Remembering why we build transit underground: because the surface is congested

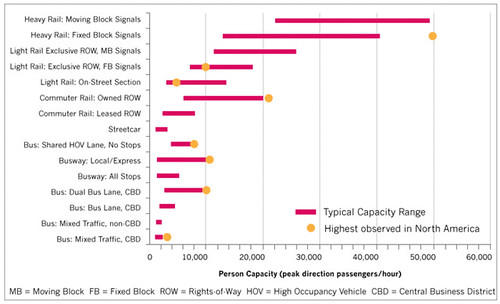

Person-capacity ranges for various transit modes.

Adapted from TCRP 100 Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual – 2nd Edition, 2003, page 1-21. As discussed in the Ontario Ministry of Transportation Transit-Supportive Guidelines, Section 3.1.1 Transit Service Types. Transit ridership capacity varies according to mode, the signalization and control systems under which it operates, and whether it operates in mixed traffic or on dedicated transitways.

In a project I am working on, the project manager spent a few years on assignment in Shanghai. We were talking about streetcars in DC, and he countered with his experience in Shanghai, which as a hyper-populated, hyper-dense city, movement on the surface is particularly slow, because there are so many people and vehicles.

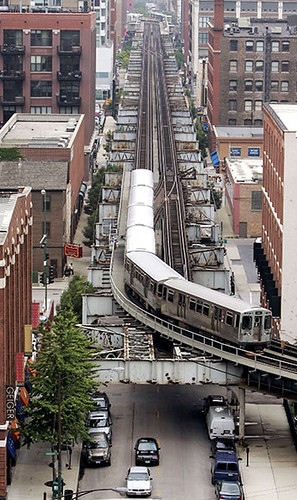

Chicago Elevated train. Photograph: Rex Arbogast, Associated Press.

Chicago Elevated train. Photograph: Rex Arbogast, Associated Press.So like in the days of old, to have unfettered movement, you create subways (underground) or elevated (el) lines ("The Last El Train" from the New York Daily News; in the core of Downtown Chicago, the heavy rail train, the "L" or "El" for elevated, still runs above ground) so that you don't have to worry about conflicts at the surface.

I countered that in DC, we aren't hyper-dense, so streetcars won't have exactly the same issues here, although they do need to have traffic signal priority and in the core of the city, dedicated transitways, in order to make movement of these vehicles more efficient.

But still, there is no question that in cities, to enable more intense development, more, especially high capacity, transit is necessary.

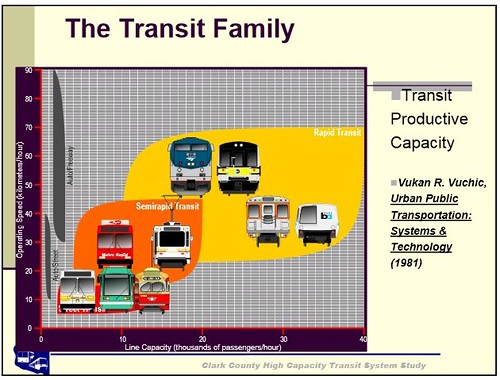

Semi-rapid vs. rapid transit

In denser places, the best bet, expensive as it is, is underground transit--preferably, but is very expensive because of tunneling. Overground transit--in the air--creates visual blight and can be hard to do also, if the air space for train routing doesn't exist.

That's captured in this diagram from a presentation for the Clark County High Capacity Transit System Study (Vancouver, Washington). I like how they group the various modes into two groups: rapid and semi-rapid. (It would be useful to have one master diagram that includes automobile lane capacity as well, if only to have the same basis of comparison and to drive home the point that transit moves a lot more people for the same amount of space than does a focus on automobility.)

Rapid transit is both faster and has more ridership capacity. Typically rapid transit is for longer trips. Semi-rapid transit can be and is used for longer trips, but is also more focused on what I call intra-city transit (see "Making the case for intra-city (vs. inter-city) transit planning").

(Toronto's problems with transit expansion concern the reality that suburbanites want "better" transit, that is, heavy rail, but they lack the population and employment density to financially justify it. And because the suburban portion of Toronto dominates the urban core, not unlike the situation in Washington, see "DC as a suburban agenda dominated city," improvements in the core are held hostage to the suburbs.)

Midtown Manhattan will need more rapid transit if development capacity is increased

This is an ongoing issue in Midtown Manhattan, where the Real Estate Board of New York has been egging on the Bloomberg Administration to upzone the area, which is already at maximum capacity utilization for transit. I wrote about in February, "More on Manhattan."

It comes up in the New York Times from Thursday, "The plan to swallow Manhattan," and a blog entry, "A transit opportunity, slipping away, arises with Midtown rezoning plan,"in Second Avenue Sagas.

The basic point they make is the one I made in my entry a few months ago, that without more transit, adding more density--irrespective of the issues about demand and competition within Manhattan and Brooklyn with other, difficult and complex, massive developments--is crazy.

