Georgetown and chains and branding (mostly a reprint)

The Washington City Paper Housing Complex blog has a piece "Why Aren’t Better Restaurants Coming to Georgetown?" on a recent forum in Georgetown opining about their position in the regional retail landscape. I've been wanting to write about it because of their recent exercise in branding, also discussed in the City Paper, "Georgetown's New brand: an anti-brand," and I wanted to contrast it with NoMA's new branding effort and others. I'll get to it at some point.

From the WSJ article:

In recent months, high-profile chains opening their doors in Georgetown include Calvin Klein Inc., North Face Inc., fashion retailer Rag & Bone, and, in May, Crate & Barrel's furniture and home-accessories store CB2.

Coming debuts include clothier Brooks Brothers, which is opening a 20,000-square-foot store in September, men's store Jack Spade and Williams-Sonoma Inc.'s West Elm furniture division, soon testing the market with a store on a six-month lease.

The new arrivals, with the national heft that allows them to pay higher rates, have boosted average lease rates for Georgetown's retail space. Anthony Lanier, founder and president of EastBanc Inc., which owns about 400,000 square feet of retail space in Georgetown, said the neighborhood's leases averaged $20 a square foot in 2000. Now, they range from $50 to $70 a square foot for large spaces and as much as $150 for small shops, he said.

"Ten years ago, Georgetown was a mom-and-pop market," said Michael Zacharia, a senior vice president in Washington for brokerage C.B. Richard Ellis Group Inc. "Now, we see national brands in the market and luxury brands looking to enter."

Is there a link between historic designation and chaining up of retail in neighborhood commercial districts?

Benetton, in the old National Bank of Washington Building at Wisconsin and M Streets NW, Georgetown. Another corner building at this intersection is occupied by Banana Republic. Photo by Dan Malouff.

Benetton, in the old National Bank of Washington Building at Wisconsin and M Streets NW, Georgetown. Another corner building at this intersection is occupied by Banana Republic. Photo by Dan Malouff.Catherine Magoulas, a student at Cornell, writes:

I have a question about the effect of historic preservation in Georgetown and its effect on the transformation of family owned businesses to corporate owned businesses. I was just wondering whether or not historic preservation itself is the cause/to blame for this movement. Any help on the matter would be greatly appreciated!

Richard Layman responds:

In my opinion, the answer is no. The transformation of the businesses in Georgetown results from as many as five different but interlocking trends.

1. The general dissolution of the independent retail business sector in the U.S. as the scale of stores and enterprise and nature of ownership within all sectors of the retail industry has changed significantly since 1950. A major piece of the change has been the consolidation of many regional and/or national chains into a handful of national chains, although in the past two decades the retail industry has been marked by the creation of large "big box" "category-killer" enterprises focused on a particular retail sector such as Home Depot in building materials and Staples in office supplies.

(This larger trend is illustrated by Macy's Department Stores, originally based in the NYC and SF regions, Two years ago it amalgamated a few hundred regional department stores into Macy's as the beginning of refashioning the company into a true national brand. This has been further accelerated by the acquisition of May Department Stores and the rebadging this year of independent regional chains such as Hecht's [East Coast], May Company [Missouri, Illinois], Marshall Fields [Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ohio] and others as Macy's branches far outside of the original NYC and SF regional footprint. This process has been going on for decades. E.g., in the early 1980s NJ and Brooklyn stores--Bamberger's and Abraham & Strauss respectively, were merged into Macy's, as were Boston's Jordan Marsh stores, as well as others.)

Change in retail has been massively accelerated by suburban outmigration. In the past forty years the amount of per capita retail space has grown by 400%, mostly at the expense of extant commercial space in the center city.

Cities that experienced decline, but not necessarily massive population decreases, such as the boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island in New York City, and places like Portland, Seattle, and Boston, were able to maintain more than a subsistence level of local retail and so today have a thriving, albeit competitive and ever-pressed, independent retail sector, which is now able to grow in response to demographic trends favoring urban living, because the social, networking, and economic infrastructure supporting independent retail never withered away in those communities.

IMO, within the last two decades Washington, DC has been a particularly excellent example of these broad trends of decline for both locally-owned independent stores as well as what were at one time substantial regional chains--companies like Raleighs, W&L, Hecht's, Britches, Ginns, Jacobs-Gardner, Lunch Box, Hot Shoppes have been either dissolved or merged into other larger businesses.

