Demolition, demolition by neglect, and the need for better laws and processes in DC

I got roped into a email-chain on the topic, where it was expressed that why couldn't the big bad Capitol Hill Restoration Society, "known for its terrorizing of good folk who want to do stuff to their houses" (mostly an overstatement but that's another issue) couldn't do anything, are they just like the Big Bad Wolf, focusing on the little issues and missing the big picture?

Of course, as in these kinds of cases, the issue is a lot more complicated. Basically, these little events are examples for the most part of deeper problems within the overarching set of building regulations that we have in DC with regard to nuisance properties.

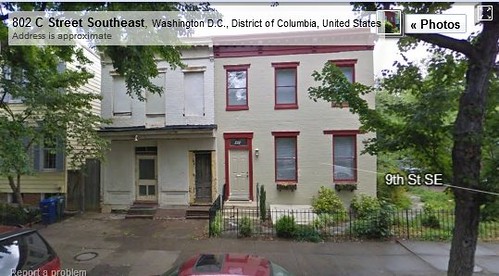

The demolition of this building is an odd case, a problem that arises from a Chinese custom of the extended family retaining ownership of buildings owned by deceased relatives because of the belief that their spirit is still present in the house, meaning that decisions about the property are not subject to normal kinds of regulatory and market forces that militate against nuisances.

In such situations, DC’s practices for dealing with nuisances, even in historic districts, are demonstrated to be inadequate. That’s the lesson here. Although the problem can be with any recalcitrant property owner, and have nothing to do with religion.

The problem is that the laws in the city are written relying on the goodwill of property owners to do the right thing. If the property owners aren’t so motivated, demolition is much more likely.

The one thing that the vacant property tax rate has done is move a number of property owners to sell.

But for people who for whatever reason aren’t subject to the laws of economics, even the vacant property tax isn’t enough.

Hence the demolition of this particular building.

If DC had a receivership statute providing for the seizure of properties in the case of notorious uncured nuisances, the demolition of this property wouldn’t have happened. I testified about the need for such statutes from 2002-2005 or so, but then I stopped because you can only repeat yourself for so long. (I will append sections of that testimony at the end of this entry.)

The thing that this particular case demonstrates also is that neighborhood organizations typically aren't positioned to be able to understand and globalize the issues and response properly, e.g., understanding how this problem reflects greater problems, and then mobilizing on a citywide basis to address it. Not to mention doing it.

Actually, CHRS is better on this kind of problem than most of the other neighborhood preservation groups because their interest area is greater than the strict boundaries of Capitol Hill, but encompasses the areas around and on the outskirts of the historic district, in undesignated areas. That's why they helped me on H Street issues with regard to historic preservation back when I was involved. They supported the creation of Main Street programs for Barracks Row (8th St. SE) and H Street NE, etc.

But still, there is a challenge with regard to identifying and rectifying broader problems, and gaps in local laws and regulations. That's why I became interested in receivership, because I came to believe it was the only way to address problems with buildings that couldn't be resolved by either the market or the enforcement of various building regulations.

From previous testimony to DC City Council on these issues:

1. Shortsighted nuisance abatement policies too often lead to demolition of historic properties.

Despite the demand for housing in DC’s core, many properties remain vacant, tied up by speculators who are aggressively unconcerned about how their behavior harms nearby residents and entire neighborhoods. Too often, demolition-by-neglect is used as a tool by speculators to assemble property for large-scale development and the conversion of predominately residential areas to commercial use. In the meantime, our neighborhoods are held hostage. When these buildings come down, it’s easy to think that since we have thousands and thousands of historic buildings, losing one doesn’t make much difference.

It does. Every demolished building becomes a vacant lot—negative space—defined by neglect.

Condemning a building and ordering it razed does not abate a nuisance. It simply creates a new nuisance just as persistent, damaging, and long lasting.

