Talk by Congressman Earl Blumenaur on "The Portland, Oregion urban revitalization story"

One of the presenters at the "Walkable Urban Places" conference mounted by GWU Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis and the Urban Land Institute with the sponsorship of the Venable Law Firm and LOCUS, a program of Smart Growth America was Congressman Earl Blumenaur of Portland, Oregon.

Congressman Blumenaur is known as the strongest proponent of smart growth and sustainability practices in Congress. Interestingly, he was introduced by Matthew Klein, president of the Akridge Company, one of the metropolitan area's leading developers. Apparently Mr. Klein spent a goodly amount of his early career in Portland, working on a number of transformational projects there.

Congressman Blumenaur gives a lot of presentations but mostly they are more what I call "cheerleading," designed to get people pumped up. This was the first time I've heard him present significant substance, when he talked about Portland's experience in moving revitalization forward within the city.

My notes on Rep. Blumenaur's talk

Any discussion of Portland begins with the city's "planning framework" which is shaped by Oregon's growth laws, which include an "urban growth boundary" for the Portland metropolitan area.

There is no substitute for planning. Portland was hollowing out. The city went through a number of recessions and a successful state referendum setting limits on property taxes limited the city's financial capabilities and resources. Therefore"tax increment financing" programs have been critical to the city in being able to fund and foster redevelopment and the creation of transit systems like the Portland Streetcar.

These revitalization initiatives were constructed with a high level of citizen involvement. We had citizen oversight committees on the major initiatives, they shaped the plan in places like the River District, the Pearl District and the Portland Streetcar.

We created an economic improvement district for the Pearl District and the streetcar was the single most important catalyst to moving the program forward there. The streetcar is the "Downtown Circulator" for the Pearl District and the nearby neighborhoods it serves.

But streetcars are nothing new. Streetcar transit service was the framework for integrating land use and transportation planning for decades [e.g.,, discussion of "The Transit City" era by Muller and the discussion of "The Streetcar City" by UBC professor Patrick Condon in "Why a Streetcar Is Something to Be Desired" from the Tyee). We just went back to it.

Streetcar service augments, complements our light rail and bus services. It has extended "the pedestrian experience" and maximizes the use of land, allowing for denser development.

[The Pearl District is the redevelopment of an old railyard that was north of Downtown and next to Portland's passenger train depot. Development started there with adaptive reuse of railroad buildings into housing.]

The city's agreement with the main developer required that the city make certain infrastructure investments, which was tied to phased density within the developer's projects. We started with lower numbers and were supposed to top out at 125 units/acre [Portland also has a height limit maximum, of 160 feet]. But with the streetcar and demand, projects are being developed at 200 units per acre, and the residential density supports retail and other amenties.

For example, the Pearl District started out with 8 members of the local business association and now there are more than 450.

And we've continued to extend transit, including an aerial tram connecting the River District to OHSU, extending the streetcar, and next year we'll be opening a bridge, Tilikum Crossing (rendering at left) dedicated to sustainable transportation, with light rail, streetcar and bus service, bicycle lanes and sidewalks for pedestrians, but without lanes for motor vehicles, other than emergency vehicles.

###

Building on a strong planning framework

Note that Blumenaur's work as a City Commissioner (before that he was in the State House, and he moved from the City Government to the US Congress) built on the work of others, and the planning framework that had been established in the city from 1968-1972, when the city decided to tear down the Waterfront Freeway and build a river district in its place. They followed this with a comprehensive downtown plan that prioritized transit service to the district and de-emphasized support for automobile parking. A few years later they developed and began to implement a light rail plan and service, etc.

See "A summary of my impressions of Portland, Oregon and planning" from 2005.

Portland Oregon's Downtown Plan (from material distributed for a walking tour at the National Trust for Historic Preservation national conference, 2005)

The Downtown plan, adopted in 1972, was intended to maintain and strengthen downtown's central role in the city by reinforcing its mix of uses--including office, retail, cultural, governmental and residential. The major concepts included:

1. Creating a North-South spine of high density offices served by public transit. The (bus) Transit Malls on SW 5th and 6th Avenues, completed in 1978, provides this spine and supported private office developments.

2. Creation of an East-West retail spine along Morrison Street that would lead the city back to the river. The MAX light rail line and rebuilt streets on Morrison and Yamhill implement that concept. Waterfront Park, which replaced an expressway, provides a riverfront destination.

Pioneer Courthouse Square North, MAX Blue Line, Portland, Oregon. (Note the Nordstrom's.) Photo by Adam J. Benjamin.

