78.

Tear these houses down for a parking structure. Caption: Rowhouses on 8th Street NE (by Gallaudet University), Washington DC. Photo by Inked78.Besides creating physical blight in what are normally beautiful neighborhoods, a system of neighborhood parking structures would do at least five very very dumb things:

(1) replace houses with parking garages;

(2) which would reduce property tax revenue;

(3) and would also reduce income-tax revenue, because there would be fewer residents;

(4) to accommodate the perceived needs of mostly suburban church goers, for Sunday parking, for maybe 3 hours out of a 168 hour week; and

(5) would induce car purchasing by other city residents because they would have more places to park, therefore a greater willingness to own cars, which would crowd the streets, adding congestion.

With regard to the latter point, it is true that the gridded street pattern that defines Washington provides many different ways to spread out vehicle load, as pointed out by Danspotting as well as in the #1 influential book on urban planning, Jane Jacobs The Death and Life of Great American Cities, but the problem is at the choke points, where capacity is reached quickly, and traffic congestion cascades.

One example would be the part of 6th Street NE between Stanton Park-Massachusetts Avenue and even up to A Street NE (with Constitution Avenue in the middle). During rush periods this area backs up for a few blocks, because only a few cars at a time can make the light at 6th and Massachusetts. Another example is H and 6th Streets NE, where the traffic to cross H Street backs up past G Street during peak periods. Etc.

Typical parking structure, one that looks pretty similar to the Bethesda and Silver Spring structures people are touting as examples for DC.

Typical parking structure, one that looks pretty similar to the Bethesda and Silver Spring structures people are touting as examples for DC.Index keywords: mobility

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home