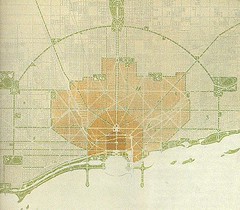

Chicago Plan from 1909

Celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Paul Goldberger, architecture critic for the New Yorker, has a succinct, interesting piece, "Toddlin’ Town: Daniel Burnham’s great Chicago Plan turns one hundred."

From the article:

Most important of all, a hundred years ago, in 1909, Burnham completed work on a document with the unassuming title “Plan of Chicago” that remains the most effective example of large-scale urban planning America has ever seen. Assisted by the young city planner Edward H. Bennett, he laid out the shorefront of Lake Michigan, quadrupling the amount of parkland and thus insuring that the lakefront would forever be public open space. He created the Magnificent Mile, the double-decker roadway of Wacker Drive, and the recreational Navy Pier, which extends into Lake Michigan. Envisioning Chicago as the anchor of an enormous region, he drafted a rough outline of highways to connect the city to the places around it. Quite simply, Burnham determined the shape of modern Chicago.

The article discloses that while Burnham has been criticized for not caring about housing for the less well off, it turns out that a draft of the plan did address such issues:

The architectural historian Kristen Schaffer, while preparing an introduction for a recent reprint of Burnham’s plan, looked at an early draft and discovered that Burnham had some surprisingly radical social notions. He called for day-care centers, police stations in which all police activities would be open and visible to the public, and improved housing for the poor, “in common justice to men and women so degraded by long life in the slums that they have lost all power of caring for themselves.” For Schaffer, Burnham’s draft indicates a belief that cities were not only “for the capitalist, but for those who found themselves in police custody or those too poor to support their children.” It’s a pity that more of these amenities weren’t built, but even the parts of the plan that were convey Burnham’s public-spiritedness. Far from being forbidding, places like North Michigan Avenue and Navy Pier are usually teeming with people. Burnham’s belief in the public realm was so powerful that it transcended all else, and it remains convincing.

Labels: land use planning, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home