3. Recognition and support for the subdistricts in downtown. The Skidmore and Yamhill Historic Districts are two premier examples of those subdistricts and zoning regulations were modified to protect them and funds were invested by the public and private sectors for rehabilitation.

4. Emphasis on transit and alternative modes for downtown access and limitations on parking. The plan prohibited new parking unless associated with new development and it prohibited the demolition of historic buildings for parking lots.

5. Design regulations to promote active street level storefronts--with retail space, public lobbies, and other pedestrian features typical of historic commercial buildings.

6. Policies to maintain the historic, fine-grained street grid and blocs. Vacating streets to form larger blocks and skybridges are rare in downtown. This helps to maintain an active street life.

7. Policies and programs to protect and promote fragile uses like housing, retail and hotels through public and private investments and regulation.

____________

The plan was able to leverage the city's compact street grid of 200' by 200' blocks. In DC the typical block is about 270' by 270'. In 800 square feet, Portland yields four blocks, with 16 corners--four extra prime corner locations to sell or rent, compared to three blocks and 12 corners in the same area in Washington, DC.

Because I don't have the right kind of camera features, I didn't take many photos of large buildings in Portland, but the website Portland Ground is an excellent source for amazing photos of Portland's architecture and urban design.

Portland's Lessons:

1. Urban growth boundaries and state planning requirements are essential to keeping growth compact and centered, utilizing preexisting infrastructure, and maintaining the worth of extant land and buildings, rather than the typical metropolitan area which experiences development further and further out, and where the politics and the economics of the region tend to be disconnected from the issues and needs of the center city.

UGBs are likely the reason for the maintenance and predominance of independently-owned retail in Portland, Oregon. I intend to write about this more in-depth in another blog entry, but the short answer is that it is likely that the Portland region hasn't experienced the quadrupling of retail space over the past 40 years experienced by other regions in the United States. Thank UGBs.

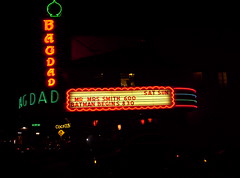

2. People with vision and commitment to more than just making money are essential to keep assets grounded in historic preservation and the other qualities that promote livability. In Portland, two brothers, the McMenamins, have bought many old theaters and school buildings and rehabilitated them into unique entertainment properties, especially with theaters. So in Portland many neighborhoods still have local theaters, although there are some chain theaters downtown. In DC, most every neighborhood theater has long ago been converted into a drugstore or similar non-"public" community-gathering-oriented use.

The McMenamin-owned Baghdad Theater is one of the centerpieces of the Hawthorne retail district, which also includes a Powell's branch open late, a Powell's specialty store, "Books for Cooks and Gardeners," the specialty food store Pastaworks, and many independent stores and restaurants.

The McMenamin-owned Baghdad Theater is one of the centerpieces of the Hawthorne retail district, which also includes a Powell's branch open late, a Powell's specialty store, "Books for Cooks and Gardeners," the specialty food store Pastaworks, and many independent stores and restaurants.Bill Naito was one of the leading developers in Portland. He renovated key properties, and focused a lot of his own time and attention on issues that were essential to the strengthening and extension of the city's livability and the public spaces. Portland renamed the riverfront parkway in his honor.

In contrast, most DC developers have been ruthless about demolishing historic buildings in Downtown in favor of superbuildings, wrecking pedestrian vitality at the street level. DC's commercial office building market thrives while the retail environment suffers. Seventh Street NW is an exception. People attribute this to the MCI Center, but I disagree, believing it is because this street is the longest stretch remaining of historic buildings, with a size and scale that is oriented to people and walking, rather than the car. This stretch, from about Pennsylvania Avenue to New York Avenue. Fortunately at the street level the new building at Gallery Place follows this pacing, and so do the stores, such as Urban Outfitters, that have located there.

Building in the Yamhill subdistrict of Downtown.

3. Continued focus on development of the core. I don't know if this is a separate entry or merely a subentry under (1) above. But the combination of urban growth boundaries, transit investments, and a focus on extending livability such as the creation and continued development of waterfront parks on both sides of the river not only keeps Portland relevant but dominant in the Portland metropolitan region as the number one place to work, live, and relax. Many Portland neighborhoods, especially those with Streetcar or Light Rail service, are experiencing a resurgence and increased demand for housing.

New park in the Pearl District, constructed as part of community amenities requirements associated with new developments.

