DC's Martin Luther King Library back in the day...

Is a trying issue because the building was designed to be an office building, not a library, and it was designed in a way that would be very expensive to maintain, in a manner that local governments aren't typically capable of managing, not unlike the failure of the City of Tampa to maintain a famed open space designed by landscape architect Dan Kiley (see "

The Life and Death of a Masterpiece: What went wrong with a 1988 park by the late Dan Kiley, and what can we learn from its imminent demolition?" from

Landscape Architecture).

Even though the North Carolina National Bank Plaza was designed by a master, masters don't always create practical projects. From the article:

From modern masterpiece of landscape architecture to ruin, from a public/private civic asset to a blight on downtown Tampa, how did this place devolve? That there was a major failure of maintenance is not in doubt. But was inappropriate design also a factor? Were the park's hardscape features—pools, canal, runnels, fountains—overdesigned? Given the site conditions, were the plantings too dense or the wrong species? Did they require an unreasonable amount of maintenance? Was responsibility for maintenance vague, divided, or unspecified? Was the park too ambitious for downtown Tampa? Was it doomed from the outset because of constraints imposed by its location? Or by inevitable changes that would follow in a city in need of revitalization? And who is to blame for failure: the designers, their clients, the city, or all three?

In the case of the Kiley park in Tampa (also see "

Renowned architect restores Tampa's famed Kiley Gardens" from the

St. Petersburg Times), all of these problems--overambitious design, problems with execution, problems with maintenance, and the role of the public realm and the civic in increasingly privatized spaces--come up in the consideration of DC's Central Library.

The presentation yesterday by the ULI panel (

Powerpoint, "

Can the Martin Luther King Library be shared?" by Mike DeBonis of the

Washington Post and "

Panel suggests options for reviving MLK library" in today's

Post) was fine, but for people who have been involved in the issue of the library for awhile, what the ULI panel thought of as "the beginning of a conversation" is in fact 11 years into the conversation, and like the terms of the engagement for the ULI panel, too often this conversation has been one-sided, amongst the DC Library Board of Trustees and their fellow

Growth Machine friends and stakeholders, and not so much with "the community."

These are resources from the 2006 iteration:

The one thing I learned from the presentation yesterday is that the ULI engagement was kind of a setup. The reason that the library has made the statement that it only needs 225,000 square feet, is that the Library building as it is now is larger than that, and has the capability of being expanded further, by adding floors.

This sets up a scenario for either selling the building, and "rightsizing" in a new library or for expanding the library but renting a considerable amount of space to rent paying tenants and in all likelihood the tenants would be trade associations, law firms, and the like--the typical tenants in DC's downtown office buildings today.

Sure people in the audience thought that co-locating nonprofit and arts tenants might make sense, but those kinds of tenants can't pay market rental prices ($50 to $75/square foot).

Unlike what I say in my quote in the Post article:

“You got the Verizon Center, you have the museums . . . you have the convention center. There is this renewed energy — continued energy — and why shouldn’t we say that the civic is important, not just the commercial?”

I actually am torn about the building. I don't know if it can be cost-effectively renovated and made great, although the Kent Cooper proposal avers that it can be.

But I do believe that the Central Library should be downtown and why not at that site? '

Today the Library is surrounded by an increasingly vibrant downtown, its location is now a prime one, across the street from two Smithsonian Museums and near the Verizon Center, and within a few blocks are more than two dozen other cultural assets, ranging from the Carnegie Building and the Goethe Institut and the German-American Heritage Museum, waning Chinese assets in "Chinablock," to the National Building Museum, two different facilities for the Shakespeare Theatre, the Spy Museum, etc.

This area is now the city's premiere cultural district once again, although we don't have a master plan for it (as a model I am thinking of the plan and program of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and their management of cultural facilities in Downtown Pittsburgh).

(Note though as a cultural district it needs to be managed in a concerted way, more than just through the Arts on Foot Festival every year.)

Why shouldn't the DC Central Library, with a great program, and extended hours even beyond 9 pm, be located in that district, right where it is today? (The

Bibliotheque and Archives Nationales in Montreal is closed on Mondays, but open from 10am to 10pm Tuesday through Friday, and from 10am to 6pm on Saturday and Sunday.)

The issue does come down to what is the role of civic in the city.