2. A Revised Nuisance Property Law is Necessary

In our opinion, the primary tool that the City employs to abate nuisance properties is demolition. Whether or not this is the intent of Council is unclear, but the fact is, by default, the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs is setting prevailing neighborhood stabilization policies through its regulatory activities, and their actions appear to lean towards the razing of properties, rather than the promotion of rehabilitation and habitation.

Not only does tearing down a property destroy unrecoverable assets, it creates a new nuisance in its place, one even harder to abate. While it is true that housing inspections, "Clean it and lien it" and other fines and sanctions exist, such sanctions have impact only if property owners are truly interested in maintaining the building. If not, a property owner prefers to let it rot, and fines will have no impact. A property owner committed to “demolition-by-neglect” can afford the middling fines. The fine for demolishing a building illegally is only $500–chump change to someone trying to build something new that might not otherwise be allowed. By contrast, consider that in San Antonio, fines and penalties for demolition by neglect and illegal demolition are set at the cost of reconstruction. “Market value” fines are likely to be strong deterrents.

While the DC Council passed a new law concerning vacant and nuisance properties, it is unclear how successful this law will be in practice. I am not hopeful.

(a.) The law puts great demands on the Executive Branch, particularly the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs, and it is evident through its words, deeds, and staffing that this agency is unable to meet these new demands.

(b.) Many DCRA inspectors lack critical expertise in assessing historic properties including critical structural engineering expertise, and they appear to be under-concerned about the importance of urban design and form. Given that more than one-third of buildings in this city are more than 60 years old, this knowledge deficit critically under-serves the city. The fact is, most properties can be rehabilitated, in most cases for less than the cost of razing and clearing a property and building new. To be fair to DCRA inspectors, they cannot be expected to know this if they aren’t trained in these assessment techniques, and if the system is stacked in favor of demolition.

(c.) The new law requires the identification and provision of monies to support the creation and operation of a revolving fund for property acquisition and rehabilitation. Money has not been forthcoming, paralyzing action in the interim.

(d.) Despite the existence of current laws requiring maintenance and habitability, many properties seem to escape the notice of inspectors for years and years, until finally the owner requests a demolition permit.

(e.) The Board of Condemnation of Insanitary Buildings, an entity within DCRA, is responsible for the abatement of nuisance properties but it tends instead to simply order their razing. Again, housing policies at the highest levels of the District government should favor the rehabilitation of historic properties, particularly houses, for many reasons. The “out of sight, out of mind” BCIB is perhaps operating in ways counter to the expectations of the City Council.

(f.) With regard to BCIB, it is troubling to discover that while this once was a board made up primarily of citizens, with a limitation of no more than one-third government officials, today the board is comprised predominately of government officials from DCRA, DPW, DHCD, and the Department of Administrative Services. Such officials are susceptible to lobbying by property owners and their representatives, and it is likely that these officials don’t always seek to have the properties independently evaluated by professionals with specific expertise in the stabilization and rehabilitation of historic properties.

While the Vacant and Nuisance Property Act does allow the District Government to take control of properties, this provision is unfunded, and it is likely that this authority will only be used once properties are too far gone to rehabilitate. In short, where are the real tools to take control of properties in order to stabilize and rehabilitate them, in situations where the owner has evinced no desire to maintain them in a habitable condition? This is especially important in DC where so much of the residential housing is attached. The beautiful rows of houses that make our neighborhoods so distinctive are endangered and adjoining residents are at special risk when a single row house becomes a nuisance.

Demolition punches gaping holes in the streetscape, and radically degrades neighborhood character. This kind of demolition of undesignated but eligible properties is going on all over the city and is counter to the neighborhood stabilization and improvement initiatives that the Council and Mayor endeavor to implement.

It is essential that the City Council revisit these issues. The Vacant and Nuisance Property Act and the Housing Act of 2002 are not yet enough to ensure that properties are being rehabilitated rather than destroyed. Agency actions need to be consonant with the desire revitalize neighborhood residential and commercial districts.

