Transit and community

From time to time the blog has discussed transit and the behavior of people on transit, whether or not they talk to others. Anthropologically, I would argue this is a phenomenon of regularity. On a bus, or even on a railroad commuter train, the same people tend to ride around the same time (because trains and buses run at certain times, and then with regard to the train, people tend to sit in the same cars in the same places so you become familiar with the people around you), so you become more familiar with at least some of the people and you're more likely to acknowledge them, talk with them, etc.

This doesn't tend to happen on the subway because more people ride and more people mix from multiple origin points.

So I am not sure what to make of the Discovery Channel story, "Public Transportation Passengers Avoid Getting Social," which is based on research in New Zealand, which found that:

Fifty percent of respondents said they intentionally engage in isolating activities, such as listening to music or reading, to discourage conversation. The study concluded that side-by-side seating arrangements and standoffish behaviors create a socially uncomfortable environment akin to a crowded elevator.

To change this, the researcher recommends changes in design and how seats are laid out, to foster the kind of interaction that William Whyte would have called "triangulation" (Anne Lusk, a researcher at Harvard's School of Public Health, whose dissertation is on multiuser trails, calls this a "social bridge").

----------------

William Whyte called triangulation the process by where "some external stimulus provides a linkage between people and prompts strangers to talk to other strangers as if they knew each other." (p. 154, The City).

From "Design Guidelines for Greenways," from the concluding chapter of Dr. Anne Lusk's dissertation titled "Guidelines for Greenways: Determining the Distance to, Features of, and Human Needs Met by Destinations on Multi-Use Corridors." University of Michigan.):

Except for a minimal number of elements, the environment does not facilitate interaction between strangers. While someone could hold open a door and a person passing through could say thank you, necessary ADA regulations are making many doors automatic. If social capital is to be increased and interaction between people who know one another and people who do not know one another improved, environments that might foster positive interaction should be built. At the destinations, social bridge elements could be incorporated in the built environment. These social bridge elements include four types: 1) Assist, 2) Connect, 3) Observe, and 4) In Absentia.

---------------

From the Discovery Channel article:

Thomas thinks that fostering a friendlier atmosphere would improve the ride experience and attract more public transit customers. "I think the key thing is that it's important to get a balance, looking at improvements for the social and privacy needs of the users, neither of which are being met under current design," Thomas said.

For instance, Thomas recommends altering seats to face each other since riders are 30 percent more likely to converse at that distance. Passengers also respond well to L-shaped seating, arm rests and small tables that establish more interpersonal distance.

While some transit systems have replaced awkward three-person benches with two-person or single seating, social dynamics are often overlooked in favor of maximizing rider capacity.

Of course, these suggestions are completely divorced from the requirements of "mass" transit, where you have to move a lot of people in a short period of time with limited budgets.

Auckland, New Zealand is a city of about 450,000 people in a region of 1.3 million residents. Maybe they could make buses up more like RVs and meet throughput needs, I don't know.

But a reason I find this interesting is in how the arguments of Bill Lind, co-author of the book Conservatives and Public Transportation, were represented by someone who attended a presentation of his a couple years ago. He also spoke last week at a meeting of Montgomery County's erstwhile transit advocates, Action Committee for Transit (note they have redesigned their website).

On an e-list, Martin D. wrote:

Probably the biggest difficulty for me were his notions on the inevitability of class and the need to build both cities and services that favor isolation of classes. This is a simplistic paraphrase and likely does not do full justice to Bill or his point. He's better at presenting his case and it's available in the book.

That thread started with examples from the train ride and he made the case that there should be fully separate classes on the train so that people of finer social manner would not have to tolerate the slobs in coach (including interaction in the diner.) Of course he then chose to tolerate the noisy urbanists in the private car, but private rail cars do align with his views.

While I may sympathize with this emotionally (and bitch and moan about all the crimes we have to tolerate in these days of twittering boneheads in elevators and beggars on every street corner) it's counter to my particular world view.

Bill did offer a litany of opinions and examples about ways that the constant intermixing of class (and related social, economic and philosophical behavior) was (variously) dumbing down, cluttering, vandalizing, dismantling and, at least, misunderstanding the higher potential for civilization.

So according to Martin, Lind believes conservatives will only accept transit if they can ride in their own buses and train cars.... not exactly, but he believes there should be multiple tiers of service, from better to worse, so that those who can afford better service can pay for it, and not have to mix it up with their social and economic inferiors. (my words not his)

It's not a very democratic-civically engaged type of view. And by separating users, I think you make it easier to provide less adequate service to the people who are typically less connected and engaged in the democratic process.

In the "old days" into the 1960s for sure, in cities at least, it was typical to ride transit to work and leave your car (if you had one) at home. That was aided by relatively short distances between home and work, and the concentration of major office centers into relatively few places.

As worksites and residences dispersed widely, from the standpoint of efficiency, these places became disconnected and less able to be effectively served by transit. So people started driving to work.

As Mr. Lind's "betters" stopped using transit, they also became disconnected from caring about the quality of transit service, because they believed that people should drive and that transportation priorities should be focused on creating, maintaining and extending a robust road network to facilitate automobile (and truck) travel.

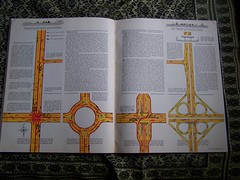

Spread on ideal highway construction, Fortune Magazine, August 1936.

There is a good deal of that in the Washington region today. Because of the existence of both heavy rail (subway) -- with both metropolitan commuter and local service aspects, complemented by long haul motor coach commuter bus services, and mostly local bus services, there are two tiers of quality in the provision of transit service in the metropolitan area.

In the center city, where if you have the right timing and location, bus service can be just as efficient as subway service, most "choice riders" (meaning people who have the choice of using transit or not, vs. transit dependent riders who have to use what is provided, or they won't be able to get around at all) ride the subway.

The Washington Post published this graphic as part of a big piece about bus transit in 2005. (See "Agustin (and many others) have a hard time hopping on the bus" for the link to the story.) Clearly, you can see that subway riders generally are much higher income than bus riders, and have more cars/household.

WMATA has been upgrading the bus fleet to make the service better. But their ad campaign on the improvements has been misfocused away from this, and towards how the bus can also get people to various places in the region. The Examiner got around to writing a story about this a couple days ago, "Metro spending $739000 to tout flagging bus service," but I wrote about it in late November, "What's wrong with this Metrobus ad?."

But bus service can still be very inconsistent. And as long as people with organizational, social, and civic capacity don't ride transit, or specifically buses, they aren't going to be there, advocating for improvements and demanding that the service continue to be provided.

In short, there is a long way between Lind's "separate but equal" ideas and Thomas' "let's make buses up like cocktail lounges" ideas, but there is no question that without people of various classes mixing on transit, we will continue to have substandard transit offerings.

This is very much apparent in areas where rail options don't exist. Then, only the people who are transit-dependent are transit riders.

Labels: capacity building, civic engagement, participatory democracy and empowered participation, transit marketing, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home