From the Times article:

New York can surely never win a skyscraper race with Shanghai or Singapore. Its future, including the future of Midtown real estate values, depends on strengthening and expanding what already makes the city a global magnet and model. This means mass transit, pedestrian-friendly streets, social diversity, neighborhoods that don’t shut down after 5 p.m., parks and landmarks like Grand Central Terminal and the Chrysler Building.

If New York wants to learn from London, Tokyo and Shanghai, the lessons aren’t about erecting new skyscrapers. Big cities making gains on New York are investing in rail stations, airports and high-speed trains, while New York rests on the laurels of Grand Central and suffers the 4, 5 and 6 trains, which serve East Midtown. They carry more passengers daily than the entire Washington Metro system.

Improving the lives of the 1.3 million people riding those trains would instantly make the city more competitive. Adding thousands of commuters who work in giant new office buildings without upgrading the surrounding streets and subways — the Second Avenue subway won’t do it — will only set the city back.

Left: Flickr photo of Downtown DC by Otavio_DC.

Downtown DC, financing transit capacity expansion, and the building height limit

While DC is nothing like Shanghai or NYC, even so in Downtown, the transit system is forecasted to reach capacity in the next decade.

Because of various compromises that have to be made between the jurisdictions to justify their involvement and payment for expansion, there is no support for intra-jurisdictional payments to address the problem. Instead, the problem is seen as DC's. (By 2050 the Metro Momentum Plan forecasts significant capacity expansion in DC, which will be about 60 years after I wrote a long letter about this issue to the first Washington Post Dr. Gridlock columnist.)

-- Metro Momentum plan

That's why DC shifted its transit expansion focus to streetcars, which are more a technology for intra-city mobility improvement, because officials figured they could finance streetcars, but they wouldn't be able to pull building a new subway line, especially because the likelihood of special funding coming from the Federal Government is extremely unlikely. (Special funding from the Federal Government did pay for a large portion of the original subway system.)

The link between real property value and the capacity to issue municipal debt

Commercial property generates the bulk of a municipality's tax revenues. To pay for heavy rail transit expansion in the city generally, and especially in the core, probably the Building Height Limit will have to be increased. See "Study: Raising D.C.`s height limit would help city, not cause world to end" from the Washington Post.

-- Height Master Plan, Economic Feasibility Analysis

Higher property values will allow the city to increase the amount of debt issued--and it would cost billions of dollars to build the separated blue line, let alone other heavy rail transit expansion--without violating current covenants on bonds limiting debt to 12% of the city's budget.

Similarly, Portland funded the creation of the Yellow Line (Interstate MAX) light rail by creating an Urban Renewal District, and selling bonds--based on the likelihood of increased property tax revenues over time--to build the line.

Surface transit schemes in dense places: Select Bus Service in NYC

Getting back to the point about surface transit improvement schemes like "bus rapid transit," the reality is that especially in dense places, without dedicated transitways such as the creation of transit malls in a city like New York, improvements in surface transit might not have all that much return in terms of time efficiency. But they can make getting around more convenient.

-- "Subway on the Street," New York Magazine

-- "How Manhattan Sped Up its Buses Without Rapid Transit," Atlantic Cities

By giving up traffic lanes to buses or streetcars, especially in Manhattan or in Downtown DC, throughput can be significantly increased, as pictured in the NYCDOT photo below, where bus lanes are being painted in special colors.

But we have to recognize that intra-city transit issues are different from inter-city transit issues.

Like DC, NYC has other issues because they don't control most of their transit, except for ferries.

The bulk of the transit serving NYC is delivered by a state agency, the Metropolitan Transit Agency (it used to be controlled by the city, but after NYC's bankruptcy in the 1970s, control shifted). So local officials end up focusing on ferry and buses, because they have more opportunity to shape those services.

Second Avenue Sagas has another entry, "Brad Lander’s ‘Bus Mayor’ and the Triboro RX SBS plan," about the proposed Triboro rapid train, which could mostly be created by using existing routing, and Mayoral candidate Christine Quinn's proposal to do this service as bus rapid transit. Also see "Quinn Proposes Triboro BRT Line With Separated Bus Lanes" from Streetsblog.

Breaking through the logjam of lack of funding to build more rail--ironically, New York City merged the five boroughs in order to increase their capacity to sell bonds, so they could fund the creation of the subway system--is almost impossible in the current political climate nationally, and at the local-state level, because most state legislatures seem to be dominated by exurban and rural interests.

So cities, even very dense cities like NYC, end up seizing on transit that they can pull off, like "rapid bus" and streetcars, and continue to kick the can down the road about heavy rail expansion.

If big city officials were smart, they'd justify (and tie) upzoning proposals to creating the funding mechanisms for heavy rail transit expansion

If Mayor Bloomberg would begin to tie upzoning proposals in places like Midtown Manhattan as the way to pay for heavy rail transit expansion, it would be very difficult for historic preservationists and transit advocates to oppose it.