2. The trend of the scaling up in size and geographic reach of various retail enterprises and their location into large, even massive privately owned shopping centers for shopping-exclusive activities in a controlled environment,* has been complemented by the creation of a national and global commercial property market, with national and international corporations participating as developers and financiers.

(* If the original question was broader, not focused on Georgetown, then there would be six points, rather than five, and this point about the creation of single-owner developed shopping centers would be separated out as a unique trend. It's less relevant to the specifics of Georgetown, although I have written before about Georgetown Park and its relative failure as a "shopping mall," because it attempts to draw in customers off from "the street," into their controlled mall environment, when it is the life and vitality on the street that is Georgetown's greatest attraction.)

This trend has resulted from the same material circumstances that shaped the scale and nature of the retail industry.

National/International real estate companies seek national/international retail tenants, with the assistance of regional and national real estate brokers. Anthony Lanier's development operation in Georgetown is a perfect example of this (cf. the bankruptcy of the tenant Hollis & Knight in the "furniture-design" subdistrict created by Lanier interests), and his deliberate and successful seeking of national-international tenants such as Pottery Barn and others, which has come at the expense of locally-owned businesses, including even the Georgetown Seafood Restaurant owned by a local restaurant chain. (So much for a restaurant in Georgetown linked to the history of the community as a port town created decades before the District of Columbia was even formed...)

To learn more about Anthony Lanier, see

-- What does Anthony Lanier think it will take to revitalize Georgetown as a shopping district? Simple: It will take a village;

-- My Kind of Town: Don't blink. You might miss Anthony Lanier's next big move in his kingdom of Georgetown; and

-- Developer Infuses Historic Properties With Commerce" from the New York Times.

This process of reproducing the local retail environment into a national and international market with national and international retail chains as tenants is multiplied many times over by other developers in this city and elsewhere. (In malls and other shopping centers, something similar happens in the types of stores presented because the companies negotiate master national leasing agreements covering multiple locations.)

Carol T. Powers for The New York Times. Anthony M. Lanier, a Washington developer, has transformed Cady's Alley into a shopping area with a European flavor.

Carol T. Powers for The New York Times. Anthony M. Lanier, a Washington developer, has transformed Cady's Alley into a shopping area with a European flavor. With regard to the points in (1) and (2) above, I had an article about this although oriented to Dupont Circle, in the January Intowner, which is available online.

This is further exacerbated by changes in the financing industry and the ability of developers to "factor" (get financing based on) the leases of "credit" (national chains and/or franchises) tenants. Banks won't make loans on the leaseholds of independent businesses.

M Street in Georgetown has national chains such as Barnes & Noble, Johnny Rockets, Steve Madden, Smith & Hawken, Pottery Barn, Body Shop, Urban Outfitters, Ralph Lauren, Haagen Dazs, as well as prominent regional chains such as Dean & DeLuca. Photo by Dan Malouff.

M Street in Georgetown has national chains such as Barnes & Noble, Johnny Rockets, Steve Madden, Smith & Hawken, Pottery Barn, Body Shop, Urban Outfitters, Ralph Lauren, Haagen Dazs, as well as prominent regional chains such as Dean & DeLuca. Photo by Dan Malouff.3. Related to (2) is the impact of the DC property tax assessment model for commercial property, which treats neighborhood commercial districts the same way that properties are treated in the Central Business District (Downtown). Additionally, the property tax assessment methodology doesn't consider the use of the property, but merely the size of the lot, improvements, and the maximum development potential under zoning regualtions.

This further "produces" the DC real estate market into a national and international market, because the historic and/or eligible for designation properties in neighborhood commercial districts are not valued on the basis of their small floorplate and smaller retail trade area, but as if they are the same types of properties as those that typify the large office buildings in the Central Business District.

This results in seeming anomalies as the Takoma Theater being valued as if it could become condominiums, and ignoring the fact that the configuration and design of the building thoroughly shapes how this building can be used.

I testified about this before City Council twice (once extemporaneously when I serendipitously figured out this problem on the fly in response to a question by Councilmember Brown) and wrote about it in these blog entries:

-- Testimony -- Historic Neighborhood Retail Business Property Tax Relief Act;

-- Globalization of the DC real estate market catches neighborhood commercial districts up in the wake; and for the very first time in this blog entry from last year;

-- Displacement of retail businesses through increasing property tax assessments.