3. A Model Receivership Statute For Proactive Abatement of Nuisance Properties is Necessary

One way to address defects in current laws and regulatory activities is for the Council to pass legislation authorizing the appointment of independent receiverships able to take control of properties in order to abate evident public nuisances. Fines and inspections aren’t enough. And, the failure to fund the revolving fund authorized in the Vacant and Nuisance Property Act shows the necessity of identifying and allowing other interested parties to act proactively to revitalize and stabilize our neighborhood residential and commercial districts.

All the many activities that the DC Government is engaged in to restore our neighborhoods and bring people back to our city, from the City Living Campaign to the DC Main Streets program, are undercut by recalcitrant property owners who feel no obligation to maintain their properties. Acting only after a neighborhood suffers years of avoidable neglect fails all of us committed to a livable city.

I have lived in my neighborhood for most of 16 years. There are properties that were boarded up when I moved here – former corner stores and large and small houses, and commercial buildings on H Street–that are still boarded up today. Meanwhile a great deal of renovation is going on, and housing prices have as much as tripled due to increased interest and confidence in the neighborhood as a result of the construction of a new subway station on the northern edge of the neighborhood. But that has had little impact on absentee property owners with no motivation or desire to improve and/or sell their properties, or those trying to assemble large tracts of land for redevelopment.

(The new Class 3 property tax assessments will make a difference. But there are loopholes that property owners are using to avoid being categorized as a Class 3 property, and because these properties carry extremely low assessments due to their dilapidated condition, it may take longer than we wish to have the impact we are looking for—to have property owners put the properties back in play, because it is too expensive to let them sit.)

Nuisance properties degrade our neighborhoods and abet disorder. These “vacant” buildings tend to be problems and eyesores–places for illegally dumped trash to pile up and for loitering, squatting, drug use, prostitution and the like. With the enactment of a receivership law, these buildings can once again contribute to their neighborhoods.

The State of Ohio has a strong Receivership Statute that allows nonprofit organizations to petition the local Housing Court with a plan for the abatement of an identified public nuisance. (Ohio Revised Code; Title 37: Health-Safety-Morals; Chapter 3767, Nuisances; Section 3767.41, Buildings constituting public nuisance; action to enforce regulations; and receivership.)

The Cleveland Restoration Society uses this law to take control of properties that are being "demolished by neglect" and takes forceful action to stabilize and/or to fully rehabilitate the property. They are motivated to do this to preserve buildings in historic districts—but the effect is preservation and stabilization of Cleveland neighborhoods.

The Housing Court can clear title once the nuisance is abated, and the property can be sold to people who agree to live in and maintain the property. Covenants in the sales agreement ensure that the property will be maintained and protected. The best way to abate a nuisance is to fix it and get the house lived-in. Long term, receivership may be one of the best ways to preserve, stabilize, and revitalize our neighborhoods. And judging by how the program seems to be working, independent receiverships are likely to be more effective and more neighborhood-oriented and open to community participation than a program like the Home Again Initiative.

It is important to recognize that in Ohio, title is cleared only after the nuisance is abated. Too many nonprofit organizations in DC have been known for acquiring vacant properties, and then letting the property disintegrate further. In Ohio, receivership plans have deadlines, and unsuccessful receiverships are terminated, making it unlikely that the organization will be awarded receivership again.

Receivership could be one of the best tools we have to preserve houses—affordable houses—and neighborhoods in the District of Columbia. Without it there is no real way to force the hand of property owners who otherwise have no intention of maintaining habitable buildings. The option of receivership, with the ability to clear and award title to guarantee resale and habitation, would give residents and community organizations the ability to be proactive, rather than reactive and helpless. Besides, having the authority to force receivership will be a strong encouragement to absentee landlords to sell, rather than to sit on their property, and otherwise risk the chance of losing their property without gain. Either way, our neighborhoods win.

Labels: historic preservation, nuisance properties, receivership, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home