I think that's what's going to end up happening in DC, if DC officials can get it together and accept that transit is essential to the city's economic competitiveness and positioning. NYC already understands this--although their ability to create policies and programs is hampered by their need to get approval from the State Legislature, which is dominated by rural interests and general animus towards "The City."

Tie approval of a building height increase in downtown to a plan and program for heavy rail transit expansion in the city, and it will be hard for most residents, stakeholders, and advocacy groups to oppose the change.

Labels: commercial real estate market, public finance and spending, transit infrastructure, transportation planning

9 Comments:

Hi Richard,

I took the aerial photo of downtown DC in this post.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/otavio_dc/2386087485/

Otavio

I had the opportunity to drive up Georgia the other day to Military. Reminded me of driving in DC 15 years ago as compared to the rest of NW.

(and that is probably related to the lack of development)

In terms of DC proper, same problem as NYC in that the city doesn't control WMATA. Not sure there is an easy way around that.

In terms of looking at examples looking at Arlington is a good demo of how traffic won't get as bad as the model suggests. That being said, you need to make a heavy investment is the roads at the same time to support the increase in road traffic that will happen and find ways to get people not to drive (circulator, bike, etc) I feel Arlington was really behind the curve on that stuff (turns lanes, lights). DC, as usual, is way behind the curve and when the try to fix it (Glover park improvements) it has turned into a disaster.

THe idea that "downtown" DC is built up is a straw man as we keep expanding downtown, something that can't be done in Manhatten because of the size of the office buildings and land acquisition costs.

Otavio -- thanks. When I get access to my account later in the day, I'll change the caption.

R

charlie -- it is amazing at how certain chokepoints have disproportionate negative impact on throughput. As we discussed before, it's what made me appreciate more than I used to the concepts of ITS.

Blair Road at Riggs used to have a 15 second signal going south. (Now it's closer to 26 seconds). Because oncoming traffic gets a longer light and both turns right and goes straight, since there is one lane proceeding south, left turning traffic bottles up the intersection and during rush the traffic builds up for a couple blocks.

Similarly, having some cars parked in the right most lane at Georgia and U Street going south, combined with left turning traffic plus buses needing to go around the parked cars, this intersection is really bad way more than it used to be.

I think the real impact of the increase in population and the use of cars is on these kinds of chokepoints.

... except if you are a bicyclist.

Which is why I need to write a letter to the editor in response to last week's Current editorial on more laws on bicyclists.

p.s. charlie, wrt DC not taking steps to improve throughput, also see the failures to take up ideas such as laid out in the LTR response I did for the Walmart on GA Ave., when we recommended that the intersection be reconstructed.

DC needs to do this in lots of places and isn't.

@Richad, yes, I think DDOT is not being proactive here.

Or using the wrong metrics; for example on the L st bike lane looking at it form "how long does it take to ride/drive the entire thing" when the issue with the bike lane is turns and midblock cut throught for parking garages. Hazardous for everyone.

one of the points I make about design and engineering is what I call "designing conflict in" vs. "designing conflict out."

The point, i thought, of traffic engineering is to design conflict out. Too often, we design it in.

Mostly, when people complain of various traffic/intersection problems, they are the result of either bad design or not making better decisions about what to prioritize. (E.g., as you get closer to U Street going south, say mid-block from V Street, the parking should be eliminated to prioritize throughput. Even if that seems anti-placemaking. Or, road space is precious. Would you rather it be used for car storage, or a transitway? Etc.)

The L St. cycletrack as you point out has designed in conflicts between turning motor vehicles and loading zones and the cycletrack.

I ride it to be supportive but I probably prefer to ride in the street.

I don't have a better alternative other than a middle lane dedicated to cyclists combined with a bike box so bicyclists can move over at the intersections as needed.

That creates a snow removal problem and such. Or to do real separation and to force the delivery zones and loading zones to the right of the cycletrack, which would be the optimum but create other problems.

----

When I was doing research for this piece, I thought I downloaded but seemed not to, an image that put the ridership capacity of various modes along with road capacity for motor vehicles, in various situations. The best you can do per lane mile is about 2,200 vehicles on a freeway. When you get into cities, I think the avg. number is about 800 vehicles per hour, and it's about 1300 vehicles per hour in suburban arterial settings.

I read this post minutes after reading this story about transit in the Route 7 corridor in VA: http://www.wtop.com/41/3403163/Mass-transit-could-improve-Route-7-traffic-

Seems like tunneling is the only plausible solution to high-capacity transit in that corridor, as an extension of the Purple Line. Too bad this article convinced that congestion will ever be "solved." There can only be alternatives at this point if population remains constant...

my article or the wtop article argues that congestion can be solved?

In the city, it "can" by shifting trips to sustainable modes...

I remember reading an interview with Jane Jacobs after _Nature of Economies_ came out. She was asked about congestion. The Q was "why aren't there enough roads?" She countered: "you're asking the wrong question. The right question is 'why are there so many cars?'"

The point being that if you design a system for automobility, it's impossible to not have congestion given how much space can be dedicated to roads.

Post a Comment

<< Home