4. Probably the most significant aspect of Georgetown which has fundamentally changed the retail offer (or business mix) is touristification. Places like Charleston, Annapolis, Times Square in NYC, and Alexandria illustrate the same problem, and it is discussed in such tomes as The Tourist City by Judd and Fainstein. As the mix of customers has changed, the retail business mix has changed in response. Sometimes this is referred to as "Disneyfication." (See the syllabus for this course, "Tourism and Globalization," for relevant references.)

5. Finally, the Claremont Institute makes an interesting argument in one of their recent newsletters about the perhaps excessive regulatory "regime" in large cities. The cost of responding to and understanding various regulations is expensive, and this favors chains which can afford to (a.) hire commercial real estate brokers to represent them; (b.) develop in-house expertise to manage the process of dealing with regulatory agencies; and (c.) have the financial werewithal to withstand the regulatory process.

Bill McLeod of Barracks Row Main Street argues that it takes at least 18 months for an independent retail-restaurant business to open in DC, which is at least 6 months longer than in the suburbs. Eating rent and other opportunity costs for an extra 6 months or more is especially difficult for more lightly capitalized enterprises. (See this blog entry "It's hard to open retail businesses in the District of Columbia" -- -- for a link to the Claremont Institute article.)

East Carson Street, Pittsburgh. This commercial district is in a "weak" real estate market and thrives today, 20 years after being selected as one of the first five pilot programs to test the Main Street model in the urban setting. Pittsburgh is the site for the 2006 annual meeting for the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Photo: Project for Public Spaces.

East Carson Street, Pittsburgh. This commercial district is in a "weak" real estate market and thrives today, 20 years after being selected as one of the first five pilot programs to test the Main Street model in the urban setting. Pittsburgh is the site for the 2006 annual meeting for the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Photo: Project for Public Spaces.Actually, historic preservation, especially through the Main Street commercial district revitalization program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, is probably the best general assistance tool for the preservation of locally owned businesses in neighborhood, town, and downtown commercial districts.

What historic preservation-based urban revitalization strategies do is provide a way to expand the customer base from beyond the immediate neighborhood or city. This is necessary because for the most part center city business districts have been supplanted by regional shopping centers that draw upon much larger retail trade areas. However, this is controversial because many residents believe serving the neighborhood should be the primary goal. Yet this ignores the difficult economics presented by micro-sized trade areas--not enough revenue and customer base to support unique offerings (this is discussed in greater detail in "(Why aren't people) Learning from Jane Jacobs").

The trick is to manage this process in such a way that authenticity is maintained rather than diminished. Georgetown has already lost this battle, partly because property owners such as Anthony Lanier have a deliberate strategy to "re"produce the retail mix towards a different demographic, and also because when people visit Washington, Georgetown is the primary tourist destination after people have finished their visits to landmarks and museums. (17 million+ people visit Washington each year.)

Because visitors to Georgetown comprise more than 50% of the customer demographic, rather than residents living within a 3-5 mile radius, the retail and restaurant business mix has been reshaped to meet the needs of visitors. Because the size of the visitor segment is so massive, it has overwhelmed the ability of authentic businesses and experiences to present viable business models in the face of rent and other pressures.

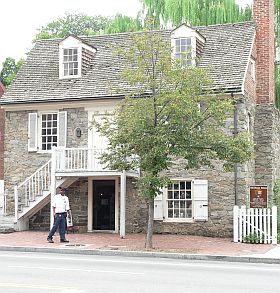

Old Stone House, Georgetown. This building, the oldest extant in Georgetown, is out-of-place in a community where the sense of place provided by architecture and history has been supplanted by the experience of Georgetown as a place to shop or play, irrespective of historic elements.

Old Stone House, Georgetown. This building, the oldest extant in Georgetown, is out-of-place in a community where the sense of place provided by architecture and history has been supplanted by the experience of Georgetown as a place to shop or play, irrespective of historic elements.Finally, Georgetown is further stressed by its prominence as one of the city's leading evening entertainment destinations (although places like U Street and Adams-Morgan are now seen as more hip). For the most part, Georgetown's residents don't typically "consume" this aspect of the commercial district's retail offer. Georgetown's verve started with the Kennedys living in Georgetown back in the 1950s..., but the trend continues. See "Bush Twins turn Spotlight on Bar" for one small example of this.