Today, most of the focus is on maximizing the revenue value of each square foot of land and development rights, especially in Downtown, the central business business district, which is one of the strongest commercial real estate markets in the world--it's a focus on commerce and profit, not civic life.

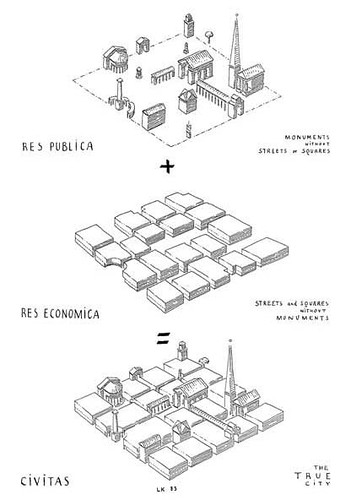

Architect and author Leon Krier (see the

Architecture of Community,

article by Howard Blackson on the book) writes about how the city ("civitas") is the combination of the public ("Res publica") and the commercial ("Res economica"), but that a civitas cannot exist if the city overfocuses on one sector at the expense of the other.

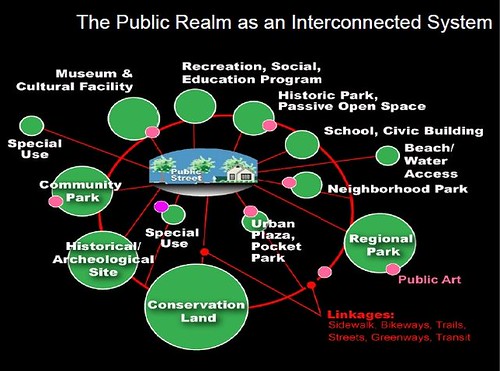

Similarly, David Barth's writings about park and civic planning considers civic assets to be the fundamental building blocks of quality of life in the community.

What are the most important public-civic buildings in a community?

Thinking about the City Beautiful Movement, which was a focused program using architecture and design to build civic identity, it's important to ask ourselves what have been considered, historically, to be the most important civic buildings and spaces within a community.

This list isn't absolute, but in any case, the main library either comes second or third, and is one of the most highly used buildings within a community ("

Libraries love everyone" by Sarah Sugden, downloadable pdf):

1. City Hall

2. Courthouse

3. Library

4. Railroad station (privately owned but decidedly a public building. Airports have since replaced this building as a central one, but at the same time since airports aren't located within communities anymore but far outside of them, these facilities don't have the same kind of force in civic identity that railroad stations--located in the heart of the city--once did)

5. Public auditorium/Civic Center

6. Arts Museum

7. Signature public park

8. Baseball stadium (usually privately owned but a public building in terms of substance)

9. Public Market

We also have to include the most common federal building typically located within a community:

10. the Post Office and/or Customs House

and depending on the size of the community:

11. Federal Court building

Religious buildings (churches and cathedrals) and school buildings are also key buildings defining community at both the scale of the city overall as well as within neighborhoods. Branch libraries and parks have this function as well.

Key commercial buildings defining civic identity and the importance, prominence and centrality of commerce within a community include the main department stores, movie theaters, the central business district generally, the tallest buildings specifically, the major banking institutions and the commercial buildings of leading companies based in the community, the local newspaper, etc.

It is a fair question to ask of ourselves, isn't the role of the central library within our community important and key to civic life, and therefore shouldn't this building remain at the core of the city, in the center of the city?

Maybe the library system is right that main branches are shrinking across the country, but if that is the case, it's not true of the country's major cities (NYC, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, etc.), which are the cities that DC, although it is only

the 24th largest city in the U.S. in terms of population, usually compares itself to and measures and benchmarks its public functions and activities against.

Syracuse does want to rent out some of its city hall that it doesn't use to make some needed cash. See "

Syracuse sets new policy for city hall rental," from the

Syracuse Post-Standard. DC is small, although bigger than Syracuse. In any case, Syracuse doesn't set the standard to which DC claims to aspire.

In the country's major cities, the central library isn't a building where the space is shared with commercial tenants. The library is seen as an important and central function in and of itself.

And it does seem a reasonable question to ask, when the Mayor and other elected officials jet off to Tampa, in preparation of a proposal to give a practice facility to the region's professional football team, how should we be spending the city's money, and isn't maintaining a prominent central library one of the most important places where this money should be spent?

Labels: arts-culture, civic engagement, land use planning, libraries, mixed use, real estate development, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home