DC and the zoning rewrite and the approach not taken

Yes DC is really two cities on a number of metrics.

- In terms of race: the African-American city vs. the "white" city of "The Plan.

- In terms of wealth: it's a city of above-average incomes juxtaposed with communities of terrible poverty.

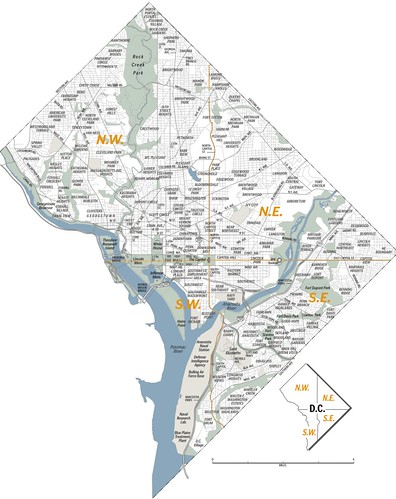

- From the standpoint of urban design, it's also two cities; the denser urban city at the core, not fully limited to "the L'Enfant City of Washington" as designed by Pierre L'Enfant in 1790-1791, because the denser city extends northward outside of the original boundary of Florida Street (then Boundary Street); and the outer part of the city that was originally "Washington County," and decidedly rural.

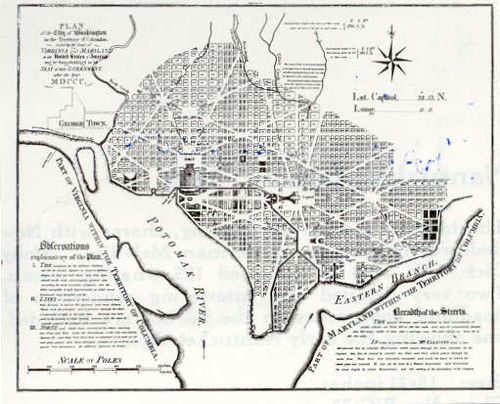

The L'Enfant Plan for the City of Washington covered a small portion of the city. The complete map of the city below is depicted in a Washington Post image.

As the city grew, the county and city were consolidated (this occurred around 1890). The street network in what had been the county was rationalized to conform to the L'Enfant City in terms of blocks and an "orthogonal" street grid where the north-south streets matched up for the most part with the streets in the already developed city.

The two different "cities," from a spatial standpoint, reflect the time period when the respective parts of the city developed. L'Enfant's city was designed during the era of "The Walking City," when most people lived close to where they worked, because people were limited to foot or horse for mobility. This period lasted until around 1880.

From 1880-1920 was the era of the "Transit City," as the development of streetcars extended the range which people could travel relatively quickly. But the basic design was no different, with streetcars following radial routes (L'Enfant's "avenues") outside of the core of the city, allowing for quick trips over comparatively long distances. (I once heard a story of a person who had been a student at Gallaudet University in the 1940s who said he could get from H Street to Rosslyn, Virginia in 15 minutes--probably a stretch, but still...)

From 1920 forward, development patterns in DC (and elsewhere) have been shaped by the automobile.

This meant that starting in the late 1920s, new house construction included "accommodations," parking, for an automobile (houses were developed with garages for cars, even rowhouses and corner houses without alley access, in neighborhoods like Petworth, Manor Park, and Takoma), even while the road pattern continued to follow the traditional pattern of the street grid, with relatively small blocks (about 300x300, about 1.5 acres). And commercial buildings and districts had to be outfitted with parking, whereas earlier, people shopped by walking, bicycle, and transit, and were supported by delivery of goods as well.

Rear entrance basement garages, rowhouses, Brightwood.

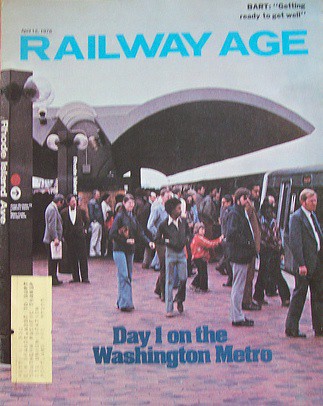

- Even though the city once had a relatively extensive streetcar system, by not agreeing to renew the franchise, Congress forced the end of the streetcar system in 1962. It was replaced, eventually, by a subway system that first opened in 1976.

From the standpoint of transit, DC is a city with a subway system, but many neighborhoods are not served by transit. So it's a city of transit users vs. automobilists. This is complicated by the fact that the outer part of the city, developed after 1920, is much less dense and therefore, comparatively "spread out."

So in that part of the city most households rely on the automobile, not transit, to get around. For example, on our face block there are about 24 houses and we're the only household without a car (most of the households with two adults have two cars).

In a paper I wrote in 2007, I made the point that even though the subway system is a polycentric design, and focused on bringing suburbanites into the city for their federal jobs, at the core of the city the subway system functions monocentrically as a subnetwork, for the residents and neighborhoods served by the core of the subway system. (This blog entry outlines the argument.)