Michael Nagle for The New York Times. WINNER'S CIRCLE Young Republicans at an afterparty at Smith Point, a bar in Georgetown, on Inauguration Night. From "Bush Twins Aside, the Party's Here."

Michael Nagle for The New York Times. WINNER'S CIRCLE Young Republicans at an afterparty at Smith Point, a bar in Georgetown, on Inauguration Night. From "Bush Twins Aside, the Party's Here." Charles Ommanney / Contact for Newsweek. Smith Point: Center of D.C.’s preppy nightlife. From "Jesus and Jack Daniel's In search of the Bush cultural footprint on the capital: a visit to the hot church and the hot bar," Newsweek. (This article provides good insight into how spaces are "reproduced" to reflect new conditions.)

Charles Ommanney / Contact for Newsweek. Smith Point: Center of D.C.’s preppy nightlife. From "Jesus and Jack Daniel's In search of the Bush cultural footprint on the capital: a visit to the hot church and the hot bar," Newsweek. (This article provides good insight into how spaces are "reproduced" to reflect new conditions.)The reality is that Georgetown has become a regional commercial district-destination, and its retail offer has changed to reflect this. That is the overall trend that encompasses all the others, and is unrelated to the fact that the neighborhood has been designated as a historic district. (Although I suppose it can be argued that the attractiveness of Georgetown to broader customer segments has resulted in part from the preservation of the historic architecture and urban design that contributes to the distinctive sense of place that Georgetown possesses.)

One of the factors this changes is the prevailing rents, which climb to a point that prices out neighborhood-serving businesses, because such businesses generate reduced revenue compared to businesses selling higher priced items to a larger customer base. Also see this blog entry from January, which comments on the "displacement" of art galleries from Georgetown: "Authenticizing Inner Harbor and maybe thinking about authenticity and Georgetown DC."

The current "battleground" over commercial authenticity is 14th and U Streets. This reviving commercial district has seen the addition of a number of chains, but at the same time this area is becoming the center of the city's local retail entrepreneurialism.

Compare this to the somewhat anemic commercial offer in the Greater Capitol Hill area because of the relatively light population density, and the limited attraction to non-area residents (with the exception of the Eastern Market district on weekends), which has meant that the area isn't overly attractive to chains (Starbucks, CVS, Quiznos) although more are coming (Dunkin' Donuts, Harris-Teeter). But this means that most retail remains independently-owned, however, the number of retail categories represented is quite limited.

For other resources on some of these issues, highly recommended is the article "Main Street at 15," by Kennedy Smith, and published in 1995 in the National Trust's Forum Journal. Also, Cities: Back from the Edge by Roberta Gratz is particularly excellent about this general point of preserving local business sectors as a fundamental part of historic preservation-based urban revitalization methods. (Also see Community Economic Development Handbook by Temali, and maybe Organizing for Community-Controlled Development published by Sage.)

Carol T. Powers for The New York Times. Historic buildings along M Street in Washington that had fallen into disrepair have been rehabilitated and turned into elegant shops. See "Developer Infuses Historic Properties With Commerce" for a larger version of this photo.

Carol T. Powers for The New York Times. Historic buildings along M Street in Washington that had fallen into disrepair have been rehabilitated and turned into elegant shops. See "Developer Infuses Historic Properties With Commerce" for a larger version of this photo.With regard to thinking about historic preservation, perhaps we should ponder the lyrics to a song by Eric Clapton:

It's in the way that you use it,

It comes and it goes.

It's in the way that you use it,

Boy don't you know.

And if you lie you will lose it,

Feelings will show.

So don't you ever abuse it,

Don't let it go.

Developers like Anthony Lanier "use" historic preservation in a fundamentally different fashion from the East Carson Main Street program in Pittsburgh. And in many respects, this comes down to the exchange value of place versus the use value of place. (See Urban Fortunes: A Political Economy of Place by Logan and Molotch.)

To repeat something I say all the time: the elements of DC's competitive advantage are architecture, urban design, and history. Any time public policy or the practices of private developers diminishes the value of these elements, the competitive advantage of the center city also diminishes.

Labels: commercial district revitalization planning, formula retail, historic preservation, neighborhood planning, urban revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home