Too often architecture is not about making great places

The header of this blog starts out with this line:

A community’s physical form, rather than its land uses, is its most intrinsic and enduring characteristic.

Which is taken from the publication Getting To Smart Growth 2.

For me this is the crux of all planning and land use matters--the built environment that results from tens of thousands of individually distinct projects and decisions and how we live, work, play, learn, and exist within that environment.

An architect-friend said recently that "most architects are frustrated sculptors." Sculptors make cool things, but not necessarily great buildings. At least in terms of buildings that are used and revered by real people doing real things.

Earlier in the week, I was in a meeting and kind of amazed that two prominent local architect-advocates didn't seem to understand the difference between "urban design" and architecture. (Of course, my opinion might be biased.)

Part of the problem is that there is no one commonly accepted definition of urban design. Doing a google search on urban design yields four different definitions. I have taken the liberty of combining pieces from two of the definitions:

The art of making places. It involves the design of buildings, groups of buildings, spaces and landscapes, in villages, towns and cities, [to] create a desirable environment in which to live, work and play

into something workable.

And Fred Kent of the Project for Public Spaces doesn't even like the term, because he feels that it focuses on design, which too often takes its focus away from people. Instead, Fred uses the term placemaking. To PPS, placemaking is about "turnimg public spaces into vital community places."

Because I think the design skills are important, I use the keyword urban-design-placemaking to refer to such matters.

For me, more than anything, urban design is about life on the street, and at the base, relies on Jane Jacobs principles about small blocks and mixed use, combined with Cy Paumier's, author of Creating the Vibrant City Center, explanation of why the cores of cities developed in the manner in which they did.

Concentration and Intensity of Use: "The intensity of development in the traditional central area was relatively high due to the value of the land. Maximizing site coverage meant building close to the street, which created a strong sense of spatial enclosure. Although city center development was dense, construction practices limited building height and preserved a human scale. The consistency in building height and massing reinforced the pedestrian scale of streets, as well as the city center's architectural harmony and visual coherence." (p. 11)

Organizing Structure: "A grid street system, involving the simplest approach to surveying, subdividing, and selling land, created a well-defined, organized, and understandable spatial structure for the cities' architecture and overall development. Because the street provided the main access to the consumer market, competition for street frontage was keen. Development parcels were normally much deeper than they were wide, creating a pattern of relatively narrow building fronts that provided variety and articulation in each block and continuous activity on the street." (p. 12)

There are maybe three levels of urban design:

1. The street level; which varies according to

2. The type of the district (residential, commercial, industrial, mixed use, other);

3. And the density of the district.

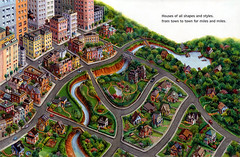

The illustration on this children's book cover is one of the most succinct explications. Urban design will vary according to the intensity and density of development, but certain aspects work the same regardless.

Illustration from cover of The House Book by Keith DuQuette.

Illustration from cover of The House Book by Keith DuQuette.One good example is the 600 block of Pennsylvania Avenue S.E. With only a couple exceptions, the storefronts on this block are excellent. Nicely done windowns, with storefronts not much wider than 30 feet, with traditional historic commercial architecture lines. (I need to take some photos of the block.)

But the block is about 600 feet wide, twice the size of a normal block. Jacobs diagrams why long blocks make it difficult to have a lively environment. And this block proves it. As great as the design is, other pieces don't work, and as a result, the retail experience is pretty middling, there are frequent business failures, and the mix over skews to business services.

(This is why I am advocating for mid-block signalized crosswalks for commercial districts with such blocks--H Street NE and Pennsylvania Avenue SE are prime candidates. The 1300 block of F Street NW already has such a crosswalk. But DDOT doesn't seem to be too eager to expand the practice.)

Similarly, if you want lively residential streets, you need smaller blocks, a grid system, houses set fairly close to the street, no curb cuts, etc.

Anyway, I bring this up not only because DC is engaging in an effort to create an handbook on urban design, according to this article, "Planning Office creating guide for D.C. development," from the Examiner, but also because poor New Orleans is getting hosed by starchitects taking advantage of New Orleans' post-Katrina apocolyptic planning environment to step in, with hype and theory to remake areas in their artistic vision, a vision which too rarely has little to do with people and how buildings are to be used.

See "Reinventing the Crescent" from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, about how "Five teams of architects and planners have been chosen as finalists to transform a stretch of land along the riverfront." The paper's art critic has done two follow up stories, one on Andres Duany, "The visionaries," and another about Daniel Liebeskind, "World class architect."

Also, this take on the revitalization planning process in New Orleans, which sounds different from what I am hearing from various residents involved in the process, "New Orleans Planning Update: The Unified New Orleans Plan (UNOP)" from Planetizen.

Index Keywords: urban-design-placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home