Then, I said that this subnet is comprised of 29 stations, from Foggy Bottom on the southwest to Stadium-Armory on the Southeast, to Van Ness on the northwest, and to Brookland on the northeast.

Now, with the redevelopment of the areas around the Waterfront Station in the Southwest Quadrant, and the development of the "Capitol Riverfront" District along M Street SE adjacent to the Navy Yard and the Navy Yard Station, the area served by those two stations needs to be added to this subnetwork catchment area, making it 31 stations comprising the city's monocentric subnetwork (the system has 86 stations total) of the subway system.

It is no mistake that without exception, even if it has taken decades, that all of the neighborhoods served by these stations are stable or improving.

Anyway, what does this have to do with zoning and the zoning rewrite?

1. The zoning rewrite recommends that in areas served by transit, that parking for automobiles won't be required.

2. This gets people, primarily in the areas of the city that are much more "car-dependent," all worked up. It could be to the point of meaning that the proposed rewrite will fail in the face of citizen opposition.

- Back to the "two cities" theme, you can argue that another meme is "new residents" vs. "old residents" in terms of opinions about the city and how it should develop from the standpoint of urban design. There are a number of reasons for the difference in opinion:

- The primary development paradigm in the county for almost 70 years has been around single use zoning, development of the suburbs, and the focus on the automobile as the main mode of transportation.

- What most people don't realize is that they are imprinted with this paradigm even if they aren't conscious of it and they apply it to center city matters, not recognizing the paradigm's inappropriateness for application in the city setting.

- The "old residents" focused most of their civic energy on stabilizing a shrinking city--the city was losing population, especially of people with income, and municipal institutions (for a variety of reasons) began failing. Their focus was on "preserving" neighborhoods, and that remains their heuristic for approaching issues as the city has the opportunity to grow. In short, you could term the approach as pro-automobile and no change.

- New residents aren't shaped by past battles, don't know much about that history and aren't necessarily attracted to the city out of a sense of stewardship for its architecture. And increasingly, their preferred mobility modes are walking, biking, and transit, and they'd rather not own a car (but are fine with shared cars).

That makes it almost impossible to develop consensus about how to handle the opportunities that the city has to grow and add population.

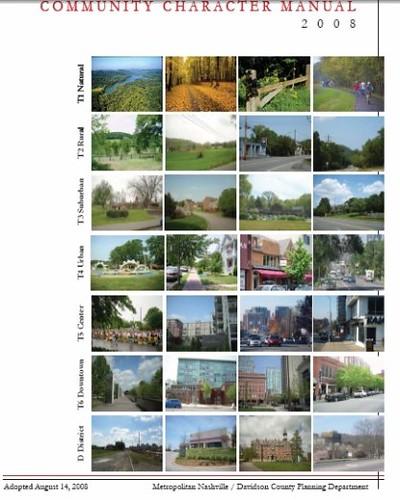

A few years ago, I suggested to someone in the team handling the zoning rewrite that the city should consider the framework offered by the Nashville Community Character Manual.

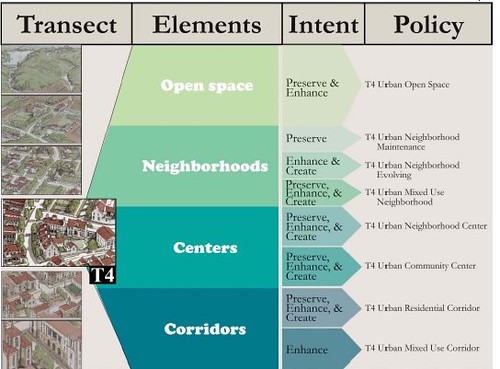

The Nashville document is based on the New Urbanist "transect" of six basic land use contexts, from very rural to dense urban.

This illustration from The House Book by Keith DuQuette is a reasonable rendition of how the New Urban transect works.

What the Nashville Manual does that the transect does not is drill down within the transect zones in a practical fashion, and creates sub-zones within each "T" zone.

It does this by looking at the four main types of land use (open space, residential [neighborhoods], commercial [centers], and corridors) and the preferred intent for how to "use" the land--preserve, enhance, or develop it, through the development of policies for subzones within each T zone.

Most of DC is T4 to T6. In the Nashville Community Character Manual, those transect zones have a total of 17 subzones. This makes it possible to provide better and more targeted zoning and planning guidance. It means that the theoretical (the New Urban Transect) is translated into the practical.

Since nothing seemed to happen with my suggestion, I figured it was blown off.

It turns out that the Office of Planning spent a fair time researching it, and determined that this type of approach made sense for DC.

They proposed using a similar character zone framework to the Zoning Rewrite Advisory Committee, which turned out found the concept too radical or hard to grasp.

Because of the Advisory Committees rejection, this approach was abandoned.

And so the mess and fear of change continues.

Labels: land use planning, neighborhood planning, transportation planning, zoning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home