New park in the Pearl District, constructed as part of community amenities requirements associated with new developments.This isn't to say all is well. Not every street and block in downtown Portland thrives, but there is a lot more going on that is positive rather than negative.

4. Jane Jacobs says that one of the four key factors to successful center cities is a large stock of old buildings. She said this not because she is a preservationist, but because buildings that have been paid off cost less to rent, and therefore are natural incubators of innovation. Be it retail, industrial, or service, all can be accommodated in such buildings.

160,000 s.f. abandoned Meier & Frank Warehouse in the background. (Meier & Frank was owned by May Department Stores, owners of The Hecht Company.)

But what makes this work more practically in Portland again comes down to urban growth boundaries that prevent sprawl and also prevent the construction of speculative new buildings that make obsolete otherwise perfectly usable buildings.

Because this kind of new construction doesn't happen so much in Portland's suburbs, builidngs in the center city are still valued. Because Portland was an active port and industrial center, there are many buildings, particularly in the industrial-manufacturing quarter on the east side of the river that is experiencing a great deal of renewed interest. Because of the decline in manufacturing, there is still a surfeit of buildings available.

The rents in Portland, for industrially-appropriate space (which includes software development, graphic design, and architecture) run under $20/s.f., and as I mentioned before, in many attractive retail districts, rents range from $12-$20/s.f.

By retaining loading docks, and making them part of leasable spaces, the East Bank Commerce Center (pictured at right) can attract tenants who need the convenience of in-space loading and unloading facilities.

By retaining loading docks, and making them part of leasable spaces, the East Bank Commerce Center (pictured at right) can attract tenants who need the convenience of in-space loading and unloading facilities.5. Active streets and mixed uses are maintained through most city policies. The Pearl District is a perfect example. Retaining historic buildings, their storefronts, a mix of activities and uses throughout the day and into the evening, and the pedestrian-scaled rhythm of the street makes for a lively city.

6. Transit investment is substantive and continues. Portland understands the importance of keeping the city relevant in the region by making it easier to get around. Transit services are on and part of the streets, but transit doesn't overwhelm the street, and they are designed from the outset to maintain and enhance the economic value of residential and commercial property in the areas that are serviced.

With the streetcar, north and eastbound services run on one street, while service in the other direction runs on another street. The same goes for MAX service in the Center City, trains in one direction run on Morrison Avenue, and on the other direction on Yamhill. Outside of the center city, the system runs on parallel double tracks.

Generally streetcars are intended to provide more stops and service for trips of shorter duration. Light rail is "heavier" and more expensive to build and provides fewer stops and speedier travel, and runs on the ground. Heavier rail is what in DC is the mostly underground subway. An advantage of underground service is that it's fast because it is not impeded by crossings. It's also very expensive to construct. Just to install an inline station on the extant system (New York Avenue station) cost close to $120 million.

Portland Streetcar near Portland State University. Photo: Portland Ground.

Portland Streetcar near Portland State University. Photo: Portland Ground.Streetcar Planning Goals for Portland:

-- Link neighborhoods with a convenient and attractive transportation alternative.

-- Fit the scale and traffic patterns of existing neighborhoods.

-- Provide quality service to attract new transit ridership.

-- Reduce short inner-city auto trips, parking demand, traffic congestion and air pollution.

-- Encourage development of more housing & businesses in the Central City.

These are sound planning principles for every community!

The Portland Streetcar, which is run by the city, has about 8,000 riders/daily [as of 2005, the numbers are much higher now, but the route miles served by the streetcar have been extended] , while the MAX system averages close to 100,000 daily riders, over a 44 mile system.

The thing we have to remember is that DC transit usage is far higher than most cities, including Portland, Oregon. Most of the high use bus lines in DC proper have greater ridership than the Portland Streetcar, although DC bus ridership is not higher than Portland's light rail, which is more comparable to DC's subway system.

But the WMATA subway crushes Portland's system in terms of daily ridership (our system covers more ground and more people work in Downtown DC). DC's system has over 100 miles of track and serves between 500,000 and 800,000 daily riders.

For a lot more discussion and photos of transit in Portland, check out the NYC Subway World page on Portland, as well as this section from Light Rail Now.

Labels: fixed rail transit service, transit and economic development, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

2 Comments:

Just came across a 2014 piece from Willamette Week, the alternative newsweekly for Portland, with more back story on how light rail came about:

https://www.wweek.com/portland/article-23466-feb-4-1974-portland-kills-the-mount-hood-freeway.html

1/23/2019

Wow, what an amazing information!! Thanks so much.

Post a Comment

<< Home